Lessons from the past: A Spokane teacher’s journey from trauma to mentorship

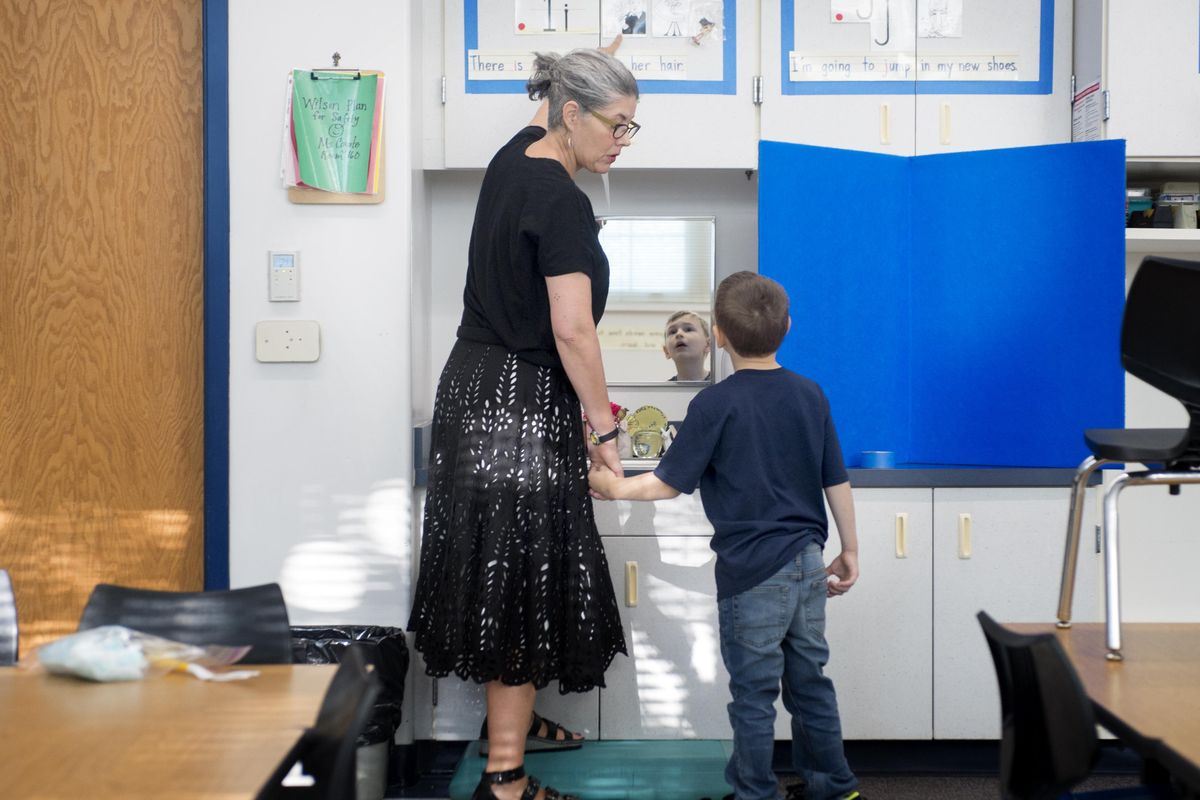

In Elizabeth Coyote’s kindergarten classroom, there is an aged photo hanging from the side of her desk.

It’s a picture of a fourth- and fifth-grade class from 1969. Standing in the second row is a dark-haired girl in a blue dress with a shy smile – Elizabeth Coyote herself. In the third row stands a clean-cut man with a decisive hair-part, large ears and a tweed jacket. Mr. Spinney.

That man, Coyote said, saved her life.

“I was taking a baseball bat to kids’ heads,” Coyote said, sitting in her classroom at Wilson Elementary a week before school started. “I was bringing the violence from my home to the classroom.”

Mr. Spinney’s classroom gave the shy, scared girl a daily respite from the violence and insecurity of her home, she said, and ultimately put her on the path to become a teacher.

So, as school starts this fall for more than 30,000 children in Spokane, Coyote hopes to pass along the support and kindness she received as a child.

“(Mr. Spinney) is the first man in my life who wore a tie,” she said, pointing to the old photo. “He was very gentle, with his words and with his mannerisms.”

Coyote grew up in Tacoma and attended Midland Elementary School. She lived across the street from the school.

Her father, an alcoholic pipefitter, was often unemployed during economic downturns. Her mother, a stay-at-home mom, suffered from postpartum depression. She had six children. She abused prescription pills.

“I remember thinking as a young kid, my dad doesn’t know how to be a dad,” Coyote said.

Her home was violent. She was beaten and emotionally abused, as were her brothers and sisters. She remembers watching her father hit her younger brother.

“It was harder to watch him being beat than for me to be slapped or chased down the hallway and my head shoved in a wall,” she said.

So, every day as she walked the short distance from her house to school, she carried those hidden experiences along.

“Things are seldom as they seem,” she said. “We probably looked like a functional family because we were – quote unquote – ‘functioning.’ ”

The dysfunction showed in school. Coyote was violent. Disengaged. Defiant. Her handwriting was tiny – letters crammed together in a nearly indecipherable jumble. It was, she said, a glimpse into her home life and internal state. By the beginning of her fourth-grade year, she was already known as a “bad kid.”

So, when she walked into Mr. Spinney’s classroom, she decided she was going to be good.

She wasn’t. She continued to act up. Her home life continued to be violent.

However, one thing changed.

“He was like no other teacher I’d had at that point,” she said. “Mr. Spinney, he never mistook me for my behavior.”

That didn’t mean he let her get away with things. He held her accountable. But – and Coyote said this was key – he showed her he cared.

“There is nothing more powerful than looking a kid in the eye and letting them know: ‘I see you and I’m delighting in you and you are wonderful,’ ” she said.

He cared so much about her, Coyote said, that he refused to let her be a bad kid.

“The very best teachers do this,” she said. “They have high affection and high expectation.”

Coyote didn’t know it then, but the two years she spent in Mr. Spinney’s class changed her life. He showed her that she was smart. His consistent kindness and firm boundaries helped her learn to trust adults. And his unwavering support gave her the strength to start the long process of overcoming her home life.

And, ultimately, his example, and that of other teachers she had, convinced her to be a teacher.

“I knew I wanted to be a teacher really early because it was just so impactful to me,” she said.

That’s not an uncommon motivation, said Kent Hoffman, a Spokane psychotherapist who works with homeless parents and children.

“Many of us go into the helping professions because we’ve been helped ourselves,” he said.

In his case, Hoffman started his career partly because of the influences of his fifth- and 10th-grade teachers, he said. One person can alter a child’s entire life, he said. It can explain why in some families a child will grow up to be a well-adjusted adult while their siblings don’t.

“The bottom line is they had one person who came through for them,” he said. “(Coyote’s) experience is very common.”

These adult role models are especially important for children under the age of 11, Hoffman said.

Children and teenagers with mentors do better academically and socially, according to a five-year study that tracked about 1,000 children in the Canadian Big Brother Big Sister Organization. Participants in the study reported more self-confidence. Girls who had mentors were two-and-a-half times more likely to report academic confidence.

Now, as school starts in Spokane, Coyote wants to be that person for her kindergarten class. Every day, she said, she sees kids acting in ways she used to act. Violent. Oppositional. Nonresponsive.

And she’s seen an increase in the sorts of behaviors she believes are indications of trauma. She blames this increase partially on growing economic insecurity and fractured families.

“We have people who are living on the edge, economically,” she said. “And the children are the most vulnerable in that situation.”

So, she said, she’ll emulate Mr. Spinney, who died seven years ago. She will be a kind, firm presence in her students’ lives. She will try to guide them forward, out of whatever traumatic situation they may be in.

And she’ll recall the time, decades back, when a teacher threw a lifeline to a scared little girl.