Spokane historians to re-enact the city’s great 1889 fire, on Twitter

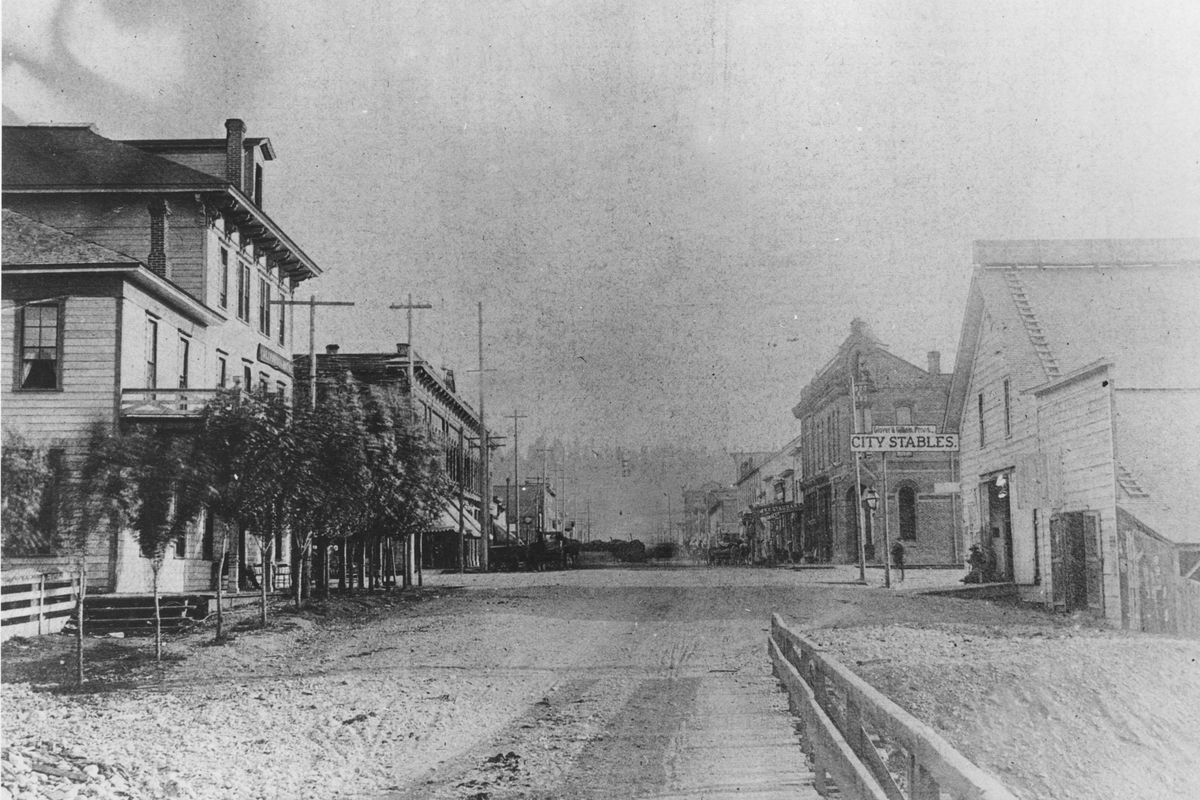

Then, as now, smoke hung in the pines overlooking the young pioneer town beside the Spokane Falls. Area forests were ablaze. People and horses trudged along the dusty streets in the heat of an August afternoon. Little did they imagine that the buildings they passed within hours would catch fire and collapse into 32 blocks of ruin.

Friday, 128 years later, Spokane history lovers plan to re-enact the day their city burned to the ground.

Their theater will be Twitter, and rather than “fake news,” the enactment will be an authentic re-telling, assembled by local historians from the archives at the Northwest Museum of Arts and Culture.

Thursday afternoon in the MAC’s archives room, a half-dozen history experts mined for nuggets of history, poring over yellowed photographs, letters, academic reports and newspaper microfilm. Some of the materials have rarely seen the light of day.

Several months ago the museum acquired a letter written days after the fire by one Charles Oudin, who was visiting Spokane during a tour of the West. In flowing penmanship, Oudin describes his escape from the Pacific Hotel before it collapsed in flames. His letter recounts the firefighters’ battle: “everybody cried for water,” he wrote, but there was none. Along with his letter, the museum received photographs he took the next day. Faded to a golden brown, one tiny print shows a white tent, pitched along the street. Oudin’s handwritten caption: “First shop opens after the fire – Spokane Falls.”

After news of the disaster swept the nation, the city of Portland sent a shipment of hams to help feed Spokane. But members of the Spokane City Council crept into the distribution warehouse and stole some of the meat. “They became known as the ‘Ham Council,’” said Larry Cebula, one of the researchers for the Twitter event. Cebula is a professor of history at Eastern Washington University.

As newspaper archives show, the flames that destroyed the city on Aug. 4, 1889, also lit a fire under the pioneers’ ambition. Within days, a tent city sprang up to carry on the work of lending money, selling groceries, publishing newspapers and slaking the hot summer thirst for a cold beer. Within weeks, the ashes had been hauled away and scaffolding began to rise along the downtown streets as workers erected a new city, this time built with bricks.

One of the many builders was a young entrepreneur named Louis Davenport, who opened a new waffle restaurant from which a world-renowned hotel would someday grow.

Another, known as Dutch Jake, opened a beer garden and gambling emporium in a 150-by-50-foot tent capable, according to some accounts, of holding 1,000 people.

The Spokane Daily Chronicle cranked out newspapers from a tent, not missing an edition.

City leaders laid plans for a more effective fire department.

A brand-new company known as Washington Water Power began work on a downtown hydroelectric plant, stringing wires through the recovering city and launching an electric-powered streetcar system.

In the 900 block of West Riverside the newly built Crescent dry goods store had scheduled a grand opening for Aug. 5, 1889 – and escaped the flames. When its doors opened the morning after the fire, the store sold everything on the shelves – and remained a popular Spokane institution for a century.

The fire that triggered the transformation was itself quite a drama.

According to newspaper archives, it began in a rooming house near the current location of the Davenport Hotel’s parking garage. Flames shot from a window. Volunteers ran to the scene with hand-drawn firefighting carts. At first, bystanders declared that a few buckets of water should do the job.

But the onlookers soon noticed firefighters racing around in panic, their hoses spouting an inadequate dribble. Water mains held no pressure. The superintendent of the city water works was on vacation, and his frantic replacement could not restore the flow. The water mains, investigators found later, had sprung a large and untimely leak.

Flames spread from building to building. Kegs of gunpowder exploded, flinging one roof high into the air. Soon, firefighters blew up buildings deliberately, hoping to stop the conflagration’s spread.

The Spokane Falls Review described the disaster in its Aug. 6, 1889, edition:

“The terrifying shrieks of a dozen locomotives commingled with the roar of the flames, the bursting of cartridges, the booming of (gun) powder, the hoarse shouts of men, and the piteous shrieks of women and children. Looking upward a broad and mighty river of flame seemed lined against the jet-black sky. Occasionally the two opposing currents of wind would meet, creating a roaring whirlwind of fire that seemed to penetrate the clouds as a ponderous screw, while lesser whirlwinds danced around its base, performing all sorts of fantastic gyrations. … In this manner the appalling monster held high carnival until about 10 o’clock, when with a mighty crash the Howard Street bridge over the Spokane River went down.”

“All the banks, all the hotels, the post office, the land office, all the large business houses” were destroyed, the Review reported.

Thirty-two blocks lay in ruins. Only one man died – leaping in his nightshirt from the window of his burning hotel.

Over the city’s two remaining bridges, at Washington Street and Post Street, “a terrified and motley stream of homeless people passed, seeking shelter under the pine trees and relief from the smoke and din of the ruins,” the newspaper reported.

“They were not heavily burdened, for there were few downtown dwellers who had time to save anything of value. Some had blankets, others pillows and few carried bundles on their backs, but most of them were scantily attired and bankrupt of all personal effects. Among these latter were many theatrical and ‘sporting’ people (a euphemism for gamblers, drinkers and prostitutes), who were in great distress, for they lost not only all they possessed, but their means of earning a livelihood was gone.”

It was Tom McArthur, public affairs director at the Spokane Association of Realtors, who hatched the idea for Friday’s Twitter re-enactment. He said he called some of his historian pals last week and asked, “Wouldn’t it be neat to use a modern communications tool to tell this old story?” They jumped at the chance.

At the planning session Thursday afternoon, the historians chuckled over a thought that Friday’s tweets could make people think Spokane was on fire again. “We don’t want another ‘War of the Worlds,’” joked Cebula, recalling the 1938 radio broadcast about an invasion from Mars. And so it was that the committee drafted a warning: “This museum will be live tweeting the great fire of 1889. Do not be alarmed. Have a nice day. #GreatFire1889”