Wildlife biologist, author has eye for creature ways

Wildlife biologists travel through the landscape with an educated eye for detail.

They’re like bird dogs, sensing more than most people would ever see. They make connections between critters and the land, trees and water.

A walk through the scablands, woods or wetlands of Eastern Washington with a wildlife biologist is a treat few of us get to enjoy. But anyone can increase their critter IQ by poring over their written words on those habitats and the creatures that inhabit them.

“There is life in deadwood,” observes wildlife biologist Lisa Langelier. “From the insistent hammering of the love-struck flicker advertising its availability or excavating his hole, to the elusive nocturnal northern flying squirrel, to the long-toed salamander who lays her eggs in rotten logs – deadwood is necessary for some animals to make a living.”

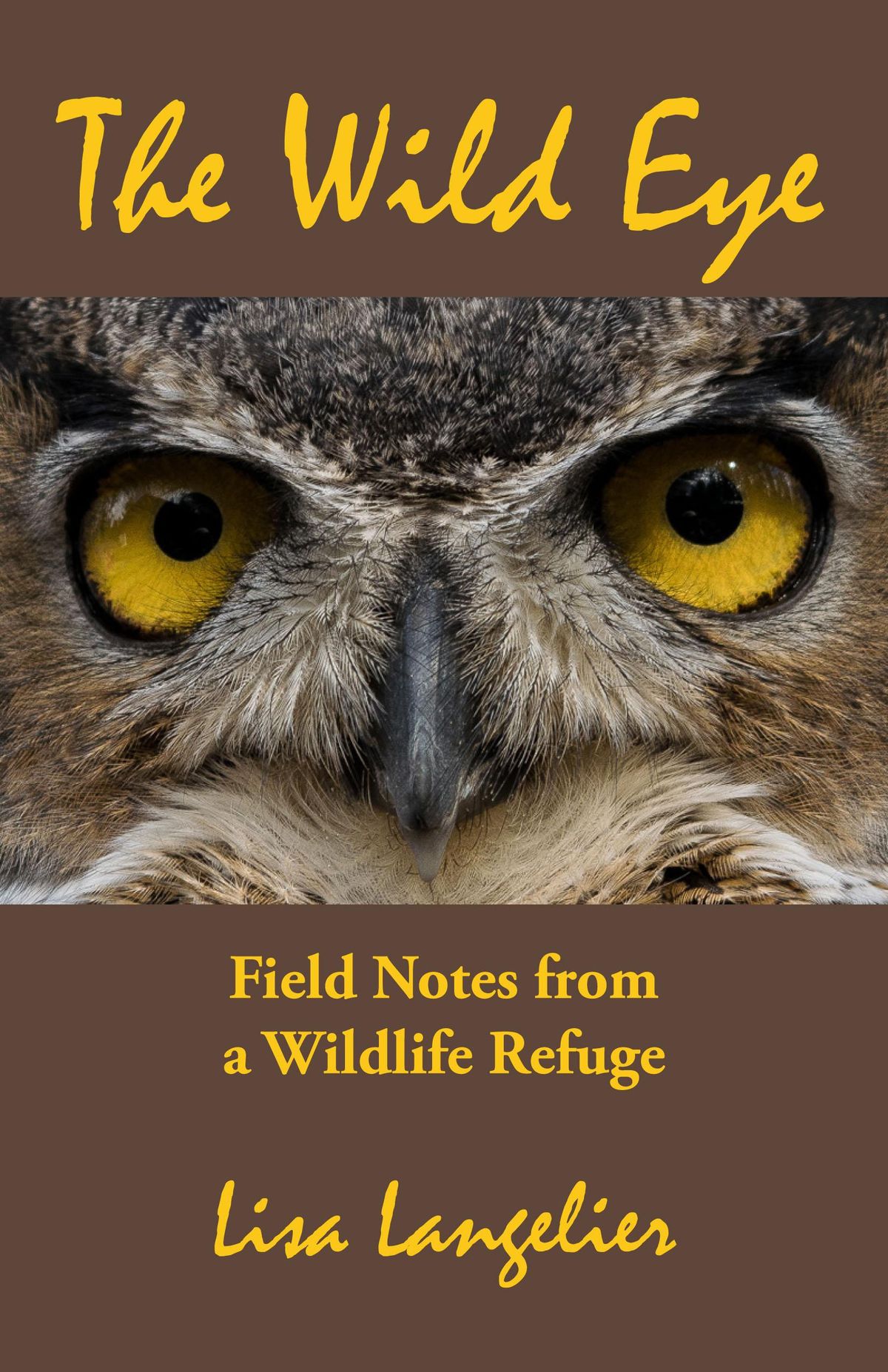

That’s the intro to one of 50 wildlife-related essays in her book, “The Wild Eye: Field Notes from a Wildlife Refuge.”

Before retiring, Langelier was a U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service manager at Little Pend Oreille and Turnbull national wildlife refuges. The book compiles years of observations she’s made about the field, from frogs to moose and aspens to “winged weeds.”

The pages are illustrated with laser-sharp images of area wildlife by Spokane nature photographer Tom Munson.

Langelier cuts through the professional jargon and uses clear language to detail creatures’ habits, ways and needs. She answers questions we’ve pondered and those we didn’t know enough to ask.

The beaver’s fur-lined lips seal behind its front incisors, allowing it to carry branches between its teeth while swimming, she explains among the countless details that describe how nature works.

While most of the book is devoted to native flora and fauna, she doesn’t overlook the impact of invasive species. She offers little appreciation for starlings. And “at McDowell Lake on the Little Pend Oreille National Wildlife Refuge,” she writes, “three alien species cause problems: tench, Eurasian Watermilfoil, and purple loosestrife.

“Nonnative aquatic invaders cost the United States $9 billion every year in associated damages and control costs.”

She finds a lot to like and admire about snakes. “Nothing that eats slugs can be all bad,” she notes. “Even when they are cold-blooded, hiss and crawl on their bellies flicking forked tongues.”

She admits to being a voyeur through the spring courtship and mating displays of birds. Hummingbirds, snipe and red-necked grebes catch her attention as they dive in the air or pair up and dance across the water in their versions of foreplay.

The essays are alive with numbers: “Imagine a 200-pound person gaining 20 pounds each day and losing it overnight!” she writes, describing the winter caloric challenge for a chickadee.

Her stats add perspective to something as overlooked as a dead tree: “Snags provide essential habitat for 85 species of North American birds that either excavate holes, use natural cavities or use holes created by other animals.

“Mammals, reptiles, amphibians and invertebrates use snags for nesting, perching, foraging, roosting, overwintering or hibernating. The existence of some fungus, moss and lichen depend on deadwood.

“That’s why it’s important to leave the best of these dead trees alone.”

Langelier is honest about her studied biases. “I have never met a beaver pond I did not like,” she writes noting that “equipped with chisel-shaped teeth, webbed hind feet and waterproof fur, beavers are second only to humans in their ability to manipulate the environment.”

In detailing the needs of wildlife, she hints at corresponding human needs.

Wetlands are essential for waterfowl, she says, as well as for groundwater purity.

The questions and amazement of her daughter when she was young piqued the biologist-author’s interest and imagination.

Even a scientist with a data-honed view of the world can benefit from the innocent perspective of a child. And we from them.

“The Wild Eye” will help anyone get more out of their precious moments with wildlife in the Inland Northwest.