This column reflects the opinion of the writer. Learn about the differences between a news story and an opinion column.

Shawn Vestal: In a soldier’s journal, the story of war and what comes after

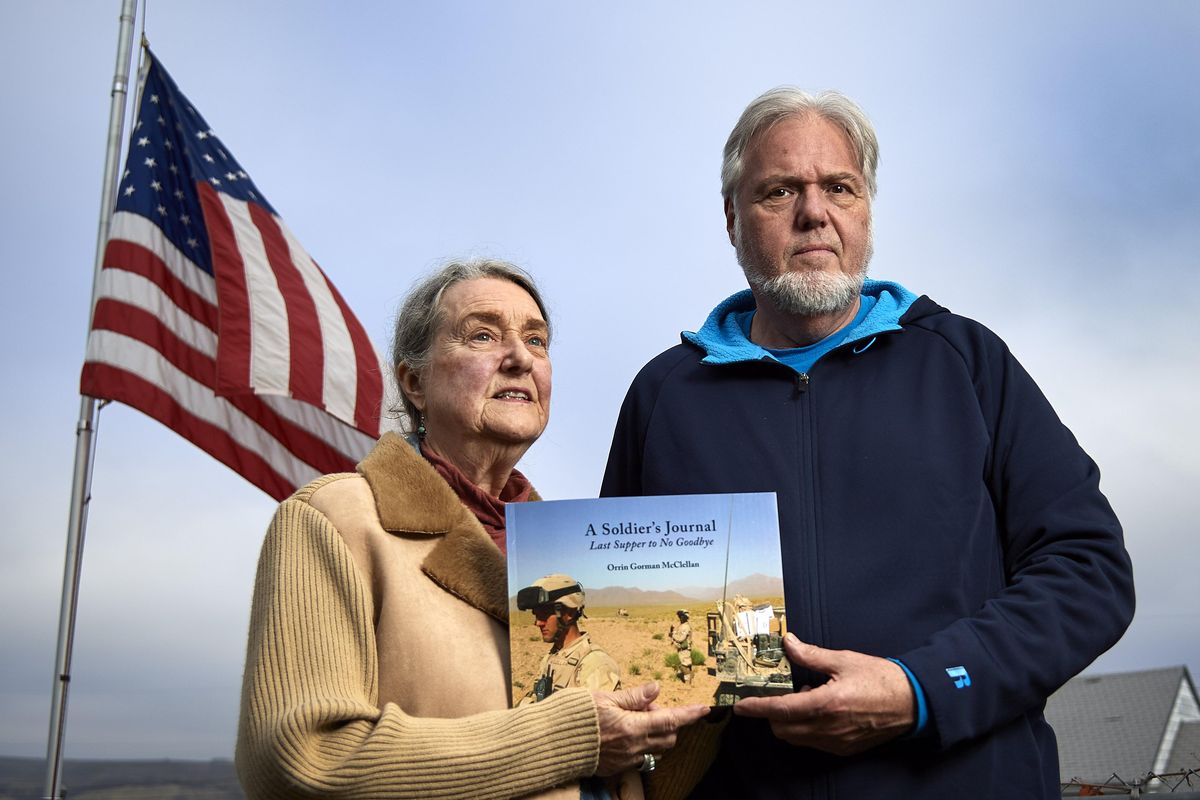

After their U.S. Army veteran son Orrin Gorman McClellan committed suicide in 2010, parents Judith Gorman and Perry McClellan worked for years to compile and publish a book of their son’s personal writings and photos documenting his war experiences in Afghanistan. (Colin Mulvany / The Spokesman-Review)Buy a print of this photo

Before he left his Whidbey Island home for Army boot camp in February 2004, Orrin Gorman McClellan wrote in his journal.

It seems like yesterday I was 10, running through the woods make-believing with my friend, not caring about anything.

While he was training in Italy to serve as a mortar man in Afghanistan and struggling as a 19-year-old newcomer to fit in with a crew of combat-hardened veterans, he wrote in his journal.

I just can’t be something I’m not … I won’t. And if the price for that is being alone, being miserable, and isolated among these people who are now my family, then so be it.

After a combat mission in May 2005, when he found himself carrying the body of one of his six fellow soldiers who died that day, he wrote in his journal.

I really don’t have anything moving to say.

nothing beautiful comes to mind.

the dead don’t look real.

they look like wax.

Orrin wrote about the dust of the desert and the emptiness of the time. He wrote about feeling an absence of purpose and an anger at meaninglessness. He wrote about dead Taliban fighters and continual casualties among his own company. He wrote about feeling dead inside and he wrote about his joy upon his honorable discharge.

i am alive!

He wrote before he left and he wrote when he returned. He wrote as he struggled with PTSD and a disability from compression injuries in his joints and back.

On April 14, 2010, he wrote:

I miss who I used to be.

No goodbye.

It was Orrin Gorman McClellan’s final journal entry.

The adversary at home

The flag outside Judith Gorman and Perry McClellan’s small Soap Lake home always flies at half-mast.

It’s there in memory of their son, Orrin, who took his own life following an extended battle with the wounds that so many warriors bring home with them: post-traumatic stress disorder, likely traumatic brain injury, hearing loss, compression injuries, a system-wide trauma through the body that he couldn’t quiet or control, and which could be triggered into flashback by traffic, by barking dogs, by fireworks.

Their flag also flies at half-mast in honor of so many others: the roughly 20 military veterans who take their lives each day, according to official counts that many believe are too low.

“I never fly my flag at full mast anymore – not until something is really changed about sending our children to war,” said Gorman, 72, on a gray recent day.

The flag flies for the same reason that Gorman and McClellan have compiled, edited and published a book of their son’s journal entries, “A Soldier’s Journal: Last Supper to No Goodbye.” The book is full of color photos of and by Orrin, and of a pared-down selection of the journal entries – which Orrin almost always wrote in a terse poetry that veers from anger to tenderness, from sadness to humor, from excitement to resignation.

The couple raised Orrin on Whidbey Island, and have moved to Soap Lake. Gorman edited the book, selecting poems and journal entries that, taken in order, tell a moving, tragic story of a young man, in his own words, engaged in a fight against the single most deadly adversary for those who serve in combat: suicide.

The suicide rate among veterans is 1.5 times higher than that among the general population, according to the most recent statistics from the Department of Veterans Affairs, and suicides have surpassed combat as the leading cause of death among soldiers deployed in the war. In 2016, the most recent year available, veterans accounted for 14 percent of all adult suicides in the country, though they account for just 8 percent of the population.

And, while the suicide rate overall declined slightly, the rate among younger veterans, ages 18 to 34, jumped 10 percent.

That report and veterans support groups nationwide have long called for a more robust array of services for veterans to help prevent suicide; the report cites some successes, but calls for more.

Orrin’s parents want the book to serve as a testament to the unseen wounds of war – to focus attention and raise money to support efforts to provide better care for the traumatized men and women who serve the country in combat conditions that can be physically and mentally ruinous. Gorman was in Spokane over the past few days for the Warriors Heart to Art retreat, an annual event in which veterans suffering from PTSD try to find healing through writing, music and other creative arts.

Orrin’s parents say the book shines a light on some of the “secrets” that a lot of combat veteran carry silently – secrets they can’t or won’t share. Breaking through that wall of silence is important, they said.

“My parents were both in the Army, and they lived with their secrets their entire lives, and neither one of them ever healed at all,” McClellan said. “My hope for the book is that it becomes a vehicle for people to discuss what they have in common and share it.”

‘Deer in the headlights’

Orrin grew up on Whidbey Island, where his parents had a home and some acreage. He was a talented, sensitive kid, who spoke Japanese and whose paintings still hang in their home.

Judith and Perry each had personal experience with warriors who returned home but didn’t really recover. For Judith – a counselor who has worked with veterans in various capacities over the years – it was her high school sweetheart, who returned from Vietnam so badly traumatized that he became an alcoholic, eventually dying in a car crash.

Orrin enlisted in the Army shortly after his 18th birthday without telling his parents. They had talked about the possibility of him entering the military – possibly as a translator – but were disappointed that he was guided toward the infantry.

He left for boot camp in February 2004, and arrived in Italy for further training several months later. He was later stationed with the 173rd Airborne, which conducted missions out of Forward Operating Base Lagman in Afghanistan. He was part of a three-man mortar team.

He struggled to get along with the older men in the unit; he communicated by instant messenger with his parents as much as he could.

In his journal, he writes of losing his friends in battle and of carrying the dead from the battlefield. He writes of tense confrontations with local villagers – and comic interactions with local villagers. He struggles on the page with the purpose and meaning of what he’s doing, and frequently questions the worth of it all.

He came home on Christmas leave for a few days at the end of 2005, and his parents saw changes in their son.

“He looked like he was startled,” Perry said.

Judith added, “Deer in the headlights.”

He returned to the war, and was honorably discharged in November 2006. The idea was to come back and go to college – he started taking some classes on Whidbey Island, then moved to Bozeman to do that at Montana State, with a childhood friend.

But he was suffering on every front. His PTSD was undiagnosed. His compression injuries in his joints and back – which would eventually be diagnosed as a 100 percent disability – put him in constant pain. He was drinking a lot and he stopped going to school, and eventually Perry drove over to Bozeman and brought his son home to Whidbey Island.

One day, Judith noted that Orrin was cleaning his rifle, checking his gear, and packing his truck as though leaving for a long trip.

“I said, ‘What are you doing?’ ” she said. “He said, ‘I’m going on a mission.’

“He thought he was in Afghanistan.”

In a runaway car

It was a slow road to getting treatment. Orrin was initially resistant, and it took an arrest while he was drinking and being combative with police – “One of those ‘Kill me, kill me’ things,” Judith says – to help move him toward getting help at the VA center in Seattle.

The visits themselves were traumatizing – the crowds, the traffic, the noise. Just getting there to get help was painful, Judith said. A VA representative had once suggested that he move to a homeless shelter near the center, in order to avoid having to make the trips.

In 2008, Orrin was hospitalized three times, twice in Seattle and once in Roseburg, Oregon, to deal with his heavy drinking and then his PTSD.

But his parents thought he was showing signs of improvement. He and his fiancée had their own place and were planning to marry. He was in contact with fellow veterans around the country who were battling PTSD themselves, and he had a lot of “clear times,” Judith said.

But there was also the continual risk of tension from PTSD – which he once described as akin to operating a car with the gas and brake both floored.

Both he and his parents were well aware of the realities of suicides among veterans.

“He promised me he wouldn’t kill himself, and I believed him,” Judith said.

One day in April 2010, Orrin was preparing to travel to Seattle the following day for a VA appointment. He was at home with his fiancée, drinking and playing video games into the early evening.

His parents believe he was having a flashback during what happened next. Stressed out and drinking, a tense Orrin might well have been further triggered, they say, by fireworks in the area and the arrival of a neighbor with a loud, barking dog.

“It was just overwhelming,” Perry said, the pain in his voice still palpable a decade later. “It was just too much.”

Orrin retrieved his guns from a safe, and fired it once into the ground. The neighbor left, and alerted police. Orrin took his own life before they arrived.

A story of thousands

It’s truly an epidemic. What happened to Orrin happens every day, all around us, to the people we have sent off to do traumatizing work on our behalf while so many of us pay scant attention to the consequences.

“This is a river that just keeps flowing,” Perry said. “You’re more likely to commit suicide than die in military action – the same people.”

He and Judith hope “A Soldier’s Journal” can help provoke more community conversations and understanding – and especially a realization among civilians that our means of caring for the young men and women who return from the military are insufficient.

Civilians, Judith insists, have to do a better job of helping veterans carry their burdens and of understanding just what those burdens are. She began working on Orrin’s story before he died, because he wanted that message to get to people but wasn’t able to sort and edit his own work.

His story is absolutely gripping and absolutely heartbreaking. Reading it takes you into his experience in a powerful way, unlike any other kind of narrative of war. And yet for both his parents and for him, it’s more than just the tragic story of one young man.

It’s the story of thousands and thousands.

“This is not about Orrin,” Judith said, “and it never was about Orrin – even from Orrin’s perspective.”