Push to turn over federal lands to the states may be losing steam

A Utah congressman’s abrupt reversal on a proposal to sell 3.3 million acres of public land across the West is significant, and may be part of a shift in the Republican Party’s thinking on federal land ownership, conservation groups say.

U.S. Rep. Jason Chaffetz tweeted Wednesday evening that he was withdrawing the legislation, following outcries from hunters, anglers and other public lands advocates.

“…groups I support and care about fear it sends the wrong message,” Chaffetz wrote in the tweet, adding that he was a “proud gun-owner, hunter and love our public lands.”

“This is the first time I can recall that anyone floated something out there and then backed down,” said Jonathan Oppenheimer, the Idaho Conservation League’s government relations director. “Maybe the message is getting through to some of these politicians that it’s a deeply unpopular idea. There’s simply not a groundswell of support for these lands being sold or turned over to states.”

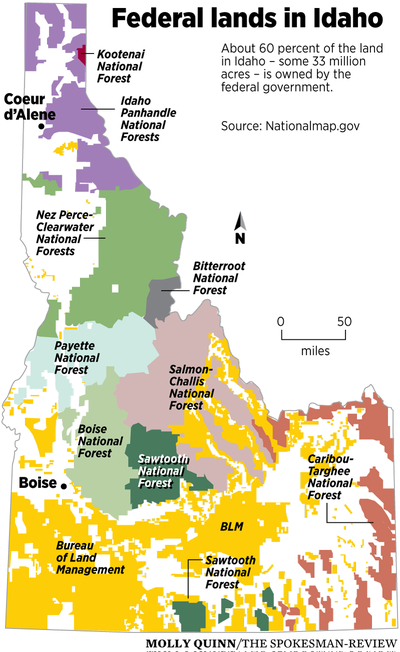

About 60 percent of Idaho is owned by the federal government. And for some rural residents, the idea of a state takeover of national forests and grazing lands has enduring appeal.

Local governments often say states would be better land managers, more attuned to nearby residents’ concerns and more receptive to logging, grazing and other activities that could help increase the tax base in struggling rural communities.

In 2013, the Idaho Legislature passed a resolution demanding that the federal government “immediately transfer title to all public lands” within Idaho to the state government. An interim committee was formed to identify a process for management and transfer of the lands.

When state Attorney General Lawrence Wasden pointed out legal problems with the approach, committee members hired the chief legal counsel from the Bush administration’s Interior Department for a second opinion.

But Idaho Gov. Butch Otter isn’t among the supporters. He often cites the 2015 fire season as an example of how difficult it would be for the state to pay for management of Idaho’s 33 million acres of federal land.

Wildfires that year burned 740,000 acres in Idaho – a land mass larger than Rhode Island. Firefighting costs topped $300 million. The federal government picked up 70 percent of cost, with the state shouldering the rest.

“When you have a bad fire season, the bill on the federal lands gets into the hundreds of millions of dollars,” said Jon Hanian, Otter’s press secretary. “If the feds weren’t there to pay for it…you’d blow a huge hole in the state budget.”

Even if logging increased on those lands, the extra revenue wouldn’t be sufficient to cover firefighting costs during a bad wildfire year, according to a study by the Conservation Economics Institute in Boise.

The study, paid for by the Idaho Conservation League, projected an annual deficit of up to $250 million if Idaho were to wrest lands away from the federal government. The study projected increased revenue from logging but subtracted costs for fire suppression, timber management, recreation and road maintenance.

Management, not ownership

Industry groups also have expressed reservations about a wholesale transfer of federal lands to states.

“We’ve never taken a stance. We’ve stayed on the sidelines,” said Laura Skaer, executive director of the American Exploration and Mining Association, which is based in Spokane.

The association has supported small transfers of federal lands to rural communities, which resulted from negotiated agreements among stakeholders. But Skaer said association members don’t have a consensus on widespread transfer of federal lands to the states.

Idaho Forest Group, which owns five sawmills and is the state’s largest lumber producer, hasn’t signed on either.

“Utah has spent millions of dollars trying to figure this out,” said Bob Boeh, the company’s vice president of government affairs. “We see it as a waste of energy that takes focus away from solving the real problem, which is active management of federal lands.”

Idaho Forest Group works with stakeholder groups to find consensus and harvest more timber from national forests. Company officials have also been supportive of the “Good Neighbor Authority,” a provision of the 2014 Farm Bill that allows states to enter into contracts to log federal lands, speeding up restoration work. The first North Idaho project is being planned in Bonner County.

“We think it’s all about management and not about ownership,” Boeh said.

Otter takes a similar stance, said Hanian, the governor’s press secretary.

“With the federal government under new management, we hope to see a lot more input from states,” he said.

Public access a priority

State takeover of federal lands still has advocates in the Idaho Legislature.

Rep. Judy Boyle, a rancher from Midvale and former natural resources adviser to the late U.S. Rep. Helen Chenoweth-Hague, R-Idaho, said she’ll continue to push legislation she introduced last year that spells out how the state would manage lands acquired from the federal government.

Boyle couldn’t be reached for comment, but she told the Capitol Press that she’s optimistic about federal land transfer receiving a serious vetting under the Trump Administration.

She has an ally in state Sen. Steve Vick, R-Dalton Gardens. “I think it would be best for Idaho if we owned those lands,” he said.

But Vick said he takes a nuanced approach to federal land transfers. He envisions a process that would unfold slowly, with Idaho gradually gaining control of federal lands. The state would have to demonstrate to the federal government – and its own citizens – that it could manage the lands to reduce fire danger, preserve public access and keep the land in state ownership, he said.

Access to public forest land is a big deal in his largely conservative district.

“It’s not my intent to sell off public lands,” Vick said. “Most of the people I talk to don’t want to see the lands sold either.”

Though a plank in the National Republican Party platform supports transferring federal land to the states, both President Donald Trump and his Interior Secretary nominee, Rep. Ryan Zinke of Montana, have opposed it.

An ‘enduring legacy’

Public lands advocates say they aren’t letting their guard down.

Last month, House Republicans changed the way Congress tallies the cost of transferring federal lands to state and local governments, a move that would make it easier to sell or transfer federal lands.

Brad Brooks, the Wilderness Society’s deputy director in Idaho, called the change troubling. It removed a scoring system that forces Congress to calculate the loss of future revenue from the sale or transfer of federal lands, and show whether the lost revenue could be offset.

“You can hold up a bill that will cost the taxpayers a lot of money on procedural grounds,” Brooks said. “This change makes it easier for people who want to sell public lands to get their bills through Congress.”

If federal lands transfer to the state, they’re vulnerable to being sold or swapped for other parcels, he said.

Last year, he requested the public records for 125 years worth of state land sales in Idaho. Brooks concluded that the state has sold off 1.7 million acres of land, or 41 percent of the acreage deeded from the federal government since statehood in 1890. State officials put the figure closer to 33 percent, saying Brooks’ calculations don’t reflect land swaps and new acquisitions. Most of the sales occurred before 1940, according to the state.

“If I wanted to privatize public lands, knowing that selling public land is an unpopular idea … I would get them in the hands of the state,” Brooks said.

Transfer of federal lands to the states is a recurring idea, one that seems to pick up steam in 20-year intervals, said Oppenheimer, of the Idaho Conservation League. But the latest round may be waning, he said.

In Wyoming, the president of the state Senate recently announced he was killing a bill related to transfer of federal lands to the state. It won’t get a hearing this year.

“These lands are an enduring American legacy,” Oppenheimer said. “The opposition runs the gamut from hunters and ranchers, to bird watchers and hikers, and to the 90-year-old grandma who might not have the leg strength to explore it, but simply knows it’s there.”