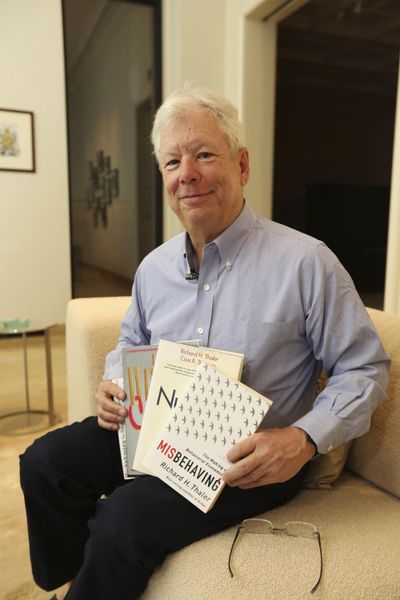

Richard Thaler wins Nobel for work in behavioral economics

STOCKHOLM – The Nobel prize in economics was awarded Monday to Richard Thaler of the University of Chicago for research showing how people’s choices on economic matters – whether on savings or game shows like “Deal or No Deal” – are not always rational.

Thaler won the $1.1-million prize for “understanding the psychology of economics,” Swedish Academy of Sciences secretary Goran Hansson said Monday.

Thaler is considered a founding father of behavioral economics, a field that shows that far from being the rational decision-makers described in economic theory, people often make choices that don’t serve their best interests. That could include, for example, refusing to cut their losses when their investments plunge in value or making big bets at the casino because they are convinced their hot streak will continue.

The illogical behavior has economic consequences: People spend more than they should and don’t save enough for retirement. They make investments – in houses in the mid-2000s, for instance – when prices are already dangerously high.

The Nobel committee said Thaler has provided a “more realistic analysis of how people think and behave when making economic decisions.”

Asked by phone at a news conference what he planned to do with his prize money, Thaler joked that he intended to spend it “as irrationally as possible.” `

In an interview later with the Associated Press, Thaler offered a deeper response that drew on the philosophy of his work:

“In traditional economic theory, it’s a silly question. And the reason is that money doesn’t come with labels. So once that money is in my bank, how do I know whether that fancy bottle of wine I’m buying (is being paid for by) Nobel money or some other kind of money? The serious answer to the question is that I plan to spend some of it on having fun and give the rest away to the neediest causes I can find.”

In 2015, Thaler provided a cameo alongside pop star Selena Gomez in the film “The Big Short,” about the global financial crisis. In the scene, Thaler explains the “hot hand fallacy,” in which people think whatever’s happening now is going to continue to happen into the future.

Asked at the news conference Monday if he thought this observation applied to the U.S president, who had some success as a business executive before entering politics, he said: “As to President Trump, I think he would do well to watch that movie.”

In 2008, Thaler co-wrote a paper examining the choices contestants face in games such as the TV show “Deal or No Deal,” including about how early outcomes affect decisions later in the game. In the paper, Thaler and the authors find that contestants become bolder in their choices when their initial expectations of how much they would win are shattered, whether by big losses or big gains.

Peter Gardenfors, a member of the prize committee, said that one of the practical applications of Thaler’s work was development of the “save more tomorrow” strategy for retirement-savings accounts. Under that model, many employees who resist immediately raising the portion of their salary put into retirement accounts will agree to raise their contributions in the following year and usually continue with the higher level.

Thaler’s contributions include studying the “limited rationality” trait that includes behavior such as the unwillingness to pay off high-interest credit card debt from a low-interest savings account. He also has studied lack of self-control as it relates to economics.

“One thing that we all recognize is that we have a little angel on our left side of our shoulder and the devil on our right side of our shoulder, and the devil wants us to have pleasure instantly whilst the angel wants us to plan in a responsible and far-sighted way,” prize committee member Peter Fredriksson told The Associated Press.

Thaler is not the first behavioral economist to win the Nobel. In 2002, the award went to Israeli-American psychologist Daniel Kahneman who used psychological insights to study how people make economic decisions.

The economics prize is something of an outlier – Alfred Nobel’s will didn’t call for its establishment and it honors a science that many doubt is a science at all.

The Sveriges Riksbank (Swedish National Bank) Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel was first awarded in 1969, nearly seven decades after the series of prestigious prizes that Nobel called for. Despite its provenance and carefully laborious name, it is broadly considered an equal to the other Nobel and the winner attends the famed presentation banquet.