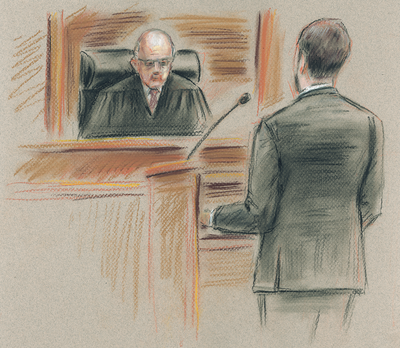

Federal judge questions civil torture suit against Spokane psychologists Mitchell and Jessen

The torture civil suit against two Spokane psychologists will continue to the next round, but a federal judge cast doubt Friday as to whether he’ll let the case proceed without direct evidence showing Bruce Jessen and James Mitchell interrogated two men who brought the suit.

U.S. District Court Judge Justin Quackenbush denied attempts by the attorneys of Mitchell and Jessen to gut the ACLU’s civil suit against them by throwing out the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence report under the argument that it was biased because it was commissioned by a Democrat.

But Quackenbush pointedly asked ACLU attorney Dror Ladin to identify the evidence that could show the psychologists personally helped in the interrogations of Sulieman Abdullah Salim and Mohamed Ahmed Ben Soud, who were suspected terrorists subjected to torture by the CIA in the early years of the war on terror.

“We are here at summary judgment,” Quackenbush told Ladin. “What factual evidence exists that would justify me to allow this case to continue?” in reference to allegations made by Salim and Ben Soud.

Salim, Ben Soud and the late Gul Rahman were tortured, according to court records, based on interrogation techniques designed and sometimes carried out by Mitchell and Jessen.

Quackenbush noted that references in thousands of pages of documents make clear that Jessen participated in the interrogation of Rahman, who was placed in a diaper and short-chained to the floor and died of hypothermia in his cell. But Quackenbush questioned the ACLU’s case that the two psychologists were to blame in the torture of Salim and Ben Soud.

Ladin kept trying to make his case, with many interruptions, that Mitchell and Jessen came up with methods for the CIA to use against detainees. Mitchell and Jessen then employed those methods against Abu Zubaydah, who erroneously was believed to be a top leader of al-Qaida.

Zubaydah underwent sleep deprivation, extreme confinement, forced nudity and physical assaults. All told, he survived waterboarding 83 times over 17 days, and Mitchell and Jessen oversaw much of the torture, according to court records.

Ladin said Mitchell and Jessen then used those same torture techniques on dozens of other detainees, including Salim and Ben Soud.

“I don’t want to say they laid hands on Salim or Ben Soud,” Ladin said of Mitchell and Jessen. “What we needed to show was a connection to that abuse. What matters is the defendants were the ones who provided the tools and theory for torture … and said it should be used on detainees.”

But Quackenbush openly questioned that legal connection.

“The only real reservation I have is the sufficiency of the evidence as it applies to Salim and Ben Soud,” Quackenbush said. “I’ll be giving you a written opinion.”

In another argument, Quackenbush denied the motion by attorneys for Mitchell and Jessen to bar the ACLU from using information gleaned from the 2014 Senate Select Report on Intelligence under the argument that it wasn’t trustworthy because the study was conducted under the direction of a Democrat.

“The court’s denial of defendants’ request to bar consideration of the Senate torture report was also, we believe, the right outcome,” Ladin said in a statement after the hearing.

The trial remains set for Sept. 5 in Spokane, but Quackenbush again implored the sides to try to settle the case before it goes before a jury. He noted that the federal government is paying for the team of defense attorneys for Mitchell and Jessen and would also fund any potential cash award by a jury.

“I will not allow it to become a political trial” about whether the George W. Bush administration wrongfully interrogated detainees following 9/11, he said.

“The trial is about whether these detainees were subjected to torture,” Quackenbush said, “and did the plaintiffs legally aid and abet that torture.”