Defensive line to stay-at-home dad: Former Washington State’s Keith Millard embraces family life

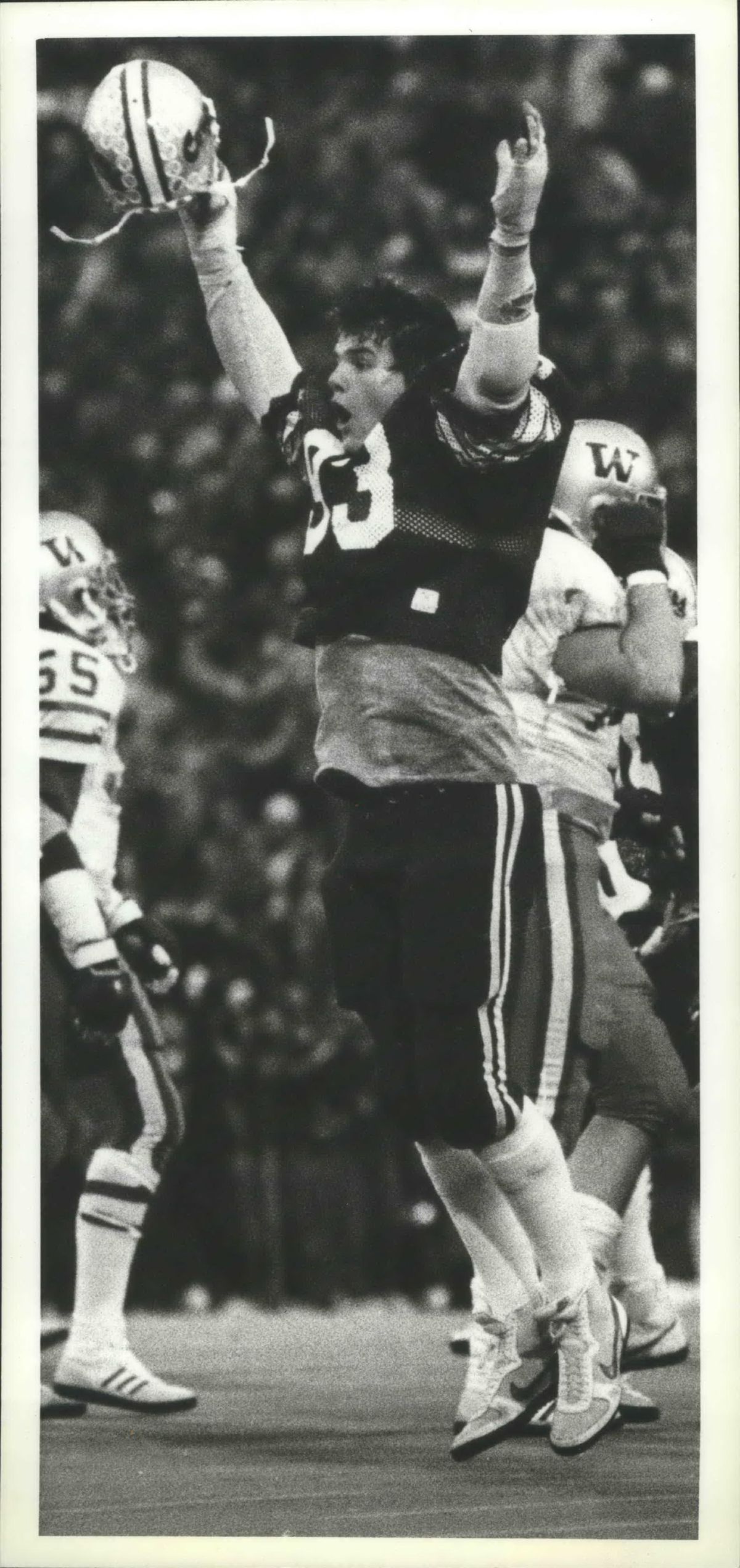

Green Bay Packers quarterback Don Majkowski gets taken down by Minnesota Vikings tackle Keith Millard for his 8th sack of the game in Minneapolis, Oct. 15, 1989. (Jim Mone / AP)

SEATTLE – Keith Millard a stay-at-home dad?

It would have been hard to picture two decades ago when Millard, the former Washington State star with the bad-boy reputation, was terrorizing NFL offenses with off-the-chart intensity as a defensive tackle for the Minnesota Vikings and was the 1989 NFL defensive player of the year.

But after decades of football, Millard, a father of six, has found happiness at home. Two of his kids are still at home in Dublin, California, and he tends to them while wife Paula works.

“The responsibilities are endless,” said Millard, who has kids ranging from 13 to 31 and two young grandsons. “It’s a seven-day-a-week job. My wife is eight years younger than me and is still finishing her career, so when I retired I took over her duties. It was an adjustment for sure. I do everything that anyone else would. I wash clothes, I cook and I try to do everything I can to keep things normal and going as smoothly as possible.”

Millard, 56, wanted it to be different for his kids than it was for him, as one of nine kids in a dysfunctional mixed family that was filled with tension.

He eventually found an outlet in football.

“I didn’t start playing football until my junior year of high school,” he said. “Nobody in my family went to college, and I never imagined I would go to college. I loved the sport, but my mom would not let me play as a kid.”

Millard played tight end for Foothill High School in Pleasanton, California, as a junior, showing good hands. He said he was 6 feet 4 and about 190 pounds, “and was always pretty good at catching the ball, and worked my way to first team.”

But things at home weren’t going well, and Millard moved in with a brother. A new football coach was hired at Foothill, and he and Millard did not get along. A few games into his senior season in 1979, Millard was kicked off the team.

“I had an attitude and I definitely contributed to it,” Millard said. “I only played in three or four games at the most my senior year, but they were really good and stood out. But when recruiters came, the coach was bad-mouthing me.”

That could have been the end of Millard’s football career. But one day a Washington State football recruiter was at his school to look at another player. One of Millard’s teachers, George Baljevich, intercepted the recruiter before he could speak to the coach.

“He told him my story and said, ‘You need to look at film of this guy,’ ” Millard said. “They brought the film to coach (Jim) Walden and everything kind of took off from there.”

Walden wanted to visit with Millard’s family, so Millard made a call to his mom and stepdad.

“I said. ‘I need to be in the house so they will think I have a normal family life,’ ” Millard said, laughing at the recollection. “So when they came, it was a little intense to say the least, but I think we pulled it off pretty well.”

Later, Millard learned that Walden had been aware of his situation.

“His mom remarried, and that did not go well with him,” said Walden, 80, who coached WSU from 1978-86, and later became a longtime analyst on WSU football radio broadcasts. “I am not going to get into all of that, but it was very disconcerting with him and his new stepfather. … There was some anger, and it took him some time to work through that.”

The move to Pullman changed everything for Millard, and he credits Walden “for saving my life.”

“It was the opportunity of a lifetime and I was taking it seriously,” Millard said. “I knew what I wanted to do, and I was going to do whatever it took to get there. Thank God we had great leaders that set great examples. And coach Walden – I can’t tell you enough about that guy.”

Still, there were pitfalls. Millard got a reputation as a bad boy. He spent 17 weeks in jail during the summer after his junior year for a case in which he was convicted of simple assault in the fourth degree.

“His reputation at Washington State far exceeds what he actually did,” Walden said. “I think people sometimes have a tendency to embellish when kids get into trouble. Keith was pretty full of himself. But he was never as much of a problem for me as a lot of people thought he was. Actually, he was pretty fun to coach. He had a little streak in him, but he was a good guy.”

Millard’s football life changed when he switched from tight end to defensive line as a sophomore.

Millard said, “I considered myself a pass-catching tight end,” but there was no need for a pass-catching tight end at Washington State, which ran the run-heavy veer offense.

At 215 pounds by then, Millard was built like a linebacker, but there was no need for another linebacker. He would need to be a defensive lineman.

“I said, ‘I will do it,’” Millard said. “The spring of next year I was moved to defensive line.”

He got himself to about 240 pounds and for the next two years he terrorized offenses, with two of the greatest seasons by a WSU defensive player.

As a junior and senior, he combined for 39 1/2 tackles for loss, fifth most in school history, and had 21 1/2 sacks, sixth in school history. He helped WSU to two consecutive victories in the Apple Cup in 1982 and 1983, and won the Morris Trophy as a senior in 1983 as the Pac-10’s top lineman.

Not bad for a converted tight end.

“Right away, some of the coaches said it was the best thing that ever happened to me,” Millard said of making the switch. “They thought I had a good future at it. That was encouraging, but I never thought more than that. Once I got into the groove and found my niche … I don’t want to sound conceited, but I was pretty much unstoppable at that point.”

To his surprise, the pro scouts were paying attention. He was drafted in the first round, No. 13 overall, by the Minnesota Vikings, and in the first round of the United States Football League, where he began his pro career.

“My thought process, even in my senior year, was all I wanted was a shot in the league and I would take it from there,” he said. “I never thought in a million years I would get drafted, let alone in the first round. That was a shock to me.”

After finishing second in the USFL in sacks with 12 in 1984, he joined the Vikings in 1985 and his career continued to ascend. He was up to 260 to 265 pounds, and among the most feared players in the league. He had no trouble getting around bigger players with his superior quickness and immense desire.

“I worked hard, was focused, studied hard and was a student of the game,” said Millard, who set the NFL record for sacks by a defensive tackle with 18 in 1989, and his record lasted almost 30 years before the Rams’ Aaron Donald broke it Sunday. “I was an absolute dedicated, hard-working, hungry, goal-oriented type of player.

“I just wanted to keep going and see how far this thing was going to take me.”

It seemed that would be the Pro Football Hall of Fame. But then, in the fourth game in 1990, he blew out his knee, including tearing his ACL, and underwent reconstructive knee surgery. He was never the same.

Millard missed the 1991 season, and then the Seahawks traded a second-round draft choice for Millard in 1992, hoping he could regain the form that made him the 1989 NFL defensive player of the year.

He was released after two games with Seattle, then suffered a broken hand with Green Bay after signing with the Packers.

“It was cool at first,” Millard said of joining the Seahawks. “But I think it was a mistake, because, No. 1, I don’t think I was as ready as I thought I was. And No. 2, I lived in Seattle in the offseason, and I had a lot of friends that were a distraction to me. And my knee was still very problematic, trying to get confidence on it. I was in the training room a lot, getting treatment on it. It was very frustrating.

“Those were some tough years for me, I’m telling you. Tough years, man, going from being at the top of my game to the rug being pulled out. I had always come back from injuries and I just couldn’t come back from this one. My thought process in the past had been I will work through it. I will work harder than anybody and do whatever it takes. But it was never right, and I could not do what I did before. Not even close.”

Millard was ready to retire but was talked into signing with the Philadelphia Eagles in 1994. He played but his heart was not in it, finishing with four sacks, including a sack against the 49ers in his final game.

“I knew I was done,” he said. “I never looked back.”

He figured he was done with football, and headed to his ranch in Arizona. But one day, the local high school football coach knocked on Millard’s door, wanting to know if Millard would help out with the defense. He did, he enjoyed it and he excelled.

A coach was born. Millard quickly worked through the ranks from college to the NFL, getting a job as the defensive line coach with the Denver Broncos in 2001. That was followed by stints as an assistant with the Oakland Raiders, the Tampa Bay Buccaneers and Tennessee Titans, with an interruption to get the first of two hip replacements at age 38.

His growing family stayed in California during his final two NFL jobs, and when the staff at Tennessee was fired in 2013, Paula had a talk with Keith.

“She said, ‘You really need to quit. You are getting old, your kids are getting older, you’re missing a lot of time with your family. You need to stop,’ ” he said. “So I did. I started getting back into my kids’ lives and feeling pretty good about it.”

Coaching was limited to helping with his kids’ teams.

“I help where I can, to be with my kids,” he said.

In addition to the hip replacements, Millard also has had a knee replacement and now needs to get his neck fused. But he doesn’t let that cut into his duties at home. It’s where he is staying, even if the football temptation never leaves for good.

“There is a huge adjustment from 14 hours every day and the pressure of the game that you get used to, then go to nothing,” he said. “It took me a couple of years to get used to it. Every year I think about getting back but reality kicks in. I can’t do it anymore.”

Watching from afar with great pride is Walden.

“He’s one of my biggest accomplishments in a sense of I’m proud of what he became because I know from where he came,” Walden said. “I know how hard the journey was. And I know what a commitment he has made over the years to get where he is and to make decisions that he’s making. I love how much he loves his family, raising them, and how much he is enjoying them. It just makes me feel that’s what coaching is all about. I am very proud of Keith Millard. Really, really proud.”