Former Seattle Seahawks star Curt Warner opens up about twin sons’ battle with autism

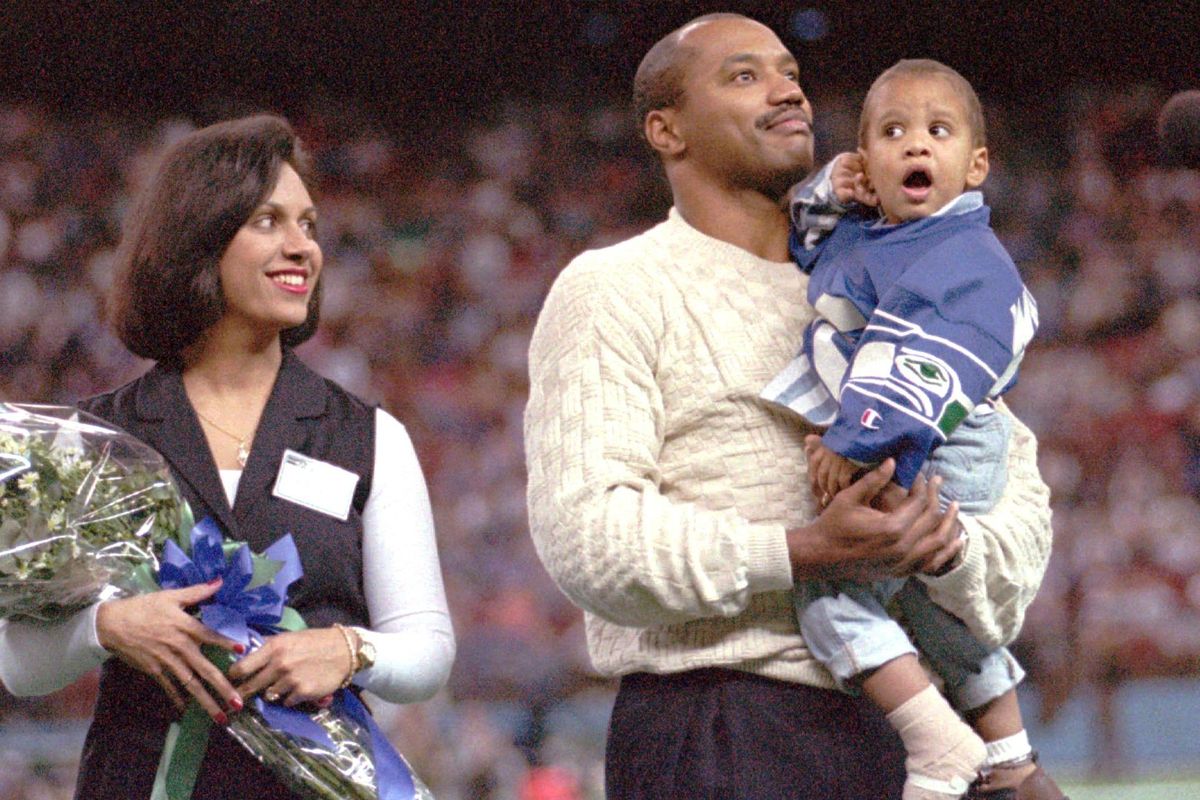

Running back Curt Warner, his wife Ana and 2-year-old son Jonathan take part in a Seahawks’ Ring of Honor ceremony for Warner in November, 1994. In 2008, Jonathan was credited with saving family members’ lives from a house fire that was started by one of his younger autistic brothers. (BARRY SWEET / Associated Press)

Curt Warner dodged the questions for years.

How come we never see you? Is something wrong?

People want answers when someone such as Warner, a famed and beloved Seattle Seahawks star, withdraws from the public eye for more than 20 years. Warner and his wife, Ana, never knew what to tell people.

If they detailed the around-the-clock challenges of raising their twin autistic sons, people might think they were complaining, or were ungrateful for lives that included so many gifts. They certainly didn’t want to give that impression.

“People would asked me why I didn’t do things in public or make appearances,” Curt said. “I just always knew that (Ana) needed my help here, at home, with the family. That was always my No. 1 priority.”

Warner famously recovered from a career-threatening knee reconstruction early in his career as an All-Pro running back for the Seahawks in the 1980s. So he understood pain, and knew what it took to reach deep inside for the strength to overcome it.

But merely thinking of his boys’ suffering, and the unrelenting stress he and Ana faced, often would bring him to tears. He discovered it was better to just keep quiet about it.

“There were so many times we were in disbelief at what was going on,” Curt said. “For a long time, we wondered how far we could go without breaking.”

At first they didn’t know why their young twins, Austin and Christian, were so far behind their developmental benchmarks.

They were such wonderful, pure-hearted boys, so loving and innocent. Yet they often raged inconsolably, and grew increasingly violent and destructive.

Belatedly diagnosed on the lower-functioning end of autism spectrum disorder, the twins sometimes pounded their heads on the floor and kicked holes in walls, or bit themselves bloody – despite Curt and Ana’s every attempt to comfort them.

In 2008, Austin discovered where matches were hidden and set a fire in his bedroom that burned their house almost to the ground.

Now 22, the twins’ health and long-term care needs are still an issue, and their ability to communicate is limited, but their behavior is largely controlled.

Curt and Ana decided it now was time to reveal some of the details of their lives, hoping that their story might inspire others coping with extraordinary family challenges.

They have written a book, “Waiting for a Miracle,” outlining their experiences. It’s currently being shopped to publishers.

The book traces the dramatic twists taken in what appeared to be storybook lives: he the three-time Pro Bowl back for the Seattle Seahawks and two-time All-American at Penn State, and she the aspiring model from Brazil.

“We’ve got a better sense of peace about it now,” Ana said. “We still worry, but we can talk about it now, and for so long, even that was painful.”

“It’s been a jagged road we’ve traveled,” Curt added. “But here we are.”

The model couple

Fresh in from Brazil, Ana Teresa Mendes Costa might have been the only person in Seattle who didn’t know Curt Warner on sight. She was dressed in high-fashion Dior and modeling at the Bon Marche downtown when an athletic young man walked toward her in October 1989.

“He made me weak in the knees,” she recalled. “Truly, I’d never felt anything like that before.”

Had she known anything about football, she would have recognized Warner as a regional icon.

Warner was the third player taken in the legendary 1983 draft, behind only John Elway and Eric Dickerson. As a rookie, Warner rushed for 1,449 yards and helped the Seahawks grow from a quirky expansion team into a conference contender.

“Curt would have been one of the all-time great NFL running backs if he hadn’t gotten hurt,” said John Nordstrom, of the original Seahawks owners group. “He was the Russell Wilson of his day, great in every regard – in the community, in the locker room, on the field. He had it all.”

Curt and Ana were from different hemispheres geographically, and were raised in equally disparate social worlds.

Curt was the youngest in the only black family in the tiny coal-mining village of Wyoming, West Virginia, growing up in an unplumbed home on the banks of the heavily polluted Guyandotte River. Ana came from an affluent family in Belo Horizonte (Beautiful Horizon), Brazil.

He proposed on a snowy Valentine’s Day 1990, at dinner atop the Space Needle.

They were on top of the world, but their relationship was solidly grounded by their shared religious faith and the ingrained belief that family came first, above all else.

Upon retirement from the NFL, Curt bought a car dealership in Bellevue and they set about building the large family they wanted.

The family grieves then grows

Curt Warner watched the doctor’s face as he positioned the stethoscope at various places around the mound of Ana’s stomach. The baby was due any day, and was so large they were considering a C-section. Curt saw the doctor’s face darken as he searched for a heartbeat.

“The doctor told me the baby was dead inside me, and would be still-born,” Ana said. She was induced immediately. “I didn’t believe him. When Ryan was delivered, I kept waiting for him to cry. I kept waiting for a miracle.”

Ryan Warner never cried. His umbilical cord had encircled his neck and become pinched in the final days. Curt and Ana spent that night together in the maternity ward, the cries of healthy newborns echoing down the hall.

Thoughtful nurses gave Ana a stuffed bear to hold when she was wheeled from the hospital the next day so she wouldn’t have to cope with the anguish of being empty-handed. Ryan Warner was buried in a Bellevue cemetery, along with that little stuffed bear.

“You can’t prepare for a baby dying, for having a still-born,” Curt said. “Here’s the reality, you go home and you’ve got a room for the baby. But it’s empty. I couldn’t go in there for a long time.”

After Ryan’s death, Ana suffered a miscarriage. And then another. And another. Immeasurable grief compounded with each. “It felt like I had a hole in my heart,” Ana said. “The pain of losing Ryan was still there, hovering over me, still holding a piece of my heart.”

Son Jonathan was born healthy in 1993, and before he turned 1, Ana was told she was pregnant with twins. She looked toward the sky: “Lord, you have a real sense of humor.”

The twins were born without complication, but in time, they began climbing on everything, and were chewing on tables and chairs and window sills. They constructed a confusing vocabulary of incomprehensible sounds, and were well below the charts in every metric.

“We were having so many other issues, too, like hyperactivity,” Curt said. “By the time they were 2 or 3, they were out of control.”

Years of feeling helpless

When a doctor finally diagnosed autism, Ana Warner’s mind flashed to Dustin Hoffman in the movie “Rain Man.” It was the only context she had. And she immediately felt the weight of a mother’s assumed guilt.

“What did I do wrong?” she asked the doctor.

“It’s not your fault,” the doctor said.

“How could it not be?” Ana responded. “I’m their mother.”

In 1999, some doctors still recommended that children on the autism spectrum be placed in institutions, somewhere quiet, tucked away like a family secret. Stunned and confused, Curt and Ana could barely talk on the drive back to their new home, now in the Portland suburb of Camas, Washington. When they arrived, Ana raced to the computer.

Autism spectrum disorder has so many facets and a broad range of symptoms, but Ana knew with the first online search that the doctor was right.

“In a way, it was a relief,” she said. “At least we finally had a name for it.”

A team of therapists was gathered, and they shuttled to the Warner home for intensive treatments that filled 40 hours every week. “We tried everything they could think of,” Curt said.

Autism, the fastest-growing neurological disorder in America, is frequently diagnosed by the age of 2. But the Warner twins were almost 5 before diagnosis and the start of treatment. Curt and Ana feel the delay was an obstacle to mitigating the boys’ symptoms in the long run.

Christian, particularly, began one of the most alarming behaviors the Warners would deal with over the years: Head-banging.

Curt took pride in being able to take control of tough situations. But this was an existential test. “It’s your child, someone you love more than anything, and nothing you try helps them,” Curt said. “When they suffer, you suffer right along with them. It was years of feeling helpless.”

‘It was like a war zone’

Because they couldn’t keep their eyes on the twins every minute, the Warners turned their house into a fortress monitored by alarms and sensors. If they got out on their own, the twins couldn’t find their way home or tell anyone who they were or where they lived. The dangers could be life-threatening.

But the house was an environment they could control, where the twins could be kept most comfortable and safe. The stresses of unknown and crowded places sometimes set the boys off. And especially when the twins were young, public awareness of autism was limited. Bystanders were often cruel.

On a trip to try a new therapy for the twins, Christian threw himself down on the concourse of the crowded Denver airport and started screaming and banging his head on the floor.

“When the kids have a meltdown, there’s very little you can do; you can’t move them or try to take them anywhere,” Curt explained. “All you can do is be there for them, try to comfort them any way you can, and ride out the storm.”

Ana teared up as she remembered how Curt responded when the curious crowd gathered around Christian. “Curt got down on the floor, laid right beside Christian, talked to him quietly, trying to reassure him that things would be all right.”

The boys’ growth and early teen hormones added new and puzzling behaviors, and their inability to communicate compounded their frustration. “Puberty was a nightmare,” Ana said. “The boys destroyed the house. It was their way to express their frustration and anger, hitting and kicking walls and doors, breaking what they could.”

Neighbor Don Lovell was stunned the first time he went into the house. “You’d go over there and it was like a war zone,” Lovell said. “There were holes in the walls everywhere. Curt would work to fix two holes, and in half an hour, there would be two more kicked in a different wall. He just couldn’t keep up.”

Tested by fire

Austin Warner watched where his dad hid the lighter he used to fire up the two candles on the birthday cake for the Warners’ 2-year-old daughter Isabella. Curt and Ana knew that all sharp things and fire-starters had to be hidden.

A few days later, when the fire alarms broke the quiet of a February afternoon in 2008, Ana knew it was Austin. By the time she got upstairs, Austin’s room was ablaze. Eldest son Jonathan heroically led the other children safely from the home, but Ana suffered smoke inhalation in her futile attempt to put out the flames.

By the time Curt had raced home from the car dealership, everyone was out of the house and the fire department had vented the roof and soaked it down. But little remained except the outer walls.

“We always lived on the edge, but this was so unforeseen,” Curt said. “We didn’t have time to sit there and complain and go ‘woe-is-me.’ We got through the initial shock of it and regrouped. We had to think, what do we do next?”

Austin felt such guilt that he would punch himself in the face. Jonathan was angered by how his life had been altered, and was so different from that of his friends. And Curt set his jaw and leaned into the rebuilding of their lives.

But Ana put on a mask. Curt had no idea how dark her mood had become. “She could put up a pretty strong shield, like everything was OK, and she didn’t complain,” he said.

“Those were dark times, and it still hurts to think about how low I got,” Ana said. “For months, I didn’t want to live, I was too overwhelmed.”

She called upon Curt’s strength and her faith to work past what was later diagnosed as post-traumatic stress disorder. Because of that unwavering support, Ana calls Curt a “Hall of Fame husband.”

His greatest strength? Always being there. “I have no doubt so many lesser men would have given up and left. What we were going through wasn’t pretty, but he was just always present, always convincing me it was going to be OK.”

Everything was lost in the fire, including all of Curt’s trophies and sports memorabilia. But every family member escaped unharmed and Ana and Curt absorbed the lesson of it. “We learned it was just stuff,” she said. “Stuff isn’t what makes you happy. Your family is what makes you happy. And our family survived.”

In the aftermath, promising therapies and short-term progress for the twins often led to regression and frustration.

Dr. John Green III of Oregon City, Oregon, has treated the twins since they were early teens. The story of Austin and Christian “is the most difficult to tell because it’s so painful,” Green said.

“It’s so full of hope and despair; you know how many things (Curt and Ana) have put into it. I feel that there’s another message that can be conveyed: It’s about the deep love and commitment Curt and Ana have had for so long.”

A different kind of miracle

Curt Warner still believes that some day a medical breakthrough will allow Austin and Christian to enjoy what most would consider to be a more typical life. Ana is convinced that the dramatic growth in the incidence rate will lead to increased awareness and greater funding for autism research.

So, yes, they’re still waiting for a miracle. But after 20 years, they have a different perspective on what that means.

The twins graduated from special education high-school classes, and at 22 are now busy with adaptive employment at SEH of America in Vancouver, Washington. They still live at home. Ana still helps them shave.

Ana pointed to statistics showing that one of every 68 American children is on the autism spectrum, with the number much higher among boys (one in 42).

Both Curt and Ana have long studied the various theories on autism’s causes and have their own ideas, but, as Curt said, they have never wanted to be part of “a holy war about vaccinations.” The topic naturally is heated and emotional to those with autism in their lives.

“We’re not about blaming anybody, we’re just telling people what our experience has been and how we feel about it,” Curt said. “The way we look at it, if somebody can find a cure, we’re behind them 100 percent.”

Every family touched by autism has a unique experience, Ana stressed, and the children have such a remarkable range of abilities and potential.

As they look back, now, it’s easier for Curt and Ana to take joy in their boys’ wonderful personalities rather than focusing on the daily pains they all felt during the most frantic times.

Their twins are full-grown and strong, but they still take joy in getting their Christmas lists mailed to Santa. Austin can recite every detail of every Disney movie through history, but can’t tell you how many quarters make up a dollar.

Curt and Ana know the twins will need a structured and protected environment in the long term, so they’re examining live-in options for them. They worry how their own mortality would affect the twins’ future security.

Curt, 56, has been out of the car business and now runs Curt Warner Agency in Portland, an insurance firm handling a wide range of coverages for Farmers. Ana still tends to the twins and Isabella, now 11, and continues to research autism and promote autism awareness causes. She’s taking online classes to become a “health coach.” She has decades of hands-on experience.

“We’ve prayed for healing, and the boys aren’t healed, yet,” she said. “They’re still very autistic. But, as a family, we’ve had a great deal of healing. There was a healing in our hearts that we needed desperately.”

Just being able to look back in time and open up about the experience seems like progress to Curt.

“People ask, ‘How do you do it?’ ” Curt said. “Well, you just do it. You can’t just wait for a miracle, you have to get busy finding a way to live, one day after the other. And at some point you realize that maybe that was the miracle itself.”