Spokane clinicians circle up parental advice in new book

Perfect parents don’t exist. That impossible target misses what children need most for lifelong social and emotional security, say three longtime Spokane parenting experts.

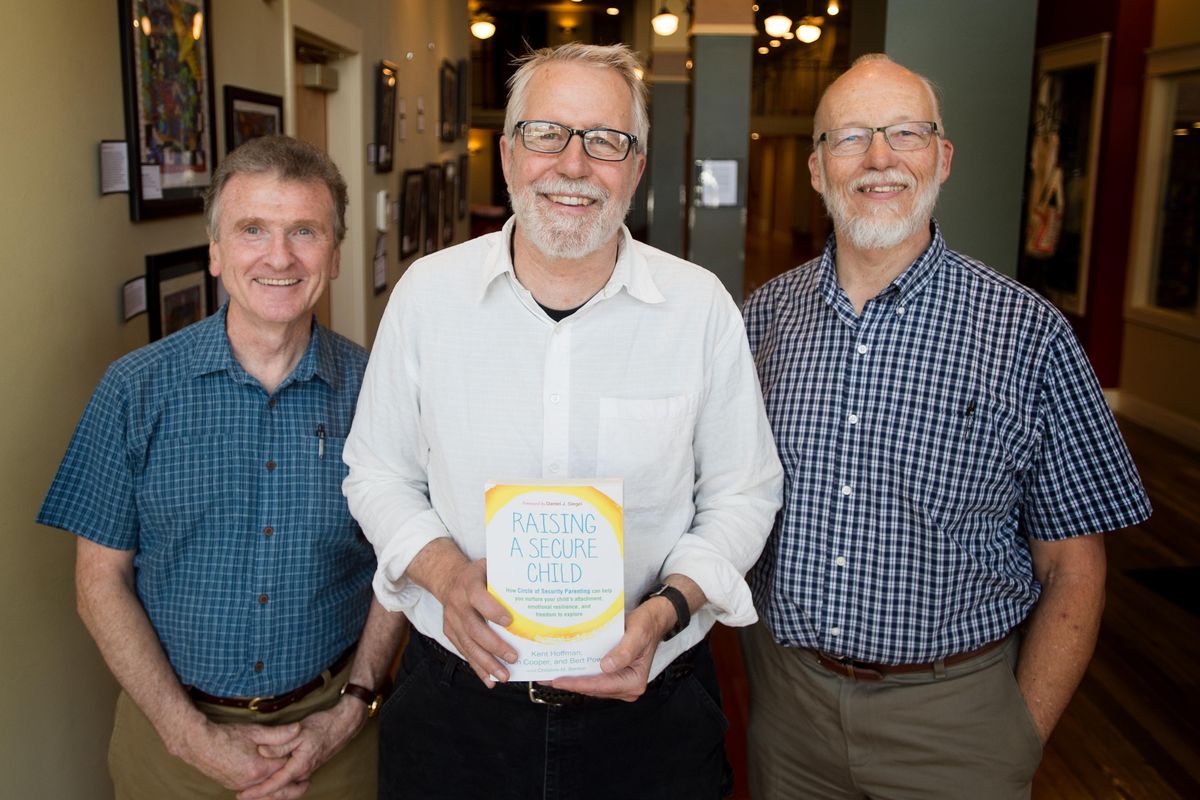

Circle of Security International founders Kent Hoffman, Glen Cooper and Bert Powell have developed early childhood intervention models that teach parents how to bond with their children in order to build a secure attachment. They regularly teach their protocols to professionals around the world.

Now in a newly released book, “Raising a Secure Child,” the group for the first time offers up parenting strategies in a self-help, nonacademic format geared to parents and caregivers. Their guidance is based on long-standing attachment research and the clinicians’ more than three decades of working with struggling families in Spokane.

“There is a relatively clear and simple way of understating what parents most need to know,” said Hoffman, 69. “We also wanted parents to know that trying to be perfect is actually a problem for children.

“The more we can trust ourselves, and trust the relationship, and not get anxious about doing it perfectly, we actually do better.”

Three basic parenting themes grounded in attachment research are fairly straightforward, according to Hoffman, who will read from the group’s new book Thursday at Auntie’s Bookstore.

The first big-picture theme is that parents need to be bigger, stronger, wiser and kind in their relationship with children, Hoffman said.

“Which is to say, children need to know someone is in charge in a really caring and kind way,” he said. “The danger is a parent will be in charge and won’t be kind, which ends up being mean, or they will try to be kind and they won’t be in charge, and that ends up being weak.”

“When families go to mean or weak, you’ve got problems. When they try to balance bigger, stronger, wiser and kind, you’ve got a pretty healthy family.”

The next two themes go hand-in-hand: All children need a fair amount of soothing and comfort, in a way that’s balanced with the third principle, that kids need autonomy or exploration, Hoffman added.

“Children need somebody to honor their need for autonomy,” he said, and that starts at infancy around 8 months. “Kids say basically, ‘I need to do this myself.’ ”

With those three essentials in place, a parent or other caregiver’s bonding with children creates that “circle of security” supporting their need for a secure attachment.

“We need a parent who is bigger, stronger, wiser and kind, who wants to support our autonomy when we want to explore, but also gives us soothing and comfort when we need that,” Hoffman said. “When all three are in place – this is what research makes clear – that ends up being a secure attachment. That’s the circle of security.”

Powell, 69, echoed that the group’s models center around attachment.

“It’s called safe haven,” Powell said. “If parents help children organize their feelings and soothe them when they’re distressed, children learn from that process of how to manage their own emotions. Then when children calm down, they naturally want to go out and explore, so it’s a model.

“If you want a child who is robust at exploration and robust at being able to manage feelings, they learn it in relationship. There’s no other way for a child to learn these things. Once learned, it carries you through life.”

The protocols grew out of the work Hoffman, Cooper and Powell did with families in difficult situations but with limited resources. The idea was to find efficient strategies for them, Hoffman said, while they studied the work of leading global researchers in attachment research.

Dave Erb, a now-retired Spokane psychologist, became an early influence on Circle of Security’s founders. Erb spoke about the concept of parents being like a dock, and teenagers leaving in a boat to explore and return to that safe dock.

“You can visualize that circle,” Hoffman said. The Circle of Security team developed an oval-shaped illustration shown in their work that depicts larger adult hands as a secure base and safe haven while children go out to explore and come back seeking support.

“Based on what we were learning, and then what we were doing, we came up with this protocol that’s kind of traveling the planet now called Circle of Security.”

“What insecurity is in the research is some parents refuse to encourage autonomy and try to keep kids close all the time, and some parents try to force autonomy, which is more like self-sufficiency, and say don’t even come in. All autonomy or all comfort ends up creating problems for kids.”

Cooper, 66, said Circle of Security typically helps families with young children experiencing problems in the home for various reasons, from poverty to the adults’ difficult histories.

“It’s helping them give their children a better start than maybe they had,” Cooper said. “The focus is really on the parents, versus trying to treat the child.”

The three psychotherapists started sharing their protocols as demand grew for their training from social workers, family therapists, mental health counselors and others. A publisher, The Guilford Press, also heard about their work and asked the group first to write a book for professionals published in 2013, followed by the latest parenting book released in February.

To write to a more general audience, the three worked with Christine Benton, a Guilford writer, to help make their clinicians’ language more readable, Hoffman said. However, he added that the three founders collaborated to write and oversee content, so it represents their combined longtime work.

Powell said as the group worked in person and through emails to write the book, they all kept a focus on translating what’s often presented in drier academic language into information more easily applied by anyone, while using real-life examples.

“There is an enormous amount of information, data and research,” Powell said. “There’s a huge gap between what is known and what is common practice in the world, really.”

“As you’re learning about a child’s attachment, the book tries to help adults see the world through a child’s eyes, and then also to see yourself.”

Cooper recently moved to Bellingham and is semi-retired but remains involved with Circle of Security’s work. Their collaboration is so intertwined over decades that they aren’t sure who came up with which idea, he said, but the book finds their common voice.

He emphasized the perspective that parenting isn’t about a focus on correcting behavior.

“I hope parents can shift from focusing on children’s behavior to looking at the behavior as their way of communicating that they have a need, particularly with misbehaviors or dysfunctional behaviors,” Cooper said. “If parents can make that shift, which is really a shift to empathy, that will make a profound change in the life of their kiddos.

“When we see behavior as something that we have to manage, control, or shape, we miss the underlying message about the need that the child has. Behavior is communication.”

Cooper also said the group wanted to help readers understand more about attachment and a child’s underlying need for both autonomy and connection.

“Our work has gotten such an enthusiastic reception around the world by clinicians, early childhood educators and home visitors, that we’re wanting to make it available to others who can make use of it more immediately, such as parents, foster parents, adoptive parents.”

Also this month, Hoffman will present a four-day training seminar in Spokane for professionals such as social workers and family therapists that starts June 26. The Circle of Security Parenting facilitator training at Gonzaga Law School will teach people how to work with groups of parents and caregivers using its materials.

For the general parenting book, Hoffman hopes readers walk away realizing they aren’t alone. When thinking about a circle of security, parents can reflect on where they struggle most, whether falling short at comforting, appearing mean, overprotecting, or giving in too much and appearing weak.

“All parents struggle somewhere; welcome to the club,” Hoffman said. “For parents to figure out where they struggle without blaming themselves, that’s where the action is.”