Chronic absenteeism in Spokane-area schools a persistent problem

Missy Scott, a counselor at McDonald Elementary School in Spokane Valley, remembers the time a student asked her to send a letter home imploring the parents not to “forget I have to be at school.”

“If kids aren’t here, how can they access their education?” Scott asked.

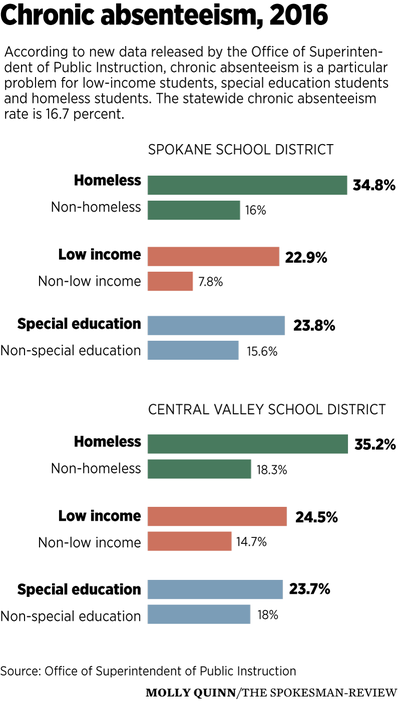

Students who are chronically absent from school are less likely to graduate. And according to data released by the Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction last week, chronic absenteeism is a particular problem for low-income students, special education students and homeless students.

The state defines chronic absenteeism as missing 10 percent or more of all school days equaling 18 days a year, or two or more days per month.

In the Central Valley School district, 18.8 percent of students are chronically absent, according to state data. Statewide the rate is 16.7 percent.

Addressing absenteeism can be complicated. The reasons students miss school vary, and often touch on deeper problems, like poverty or mental illness.

Statewide, 21.9 percent of all low-income students are chronically absent. In Central Valley, that number is 24.5 percent.

“I’m always concerned about how poverty plays a huge role in all parts of academic excellence,” said Travis Schulhauser, the director of assessment and program effectiveness for Spokane Public Schools.

For instance, poorer students in Spokane Public Schools are suspended more often than their wealthier classmates, district data revealed earlier this year. Some students miss school because their families don’t have an alarm clock. Or because the students are expected to get their younger sibling ready for school. Or because the student doesn’t feel successful.

According to OSPI data, 17 percent of all Spokane Public School students are chronically absent. Meanwhile, 22.9 percent of all low-income students, 23.8 percent of special education students and 34.8 percent of homeless students are chronically absent.

“Every single kid misses school for different reasons,” Schulhauser said.

In Spokane and in Central Valley, officials have partnered with other community organizations and resources to get at the multifaceted reasons for chronic skipping. Both districts have truancy boards that meet with parents and students.

“You know that there is no way we can educate all of the kids in the Spokane area by ourselves,” Schulhauser said. “We need support.”

In Spokane, that support has come from organizations like the Hillyard Youth Collaborative, the Truancy Board and the Communities in Schools organization.

Additionally, Spokane Public Schools built an early-warning system which tracks, among other things, attendance. Community partners can gain access to those metrics with parental consent.

Schulhauser said Spokane Public Schools zooms in on the data more than the state did. Instead of looking simply at raw numbers, the district looks at students at different levels of absenteeism. That’s because a student who misses school 60 percent of the time needs different support than a student who misses school only 10 percent of the time.

“The bigger issue is unexcused absences, whereas the chronic absence thing is looking at all attendance codes,” he said of the data.

Central Valley’s approach to chronic absenteeism is similar, said Terrie VanderWegen, assistant superintendent for learning and teaching. Like Spokane Public Schools, the Central Valley District partners with other community organizations to offer wrap-around care – providing shelter, nutrition or childcare, for instance – for students and families.

“What are some resources that we can provide to the schools?” VanderWegen asked. “What are some resources we can provide to parents?”

VanderWegen said the state’s data wasn’t surprising, but it will allow the district to “drill deeper in each of these areas.”

Scott, the counselor at McDonald Elementary, said a lot of her work revolves around encouraging and keeping students in school. It hasn’t always been that way.

“It’s new to me in the last six years,” she said. “It’s been on my radar and on my heart, I guess.”