The North Riverbank Urban Design Plan: a 1982 look into the future of Kendall Yards

As the blush of Expo wore off, along with the cloth covering of the U.S. Pavilion, urban planners were at a loss. The fair had done the work to deliver a blank canvas for downtown growth.

Lost in the redevelopment was the river’s north bank, so planners put together the North Riverbank Urban Design Plan in 1982.

Again, no notion was too big for this “workbook of ideas,” as they called the plan. Still, planners assured city leaders that the plan mainly revolved “around rezoning and height restrictions.”

But like many things sprung from the 1970s, the plan aimed cosmically high. It invoked Barry Commoner, a scientist and founder of the modern environmental movement, and grafted his ideas of ecology onto urban planning.

“Everything is connected with everything else,” the plan said, quoting Commoner’s first rule of ecology. But the plan took it farther: “The city (is) like the universe.”

Despite such lofty sentiments, the plan has very earthbound ambitions. It supports pedestrians and bicyclists, parks and open space, a dense and central retail district, planting trees along major roads, supporting transit and many other themes that today’s planners at Spokane City Hall still trumpet.

Except one: density.

While density may be lurking in the heart of new plans in the city, officials are wary to use the word ‘density.’

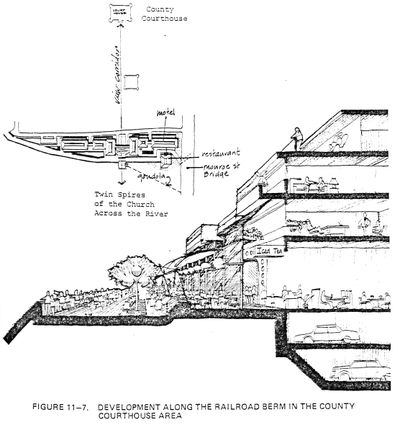

Not so in 1982. Just look at this plan’s conception for what is now Kendall Yards. A mixed-use building stuffed with residential, office and retail units, a wide pedestrian esplanade butting up against the building, which just so happens to have two stories of underground parking.

Unlike today’s catchphrase of “live-work-play,” this plan had people living, working, playing, walking, parking, eating, shopping and hanging out enjoying the view.