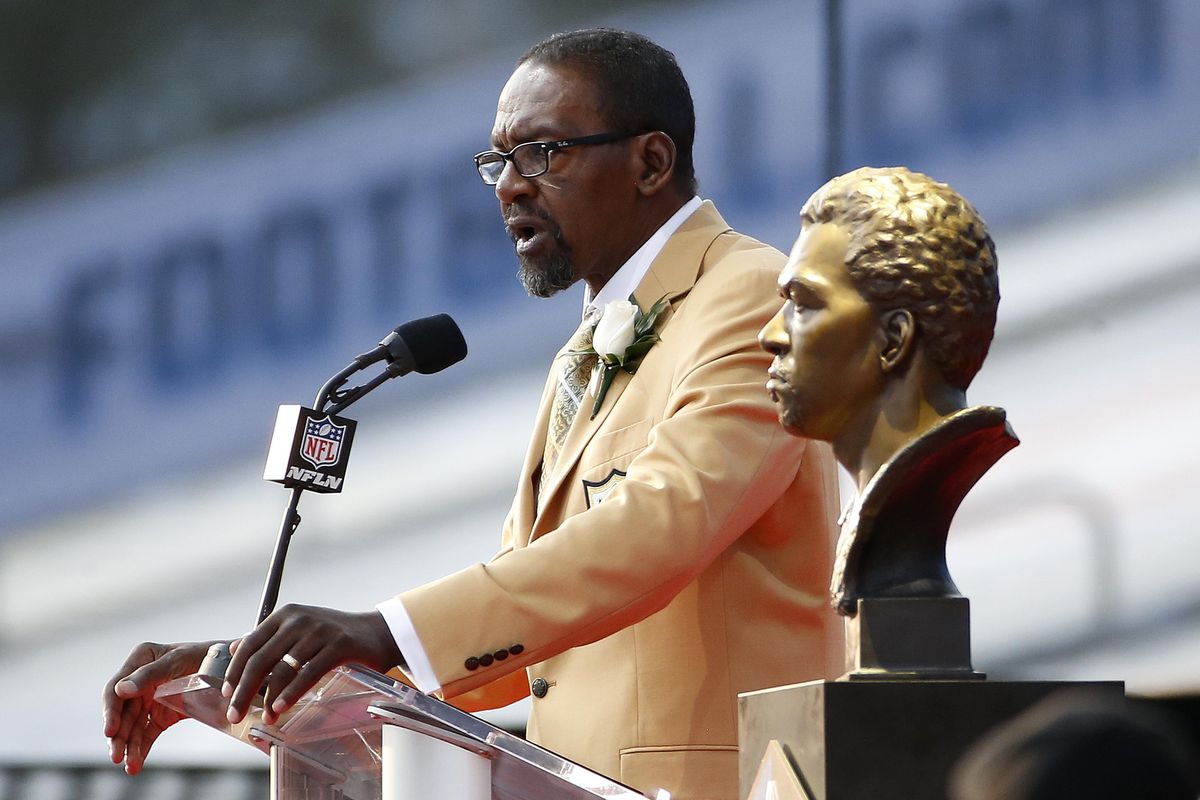

Hall of Famer Kenny Easley thankful for Seahawks owner Paul Allen, stands up for Black Lives Matter

CANTON, Ohio – Kenny Easley may have been as great as any player in Seahawks history but he often seemed as distant as any of the team’s legends.

Easley played seven incredible years as a safety for the Seahawks from 1981 to 1987 before a contentious ending to his career resulted in him largely disappearing from view for 15 years before current owner Paul Allen helped bring him back into the fold in 2002.

So maybe it made sense that a roughly 25-minute speech Saturday celebrating his official enshrinement into the Pro Football Hall of Fame – becoming the fourth player who spent his entire career in Seattle to be inducted – was largely devoted to issues outside of football and to Easley’s life before and after the NFL.

While Easley made no mention of any team executive from his time with the Seahawks from 1981 to 1987, he noted that it was Allen’s call in 2002 asking him to agree to become a member of Ring of Honor that led to him renewing relations with the team and the NFL.

“Thank you, sir, for reaching out to Kenny Easley in 2002 after a 15-year isolation from the organization,” Easley said of Allen in a speech that kicked off the official Class of 2017 enshrinement ceremony. “I believe in the old adage water runs downhill and thus winning starts at the top and you have run a great organization with a terrific head coach in Pete Carroll. The Seahawks back to the Super Bowl? How does that sound?”

Easley retired in 1988 when it was discovered he had kidney damage that he alleged was due to an overdose of painkillers prescribed by Seahawks trainers due to an ankle injury. A trade to Arizona was aborted when the condition was found. Easley later sued the team with the Seahawks eventually making an out-of-court settlement.

That Easley’s career ended suddenly at the age of 28 and after just seven seasons – during which he was named to five Pro Bowls and won Defensive Player of the Year honors when the Seahawks went a then franchise-best 12-4 in 1984 – resulted in him receiving little consideration for the Hall in 1992 when his name was first raised.

Easley thanked those who led a revival for his candidacy, including NFL writer Frank Cooney and longtime fan and current Minnesota school teacher Bob Kaupang, whose efforts helped result in his nomination by the Senior Committee last summer and eventual election in February.

“The Hall of Fame was dropped on the shoulders of Kenny Easley like a pair of shoulder pads,” he said. “Some folks said I deserved to be in the Hall earlier. I don’t believe that. Others said, ‘Maybe he didn’t play long enough.’ I don’t believe that either.”

Instead, he feels the Hall of Fame election came at just the right time.

Early in his speech, Easley mentioned three former Seahawks teammates – defensive end Jacob Green, offensive lineman Reggie McKenzie and quarterback Dave Krieg – saying he thinks each are among those who should get inducted into the Hall someday.

“Nineteen years in the NFL,” he said of Krieg. “Who would have thunk it?”

Of Green, he noted that it is “30 years removed (and he) is still the Seahawks’ all-time sacks leader.” Easley also cited Shaun Alexander as a player he thinks deserves induction someday.

Later, Easley mentioned longtime Seahawks fan “Mama Blue” – whose real name is Patti Hammond and was in attendance and shown on the big screens as he talked – and said the fans who filled the Kingdome in that era “made and still make pro football really fun in the Pacific Northwest.”

Then he made a request of “Mama Blue.”

“You were part of something in the ‘70s and ‘80s called ‘The Wave,’ ” Easley said. “Well I am going to ask you a favor.”

The favor, Easley said, is for Seahawks fans to do The Wave when he plans to be in attendance for the Oct. 1 game against the Indianapolis Colts to honor the players of the ‘70s and ‘80s.

“Can you do that for a brother?” Easley asked.

Easley was introduced by Tommy Rhodes, his coach at Oscar Smith High in Chesapeake, Va.

Along the way, Easley recalled his longtime rivalry with Ronnie Lott – a defensive back at USC when Easley was at UCLA – and said he would settle the debate over who was better by saying of Lott that “he was the best. There, it’s settled because I said so.”

He talked of the support of his wife of 35 years, Gail, his three children, his mother who he said had fallen ill in the past week and was unable to attend, and his deceased father, Kenny Sr.

He talked of the importance of his religious faith, citing Philippians 4 and 6 throughout his speech.

And he also took the moment to mention how sports can help society deal with its most important issues

“Please allow me this moment for a very serious message for which I feel very strongly about,” he said. “Black Lives do matter. And yes, all lives matter, too. But the carnage affecting young black men today, from random violence to police shootings, across the nation has to stop. We’ve got to stand up as a country, as black Americans, and fight the good fight, to protect our constitutional right to keep people from dying while driving or walking down the streets for being black in America. It has to stop and we can do it. And the lessons we learn in sports can help.”