25 years after Ruby Ridge, our divisions have grown

FILE – Federal agents and members of the media tour the outside of Randy Weaver’s home Sept. 1, 1992 near Naples, Idaho. Confiscated guns and ammunition are displayed on the ground following the end of the 11-day standoff. (GARY STEWART / ASSOCIATED PRESS)

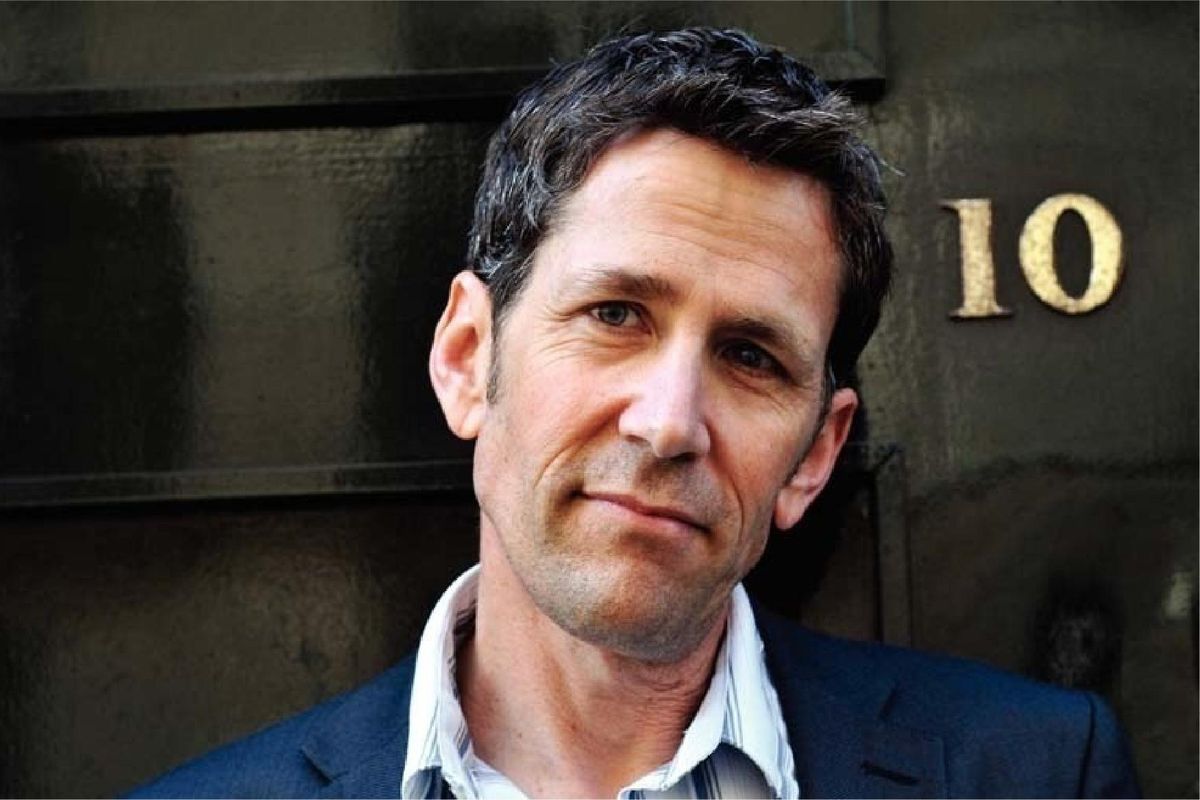

Twenty-five years ago this summer I sat in a trailer in North Idaho trying to convince a white separatist holding a gun that I was not an FBI agent.

I explained that I was a reporter from Spokane looking for insight into his old neighbor, Randy Weaver – the figure at the center of the shootout and 11-day standoff at Ruby Ridge.

His eyes narrowed. I didn’t “look like a reporter.” And how did I explain the “fed car” I was driving? (It was a company car, a Ford Tempo checked out from The Spokesman-Review garage.) And what about my “fed haircut?” (My dad cut my hair then and he had only two styles: crew cut and flattop.)

But nothing I said could convince him.

I find myself thinking about that frustrating, surreal conversation, and about Ruby Ridge, more and more lately, as I watch our country riven by these deep divisions – not just political differences – but a chasm of seemingly alternate facts, of entirely different realities. Communication without trust is difficult, but without agreement over basic reality, it’s impossible.

In 1995, three years after the standoff, I published a book about Ruby Ridge. I mined tens of thousands of pages of transcripts, wiretaps, reports and letters. My researchers and I interviewed a couple hundred people from every part of the case, from Weaver’s family in Iowa to the jurors in the trial, from Sara Weaver to the FBI agents and U.S. marshals. I endeavored to tell as complete and as objective a version of the story as possible.

And ever since, I’ve watched people cherry-pick only the details from the case that fit their own idea about what Ruby Ridge means, either:

A. How the insidious sicknesses of white supremacy, paranoia and guns led to the death of a decorated federal agent, a mother and a 14-year-old boy, cost millions of dollars and destroyed careers. Or …

B. How government overreach and deadly law enforcement arrogance and mistakes led to the trampling of individuals’ rights, the destruction of a family and the erosion of faith in our institutions.

Of course, the correct answer, in Ruby Ridge at least, is C., all of the above.

F. Scott Fitzgerald once defined a “first-rate intelligence” as “the ability to hold two opposed ideas in mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function.”

But something about Ruby Ridge turns many otherwise intelligent people into second-rate thinkers. I suppose it’s the mix of so many complex and divisive themes, so many discordant ideas hard-wired into America’s history – race, religion, guns, law enforcement and Western mythology.

That inability to see both sides clouded the case from the very beginning, and my attempts to tell the story. For more than a year, every New York publisher rejected my book proposal, usually objecting that the story had “no good guys” and that I needed to “pick a side.”

Twenty-five years later, we have certainly picked our sides. We are a country sick with second-rate thinking, so rutted in partisan politics that it takes just five minutes flipping “news” channels to feel rather hopeless. Our own opinions echo back at us in social media feeds, memes and tweets, in short-attention-span bursts that reinforce and entrench our worldviews. We root for the news now like fans of opposing sports teams. We hold our breath and wait for the mass killer’s political views to come out so we can say, “See!”

And because we can’t even agree on a basic set of facts, we waste time arguing false equivalencies, like whether science and the rejection of science deserve equal hearing, or whether neo-Nazis and people angrily protesting them are equally to blame for a deadly riot (as if blame will settle something).

Sometimes it seems like the whole country has become the two sides at that roadblock at Ruby Ridge, seduced by paranoia, by the reduction of complex ideas into protest signs and bumper stickers or, now, into 140 characters, into two intractable sides.

Sometimes I wish there were a bipartisan commission to agree to basic facts. They could start with gravity, or that the Earth revolves around the sun. Or perhaps some other self-evident truths, perhaps that all men are created equal or that they are endowed with unalienable rights like life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.

Those founding ideals were the themes of Ruby Ridge, too: Randy Weaver’s self-fulfilling apocalyptic belief in white supremacy leading to a tragic confrontation with federal law enforcement agents whose brutal missteps and cover-ups violated the Weavers’ life and liberty.

Still, the Ruby Ridge question I get more than any other is a binary one: Yeah, but who was really to blame, as if, in my attempts to give an objective telling of the story, I have somehow held back. And when I give the only reasonable answer – both sides were to blame – invariably whoever has asked the question leaves disappointed.

This is the world we live in now.

Every Thanksgiving dinner, high school reunion, Facebook post, conversation with a neighbor offers the possibility of encountering someone fully entrenched on the “other side.” Our conversations are like Beckett plays, two characters miscommunicating so profoundly it might be funny if it weren’t sad.

It reminds me of sitting in that Idaho trailer 25 years ago, a scared young reporter trying to get information from an avowed white separatist. (Or, in his view: a sneaky undercover FBI agent trying to trick a God-fearing patriot into saying something incriminating.)

Every explanation I offered that day only convinced him more of what he already believed. He laughed. He scoffed. Of course a federal agent posing as a reporter would have newspaper business cards and a fake ID and a cover story like mine. In fact, he said with great pride, my whole story had proved his point. When the “interview” was finished, I thanked him for his time and said I’d send him a copy of my story when it was finished.

“Don’t bother,” he said. “I already know what it’s going to say.”