Book World: Baldwin wields the pen against his own soul

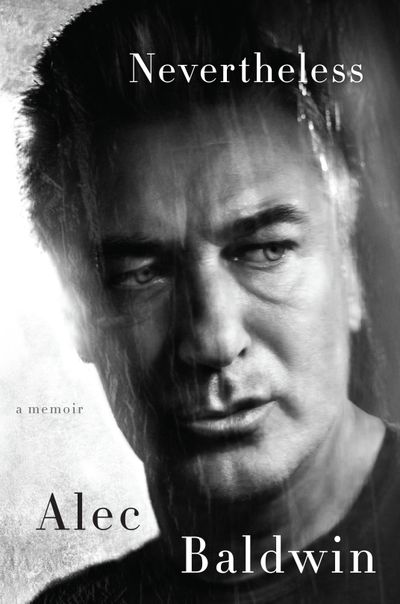

The portrait on the cover of Alec Baldwin’s new memoir does not show a celebrity basking in the glow of a long and lustrous career. It shows a man who is haunted. Instead of seducing the reader with his cool blue eyes and trademark smirk, Baldwin is looking away and askance, brow knit, as if he’s troubled by the mere existence of his book. The portrait is a fitting introduction and an appropriate warning. If Baldwin’s “Nevertheless” had a subtitle, it would be “A Portrait of the Artist as a Defeated Egotist.”

After nearly four decades in the spotlight, Alexander Baldwin III is something of an American treasure: an entertainer beloved by the public, in multiple media and genres, a step below Pacino and Nicholson in esteem, but rich, famous and talented nonetheless. He was the first Stanley Kowalski to dispel the ghost of Brando from the mind of Frank Rich. His seven-year run on the NBC sitcom “30 Rock” should be ranked alongside the work of Bob Newhart, Carroll O’Connor and Dick Van Dyke. Baldwin, a celebrity factotum, is equally adept at playing himself. He’s currently hosting both a game show on ABC and a podcast produced by WNYC. He is the voice of the New York Philharmonic. A committed Democratic activist, he was urged over the years to run for Congress, mayor or governor of New York and has been merciless in his impersonation of President Trump on “Saturday Night Live,” which he has hosted more times than anyone else. Baldwin has surmounted scandal and heartbreak to find domestic bliss, with his second wife, and a professional rhythm that has put him on-screen with Cate Blanchett, Julianne Moore and Meryl Streep.

And yet Alec Baldwin daydreams about living a different life. He wants to be the proprietor of a stationery store so he can sell “exquisite pens.” He wants to be a lawyer, a club owner, a clockmaker, the warden of a prison and a gallerist in Chelsea. Depends on the day, he writes in his preface. What’s consistent is Baldwin’s dissatisfaction with himself and his life. “Nevertheless” is a blunt object wielded by a man of sharp intellect against his own soul.

“I’m not actually writing this book to discuss my work, my opinions, or my life,” Baldwin says, three pages in, winding up for self-flagellation. “I’m writing it because I was paid to write it.”

He was probably dissatisfied by the pay, too. This rude honesty actually works in the book’s favor. It’s refreshing to read a celebrity memoir that is not painted in pastels and glossed with self-actualization, that does not ride off into the sunset after rewarding projects and hurdled obstacles. “Nevertheless,” because of Baldwin’s aimlessness, is many things: the confession of an Irish Catholic hothead, an appreciation of film and theater by a sincere aesthete, and a 265-page therapy session – wherein the reader becomes an armchair psychoanalyst unable to treat his patient.

The book starts on a promising note, with an evocative first chapter that reads almost like literature. Baldwin seems ready to emulate Patti Smith, whose “Just Kids” dispensed with simplistic autobiography and aimed for something fragmented, ethereal and truer.

“I was nine years old and addicted to solitude,” Baldwin writes in the first chapter, after drawing a sketch of his afflicted mother. By the time he describes his grandfather as “a philatelist and a numismatist,” the author’s prickly erudition is in charge, for better or worse, as he scurries along the contours of his life. He compares Jennifer Jason Leigh’s acting style to Paul Muni’s, and Anthony Hopkins’ voice to the French horn solo from Tchaikovsky’s Fifth Symphony. Baldwin’s gripping description of a cocaine overdose during his “Knots Landing” days is a high point (pun intended), and the book provides extensive evidence that fame is less a dream and more a chronic condition. That Baldwin is both enraptured and besieged by his own celebrity is what makes him fascinating and combustible; the book itself is only occasionally so. Instead, it is elegant and petty, sometimes on the same page.

Baldwin’s tortuous relationship with Kim Basinger was a significant part of his life, but it makes for a boring story when spread over dozens of pages. Same with that 2007 episode where Baldwin left his daughter a vicious voice mail that was leaked to the public. By its last third, “Nevertheless” is checking boxes instead of leaping from and around them – which is a shame, because Baldwin is a fierce wit and proven raconteur. The author humbly accepts responsibility for his personal and professional failures but uses far too much ink to taunt and settle scores. His targets include NBC, MSNBC, Harrison Ford, TMZ founder Harvey Levin, New York Times theater critic Ben Brantley, Twitter, paparazzi, the Supreme Court justices John G. Roberts Jr. and Antonin Scalia, the New York Post, Basinger’s legal team, New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio, and, of course, Trump, who has provided Baldwin with a recent booster shot of notoriety.

The third-to-last chapter seems ripped from a different book – a book that a political aspirant would publish as a trial balloon. “Campaign finance reform is the linchpin of nearly every problem we face as a nation,” Baldwin writes, and it’s here that an editor should’ve told him “Forget that. What about your relationship to God, which you’ve only hinted at thus far? And let’s address your Salieri complex head-on. How do you do meaningful work when you’re smart enough to know you’re not good enough?”

Baldwin’s memoir is readable but not memorable, a satisfactory attempt by a man who is capable of more and better. He would probably be the first to tell you that.