The science behind ‘the munchies’: WSU researcher aims to help cancer, anorexia patients with pot

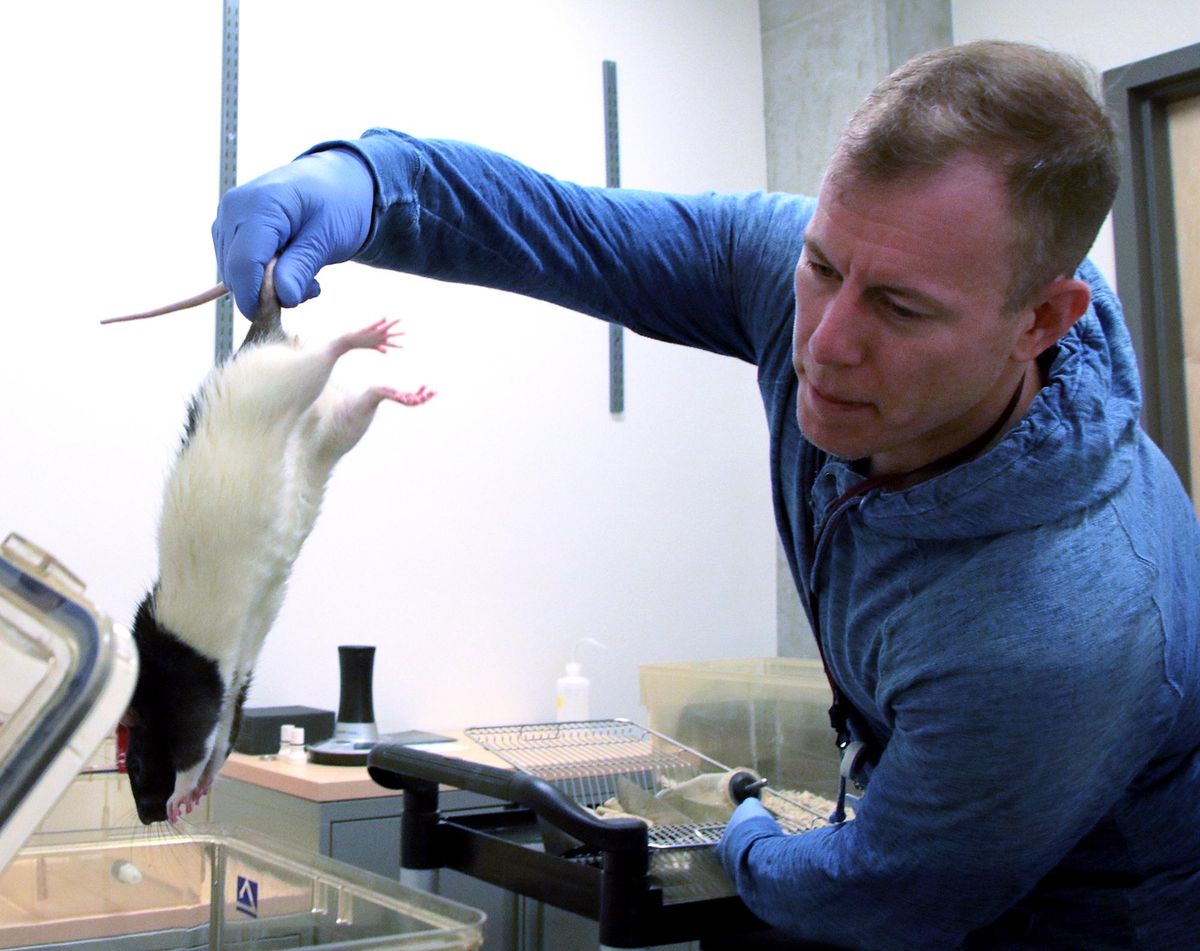

WSU researcher Jon Davis drops a rat into a tank, where he will “hotbox” it to study the effects of cannabis on feeding behavior. (Cody Cottier / Cody Cottier/For The Spokesman-Review)

The rodent peered through half-squinted eyes at the world beyond its smoke-filled plastic chamber this week, a test that subject researchers in Pullman hope will help them kickstart the appetites of chronically ill people.

“That’s what I call a ‘high’ rat,” said Jon Davis, an assistant professor of neuroscience at Washington State University. “Wouldn’t you agree? When I saw that for the first time, I was like, ‘OK, this works.’ ”

The “munchies” have been the butt of jokes in stoner movies and in the marijuana counterculture for decades, fueled by anecdotal evidence that a joint will cause the smoker to reach for another bag of potato chips or junk food. Davis, and a team of students at WSU, will present findings this summer seeking a scientific explanation for the phenomenon. The goal is to combat the malnutrition experienced by up to 85 percent of cancer patients, according to the National Cancer Institute, who are nauseated by chemotherapy drugs and the effect of the illness on their bodies.

To do that, Davis and his team had to “hotbox” some rats, including this roughly 6-month-old Long Evans lab rat that had settled in the rear of a specially designed vaporization chamber. The term refers to a group of smokers lighting up in an enclosed area that allows the accumulated smoke to linger, leading to a communal high from the drug.

“That’s probably the most accurate you could say for what’s happening,” Davis said.

The marijuana, which comes in the form of ground plant matter and not the sticky buds packaged for sale in stores, is vaporized and fed to a chamber that traps the wisps of smoke. Researchers control the temperature and airflow in the chamber while the rats are present, and then observe their eating habits for hours after they’ve been exposed to the drug.

Davis’ team, which includes graduate student Pique Choi and honors student JoAnne Kunze, found results supporting the munchies theory. After a period of about two hours, rats that had been exposed to marijuana began eating more frequently than those that hadn’t.

The results weren’t shocking, but Davis wanted to know why.

His prior work, at the University of Cincinnati, led Davis to seek levels of a naturally occurring substance in the subject called “ghrelin” that signals to the brain the need to eat. What was occurring in the guts of the rats exposed to smoke was similar to humans who’d been food-deprived for several hours: Their levels of ghrelin were rising, signaling to the brain that it was time to chow down.

“We don’t know of any other drugs of abuse that do that,” said Davis. There are synthetic forms of ghrelin, but they haven’t been approved for human use yet, meaning marijuana could provide a less invasive, more cheaply available substitute.

While the rats exposed to marijuana ate more frequently, they didn’t overeat. After four hours, rats that hadn’t been exposed to the drug resumed their normal eating and caught up to the amounts chomped by their intoxicated counterparts.

It was important for Davis to obtain marijuana in its typically ingested form, rather than a pure form of THC, the psychoactive element in marijuana. He wanted to make sure the results have wide practical implications.

“There have been some very good studies with THC, but people don’t use THC,” Davis said. “You don’t inject THC in your arm.”

His efforts to secure the drug for his trials illustrate the barriers to research of cannabis that remain in place, despite Washington and several other states legalizing cultivation and sale. Under federal law, marijuana remains in a category with heroin and cocaine that are strictly controlled for scientific testing, in addition to harsher penalties for criminal activity.

Davis, whose background is in the transmission of feeding messages between the stomach and regions of the brain, built the chamber with some start-up grant funds and completed the lengthy process to obtain a federal license to obtain research-grade marijuana from a single location at the University of Mississippi. The marijuana arrives in Pullman in a large Ziploc bag marked with a warning that the drug “is not for human use.” Davis just pays shipping costs.

The potency of THC is about 9 percent, well below levels found in marijuana that is available for purchase in any one of the 30-plus retailers around Spokane County.

His research is now part of an initiative at WSU to study cannabis across a range of scholarly disciplines, including sociology, psychology, advertising and nursing, all of it funded at least in part by the taxes paid by customers at any of the state’s hundreds of retail marijuana outlets established by a state initiative in 2012.

Those efforts have been partially hamstrung by widespread demand for state excise tax dollars, which totaled nearly $315 million statewide last year, according to the state’s Liquor and Cannabis Board. Michael McDonell, chair of the university’s Committee on Cannabis Research and Outreach, said investigators at the school are grateful for the $276,000 they received from the state during this budget cycle for research. But it’s less than one-fifth of the amount that was promised for research when the recreational market was approved by voters six years ago, he said.

“All groups, all the parties involved, have received much less money than we were supposed to,” McDonnell said. The University of Washington will get $454,000 over the next two years for similar studies, according to the Liquor and Cannabis Board. Other monies are divided between various state agencies to fund health care costs, drug abuse education and youth drug prevention programs.

About $200 million more will go into the state’s general fund, as Washington struggles with a Supreme Court mandate to fund public education.

Davis and McDonell envision a future where researchers will be able to purchase their products directly from either growers or retailers in Washington state. But for now such a system prompts fears of federal reprisals against the university or research subjects. This week, WSU researchers working to create a test to detect marijuana intoxication announced they’d be halting a portion of the study over fears the research conflicts with the directives of U.S. Attorney General Jeff Sessions and President Donald Trump on marijuana.

McDonell said his committee’s research would continue, because it does not involve human consumption of marijuana and all researchers have a federal license, like Davis’. But the effect could be chilling on the team’s planned future projects.

“There’s a lot of important research we’d like to do with humans,” McDonell said.

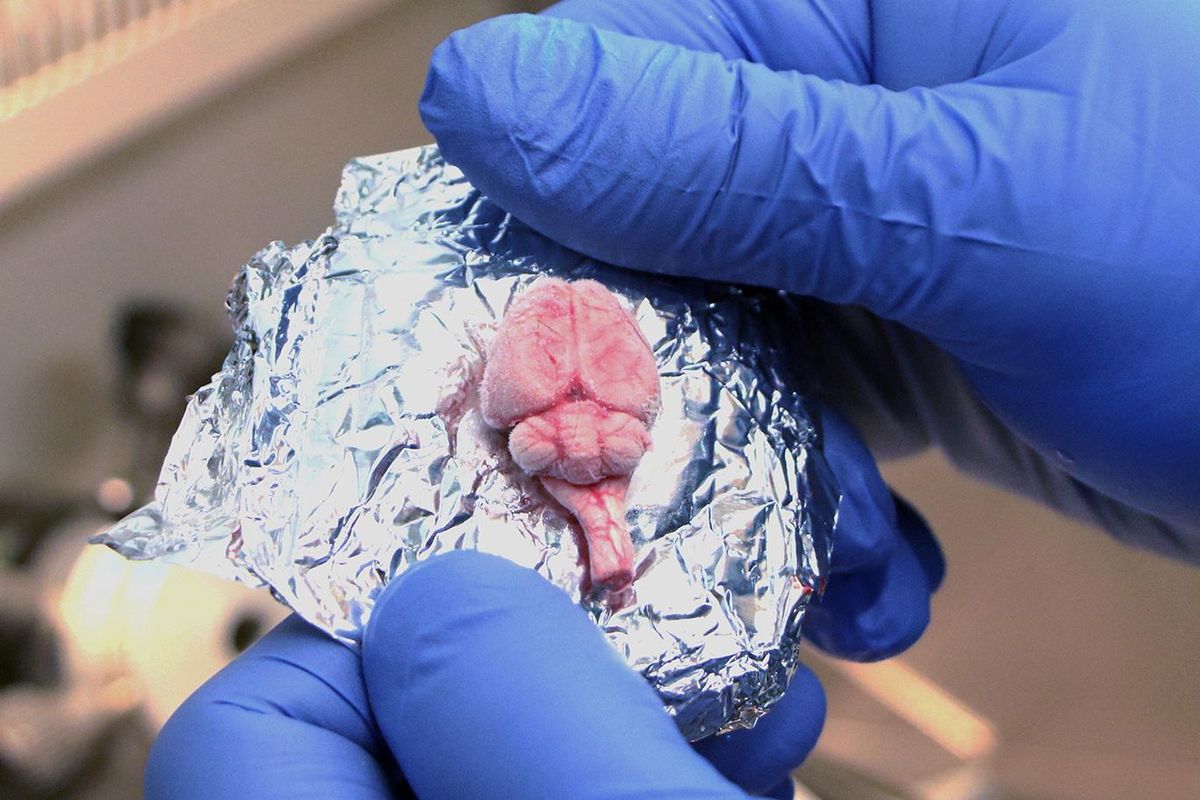

Davis and his students are putting the finishing touches on their study, including examining the brains of the rats exposed to marijuana for any genetic changes. He hopes the research will catch the eye of other scientists in a field that is lacking the academic rigor that could help patients and sellers alike.

“That’s the message I would want to convey, is that No. 1, at the federal government level, medical marijuana does have a purpose,” he said. “And here’s a way we can test it.”

Editor’s note: This story was changed on Friday, April 27, 2018 to clarify information about WSU research working to find a test to detect marijuana intoxication. The university has suspended human research as part of the research, but a study examining a tongue swab is continuing.