50 years on, remembering Spokane’s Natatorium Park

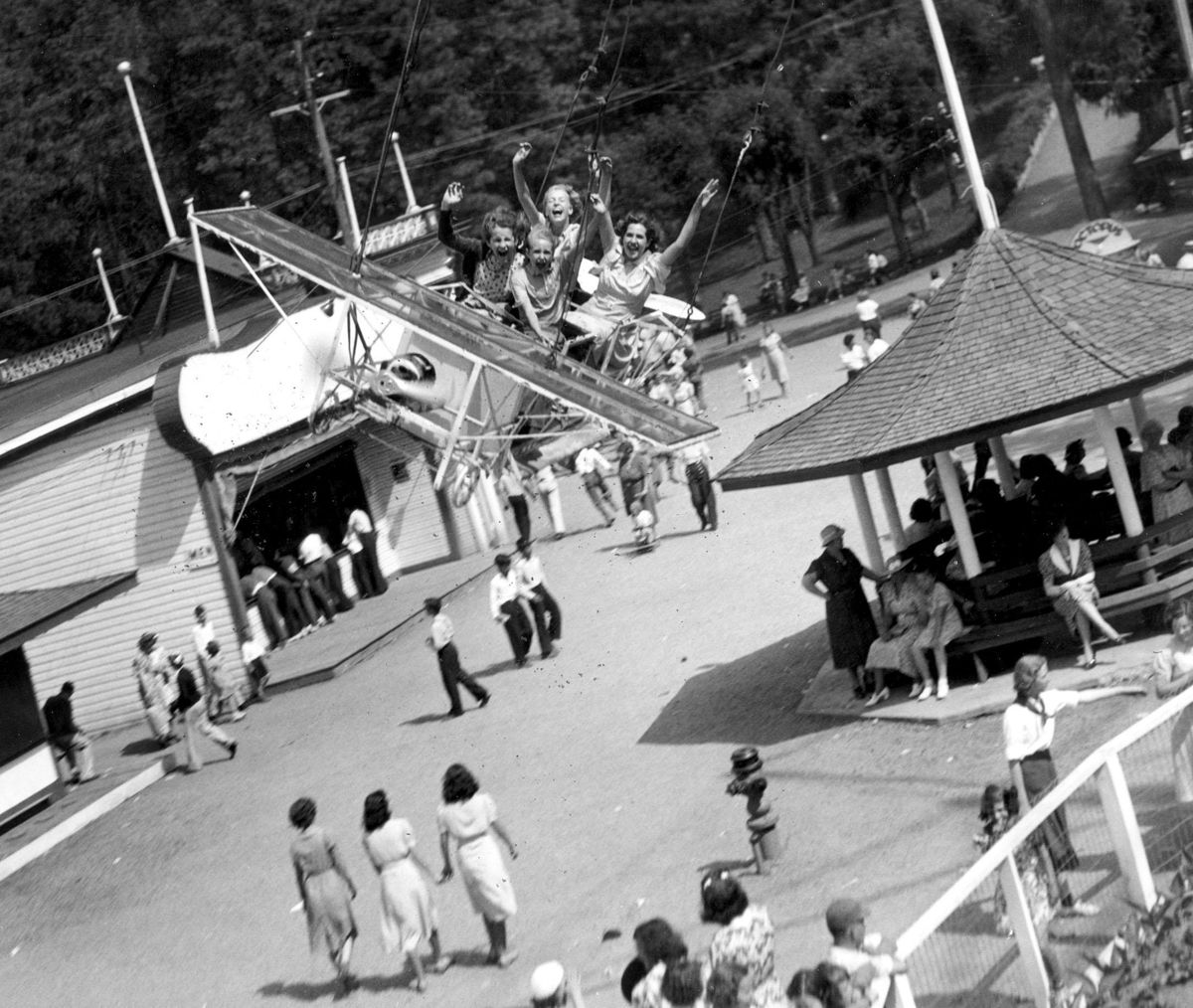

In 1941 the amusement rides at Natatorium Park were in full swing. The park, which opened in 1893, was originally known as Twickenham Park, and was operated by Spokane United Railways until 1929 when it was sold to Louis Vogel. The park closed in 1968. (PHOTO ARCHIVE / SR)

Like the stone lions in front of the old First National Bank building, or the golden statue that sat astride the long gone Auditorium, or the smoke-free days of August, Spokane’s Natatorium Park is just a memory.

How many can say they rode the Dragon slide, magic carpet, chute-the-chutes, Custer cars, Dodgem cars or whirl-o-plane? Or saw Babe Ruth play an exhibition game in 1924? Or danced to Benny Goodman, or Bob Wills and his Texas Playboys into the night?

How many know that the quiet San Souci West retirement community sits on land that was the most raucous place to bring a date on Saturday night for decades, before the automobile, television or “some other recreational disease” killed off what had been the center of Spokane’s rollicking, frolicking life?

Not many. But we all have heard the name Nat Park, and one of its central features – the Looff Carrousel – still sits center in this city, both in spirit and geography.

This year marks the 50th anniversary since the park closed, and the Northwest Museum of Arts and Culture is throwing a gala tonight to commemorate the jubilee. Dear Old Nat’s Big Band Bash, as it’s billed, will feature an eight-piece jazz band and whiskey sour snow cones, and the museum is encouraging folks to “dress to impress in Big Band era attire true to Nat Park’s thriving decades of the 1930s and 1940s.”

Despite the passage of time, the old park lives strong in Spokane lore. Its glory days do, anyway. And even though its demise was not as brutal as that of the Manito Park Zoo, it’s a sad tale nonetheless, if just for the longing it stirs in some hearts.

Bolster’s big dream

Part of that longing surely stems from the park’s connections to old Spokane.

The foundations of Nat Park began in 1889 with a man named Herbert Bolster. Bolster had big plans for a city called Twickenham on a forested plateau overlooking downtown, which is now home to Spokane Falls Community College.

His suburban idea was ahead of its time, but Bolster believed in it. He platted Twickenham for 12 blocks of housing, built a baseball park and erected a wood and iron double-decker bridge to span the Spokane River at the west end of Boone. The top deck supported his cable cars; the bottom a roadway for teamsters, horses and carriages. On one side of the bridge was the city of Twickenham. On the other, the future site of Nat.

Bolster’s plan never took off, and he likely went bankrupt after Spokane burned in 1889. The cable car line remained.

On May 4, 1892, a short-lived precursor to Nat Park opened. It was run by “Eggert and Stege,” according to the Spokane Daily Chronicle, and featured “Professor Hoppe’s 40-piece band and the Tyrolean troupe.”

In 1893, the Spokane Street Railroad Co., part of Washington Water Power Co., purchased what were Bolster’s 51 acres, bridge and his cable car route. Seeking revenue, the company built an “end of the line” park in the spirit of New York’s Coney Island.

On July 15, 1893, the Chronicle reported the opening of the “Twickenham Natatorium,” noting that a natatorium is a building that houses a swimming pool.

“The water will be brought to a temperature of 75° Fah. An orchestra concert will dispense music at the Nataotrium until 9 o’clock p.m., when dancing will begin at the pavilion. The swimming races will commence with the 100-yard race, and the boys’ 50-yard race,” the article announced.

It was an immediate hit – with soldiers from the nearby Fort George Wright, with kids, with adults.

The power and streetcar company, keeping an eye on the bottom line, threw some cold water on the enterprise soon enough.

In 1913, the company said it wanted to sell the park, according to an article in the Chronicle.

“The park has been operated strictly as a traffic producer,” the streetcar company’s president, D. L. Huntington, told the paper. “Apparently it has outlived the purpose for which it was built and has been operated and as soon as the real estate situation here justifies we will plat it and place it on the market.”

In other words, the park only existed to get people to ride the streetcar. The land at the end, where the park stood, would be sold off for a profit.

Growing with the city

Huntington’s warning wasn’t to be. Not yet.

The decades would see growth and transformation. Entertainment included amusement park rides, swimming, baseball games, picnics, big band concerts and the Looff Carrousel. Jack Dempsey boxed there. Satchel Paige pitched there. Tommy Dorsey tromboned there.

In 1914, a new automobile entrance to the park was built, with a graded road down the hill. The work unearthed a 16-ton granite slab, which was quickly turned into the “giants’ table” attraction.

In 1915, orange and lemon trees were in bloom at the park, “successful experiments in a small way to demonstrate Spokane’s mild climate.” A nearby grapefruit tree was in “fine, healthy condition. Four banana plants, set out this spring near the dance pavilion parking, are thriving and now stand fully six feet in height, with wide, healthy leaves and stalks,” the Chronicle said.

In 1919, motion pictures were considered for the park.

“If I can get a shadow box I shall put in motion pictures at the park for the season,” said the manager of the Auditorium Theater, Charles York.

The years passed, and the people of Spokane surely took it for granted that the park would always be there. It had survived from the early days of the city, made it through World Wars and the Great Depression.

The park had even outlived the original reason for its existence: the streetcar. On Aug. 31, 1936, before a crowd of 10,000 people on Summit Boulevard overlooking Nat Park, hay bales were piled inside streetcar No. 202 and it was lit on fire. The streetcar, which reportedly had logged more than 1.6 million miles during its 26 years of service, was the last of its kind. Its burning turned the page to today’s auto-centric world.

The park lived on.

The 1955 world’s Roleo championship took place at Nat Park, making Spokane the largest city to host the log-rolling competition where two contestants stand on a log and try to knock the other off.

In 1959, The Spokesman-Review wrote an article commemorating the 50th birthday for the “gayest nags in town:” the horses of the Looff Carrousel.

The ride was built in 1909 by Charles Looff as a gift to his daughter, Emma Vogel, and her new husband, Louis Vogel, for their wedding. The attraction was immediately placed at Nat Park, and began operating on July 18, 1909. Vogel operated the ride for 20 years, until 1929, when he bought the park from the power company.

Vogel ran the park through its heyday, but it was his son, Lloyd, who would finally realize the warning given in 1913 by Huntington.

In 1962, the park was no longer profitable enough for Lloyd Vogel, and he sold it to the El Katif Shriners. The park closed, only to be reopened in 1964 following some refurbishment and repainting. It wasn’t to last.

Nat Park fades away

The last year of operation for the park was 1967, but it wasn’t until spring of 1968 that the news became known: El Katif said the park site would become San Souci West, a “de luxe mobile home retirement community” that would open in the fall.

The Spokesman-Review soon wrote an obituary for the park, headlined, “Nat Park, 75, Fades Away.”

“Natatorium Park, 75, a longtime resident of Spokane, has died,” it read, noting that “time ran out for the park,” a victim of “‘TV-itis’ or some other recreational disease.”

Not to be outdone, the Chronicle wrote its own obit, which tried to surmise the reason for the park’s demise. It noted that servicemen from Fort George Wright used to hike “across the footbridge near the plunge, later the seal tank, to admire and possibly date the girls.” Young people who couldn’t afford gas would go there for low cost entertainment, it said, “where the big name bands played on Friday and Saturday nights and where the old street cars clanged their way down the grade off Boone into the special Nat ‘car shed.’”

The message was clear: The times had changed.

The rides began to get dismantled or sold off to other amusement parks, articles noted but gave little detail.

A rocket that was a ride at the park was relocated to the playground of Shoe House Nursery on North Maple Street and set on springs. The school site is now home to the Salish School of Spokane, but the rocket is gone.

Of course, the Looff Carrousel is still around, but its continued existence in Spokane was far from assured at the time.

Lloyd Vogel, who had taken over the park from his father, died in 1965. As such, Bill Oliver, the Natatorium Park handyman and electrician, inherited the ride and he wanted the Carrousel to remain in Spokane, according to a 1996 Spokesman-Review article.

He offered to sell it to the county for $40,000. “Naw,” Oliver was told. “We can buy a new one for that price.”

He turned to Spokane Parks and Recreation Director Bill Fearn, who convinced the park board to raise the money, and then some, to save the ride and give it a new home. Not everyone was on board with the idea – such figures no longer needed to be carved out of Chinese elm and balsam by hand but could be mass produced out of plastic – and they deemed the purchase “Fearn’s Folly.”

No one calls it a folly anymore. After years of being housed in the Bavarian beer garden from Expo ’74, this year saw the completion of a $7 million glass rotunda to house the refurbished ride, which still has its 54 horses, two Chinese Dragon chairs, a giraffe, a tiger and a go-round version of ring-toss.

Children still ride it, 107 years after the first children rode it, making those memories that very well may outlive the Looff Carrousel. Maybe, but probably not.