A year in the fields: Skagit Valley the heart of U.S. tulips, drawing hordes each spring

Muriel Kenyon stood in a field of color that sparked memories of her mother and grandmother.

“It looks like this beautiful quilt that you could just curl up in,” Kenyon said of the thousands of Skagit Valley tulips flashing brightly against the soft backdrop of a cloudy sky in April.

“It’s pretty magical,” she said.

Sixty miles south, Trinh Tran bought some of that magic with plans to fly it to Texas.

“I love tulips,” she said. “In Houston the weather is too hot.”

After a brief negotiation Tran struck a deal for dozens of tulips from a Pike’s Place seller. She’ll carry them on her late-afternoon flight back to Houston, injecting a jolt of Northwest color into her hot-weather home.

“I have never seen tulips this bright,” Tran said, marveling at the bouquet in her hands. “Every single time I come here I get at least two dozen to take home.”

Origins of a flower

Tran’s desire to bring those flowers home is not unusual. For hundreds of years tulips have been packaged and transported around the world – a testament to people’s love for the colorful blossom.

First domesticated in the Ottoman Empire, tulips quickly became a status symbol in the Ottoman royal court. The word tulip is derived from the word turban – a nod toward the visual similarity between the two.

Tulips were first imported into Holland during the 16th century, and Dutch traders and aristocrats quickly turned the flower into an industry. During the following century a tulip craze swept Holland, creating what some economists call the first speculative bubble. Bulbs of certain varieties could cost more than a home.

Hundreds of years later the tulip is still a sought-after commodity, filling mother’s day bouquets, grocery stores and yards.

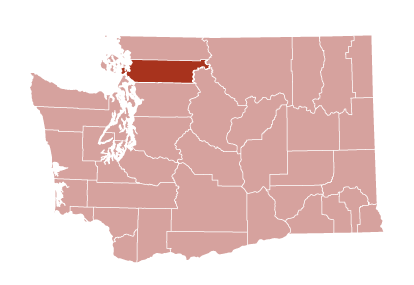

And while Holland remains the hub of the international tulip business, the Skagit Valley – a rich agricultural region of roughly a million acres between Seattle and Bellingham – is the heart of the tulip industry in the United States.

The valley’s roughly 450 acres of tulips represent 75 percent of U.S. commercial production. About 300,000 people visit the fields during the monthlong annual tulip festival in April. Those tourists help spin $65 million into the county’s economy.

“We see double digit increases in our sales tax from what is collected in March to what is collected in April,” said Cindy Verge, the executive director of the Skagit Valley Tulip Festival.

For one month every year tourists from all over the United States and the world descend upon the rural county. The attraction of those flowers may be obvious – bright beautiful colors – but Verge said there is a deeper, more primal motivation at play.

“I think it’s also a psychological thing,” Verge said. “You get done with winter and it’s like, ‘Please. Let’s have something bright and cheery.’ ”

The industry behind the bouquets

In 15 cavernous acres of greenhouse space, Washington Bulb Co. has made a business of packing and delivering “bright and cheery” tulips around the U.S.

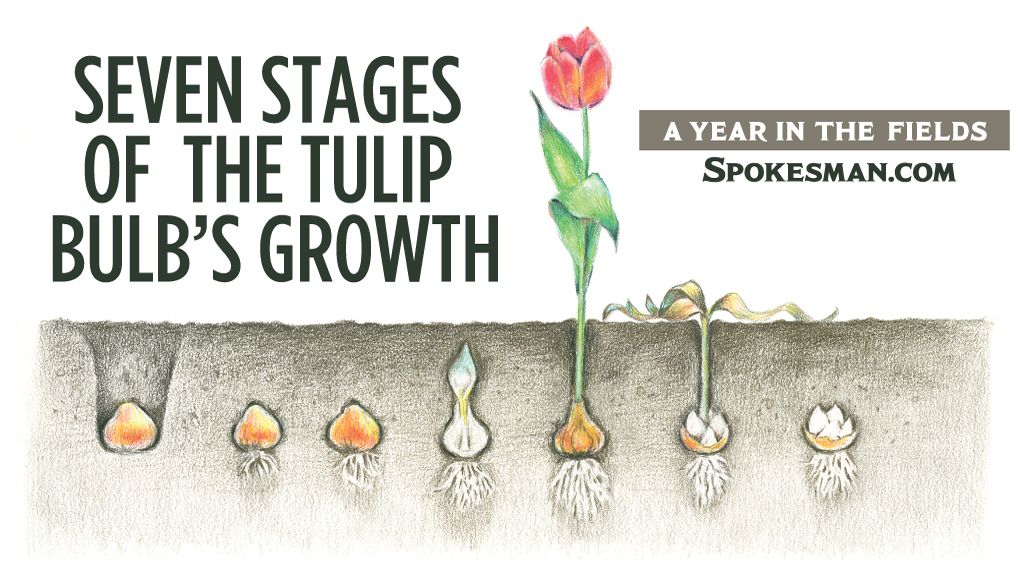

In late April tulips are prepared for the show of their lives.

“Mother’s Day is just insane,“ said Brent Roozen, standing in the large greenhouse his family built.

In the lead-up to Mother’s Day, workers make sure the tulips bloom at the same time and are collected into bouquets and packaged for shipping.

It’s a complex undertaking. “If you have millions of flowers going out on Mother’s Day you don’t want to be late,” Roozen said.

Roozen works for Washington Bulb Co., the largest tulip company in the United States. Roozen’s grandfather, William Roozen, immigrated from Holland in 1947 and started growing tulips on five acres of land in the Skagit Valley.

Now Washington Bulb Co. owns roughly 2,000 acres of farmland in addition to its 15 acres of greenhouses. Of those 2,000 acres, about 350 are dedicated to tulips, with another 450 dedicated to daffodils at any given time.

The company has done well and still is owned by the Roozen family, being run by William’s five sons. The company makes most of its money selling fresh-cut flowers. They grow tulips year-round in the greenhouses and ship fresh bouquets around the U.S.

Roozen said flowers cut one day can arrive in New York City at 9:30 a.m. the following morning.

After growing for a period in rectangular boxes, the greenhouse tulips are cut from their bulbs and shunted along a system of conveyor belts. Eventually they’re gently scooped up by mechanized claws and organized and arranged into bouquets, which are wrapped, boxed and loaded onto UPS trucks. Some head south on Interstate 5 to SeaTac, while others head east across the state to Spokane. Washington Bulb Co. supplies Spokane-area Rosauers with fresh tulips.

“What you order is what you get,” said Brent Roozen.

This side of the industry is not what most tourists see when they visit the tulip festival. Instead, they’re treated to the acres and acres of outdoor tulip fields, which bloom in April.

Since 1968, fresh cut prices have tripled while bulb prices have only doubled, according to Washington State University research. Since 2000 prices for both have decreased.

Fewer farms, fewer farmers

“Like any industry, there has been a lot of consolidation,” said Don McMoran, the director of the Washington State University Skagit Valley extension. “The bigger farms tend to get bigger.”

The trend toward consolidation in American farming is on full display in the Skagit Valley. In McMoran’s lifetime the number of bulb-producing farms has dropped from five to three. Of those three only two produce tulips, and Washington Bulb Co. dominates that industry.

The other tulip operation, Tulip Town, has about 10-acres of farmland dedicated to tulips and focuses mostly on tourism.

McMoran said there are numerous reasons for this consolidation. Increased global competition has forced operations to scale up in order to be competitive. For most consumers, place of origin doesn’t matter that much when it comes to tulips. And larger industries based in Holland or South America take some of that market share.

“A lot of the product is coming (from) outside of the country to fill our needs,” he said.

As in any agricultural pursuit there are bad years, pests, infections and other unforeseen and unavoidable problems.

“The bigger you are, the more you’re able to weather the bad storms,” McMoran said.

Cindy Verge, the executive director of the tulip festival, said the loss of tulip growers in the valley worries her.

“It’s very real that there are both economic and agricultural pressures,” she said.

Skagit Valley Bulb Farm, Inc's Tulip Town's tulips are seen on Tuesday, April 25, 2017, near Mt. Vernon, Wash. (Tyler Tjomsland / The Spokesman-Review)Buy a print of this photo

And despite the beauty of the tulips, at the end of the day tulip growers are farmers – and farmers need to produce.

“Farming is a business,” she said. “It’s a tight business and the margins aren’t real great.”

Unlike most crops, however, tulip farmers get what Verge called “two harvests” – the April flower bloom and the bulbs. And the bloom, which attracts hundreds of thousands of tourists, brings its own rewards.

“There are very few places in the world where you can see something like this,” said Brent Roozen. “Especially so near to a metropolitan area like Seattle or Vancouver.”

The peace flower

Jeannette DeGoede and her husband, Anthony, own Tulip Town. Relative to Washington Bulb Co., Tulip Town is a small operation, with just 10 acres of fields and no greenhouses. But DeGoede still thinks she has the best job in the world.

“I think it’s one of the most wonderful professions because you see people happy,” she said.

Instead of focusing on growing large acreage, the DeGoedes have doubled down on tourism.

A wraparound mural of Tom DeGoede’s ancestral Dutch home greets visitors when they enter Tulip Town. A garden, replete with windmill and pond, sits next to the farm fields. The DeGoedes bought their farm 37 years ago, and they just paid it off this year, Jeannette DeGoede said. For the last 25 years they’ve been showing flowers as part of the tulip festival.

A centerpiece of Tulip Town’s display is the International Peace Garden, one of many installed around the world.

The concept for Peace Gardens originated after World War II.

During the war the Dutch royal family fled to Canada after Germany invaded Holland. When the war ended, they gifted 100,000 tulips to the Canadian parliament. Now, the Canadian Tulip Festival in Ottawa is a yearly event and there are International Peace Gardens around the globe – including in the Skagit Valley.

Tulip Town’s garden was dedicated in 2007.

“We really want them to be a symbol (of peace) on our farm,” DeGoede said of tulips. “Because it’s just what this world needs. People don’t need any more wars.”

A visual reminder

It has been nine years since Muriel Kenyon’s grandmother, Virginia Kenyon, passed away. For the first time since her grandmother’s death, Kenyon visited the Skagit Valley tulip bloom this April.

“It always makes me feel close to her,” she said. “She was an incredibly smart woman.”

Kenyon, who owns and runs a winery in Walla Walla, didn’t come to the Skagit Valley with her mother this year. Instead, she texted her a picture of the flowers. Her mom responded asking, “Did you run through them and try and take a nap like you did when you were a little kid?”

Kenyon restrained herself, she said. But the impulse to “curl up” in the fields of tulips was still there.