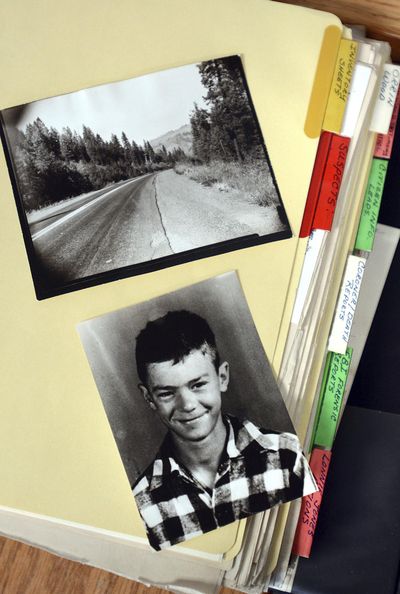

Who killed Lonnie Jones?

OROFINO, Idaho – Early on the morning of Sept. 27, 1951, Orrin C. Wood, a logger from Weippe, was headed to work at Orofino along U.S. Highway 12 when he stopped by the roadside to relieve himself.

Wood walked about 15 feet over the bank when he made a horrifying discovery.

The body of a young boy, bent over in a kneeling position with his throat slit from ear to ear and his hands positioned behind his back as if he had been bound, was lying in the weeds. The boy, Lonnie Jones, whose 13th birthday would have been Nov. 1, had been missing for four days, last seen after leaving the Clearwater County Fair.

Now 65 years since the discovery, it remains the only unsolved documented murder case in Clearwater County. Nearly everyone associated with the investigation is dead, but the story continues to haunt many residents who remember hearing about it since their youth.

During a coroner’s inquest at the Clearwater County Courthouse, conducted two days after the body was discovered, Wood described the scene.

“Well, I just was driving down the highway coming down and I got the cramps and I had to stop and I pulled over to the side to stop, never thought a thing about it, and got out and started down over the bank there and there it was,” Wood told the coroner, W.E. Gilbert.

“A body,” Wood continued. “I was pretty near on top of it before I seen it, started down over the bank there and was taking my pants down.”

Wood, who later became the prime suspect in the case but was never charged, rushed to Orofino to alert the sheriff.

Boy last seen after midnight hitchhiking home from the fair

Jones lived with his grandmother, Ethel Spence in Weippe. The two of them had been at the fair on Saturday, Sept. 23, but about 3:30 p.m., Spence wanted to return home.

Jones pleaded to be allowed to stay.

“He said, ‘Why can’t I stay?’” Spence told the coroner’s jury. “I said, ‘Well, you have been down here all day and you will want to come back tomorrow.’ And he kind of stood there and he said, ‘Why can’t I?’ I didn’t answer him and he said, ‘I saw Tommy.’ He came down with (Tommy) Jared’s people in the morning. ‘I seen Tommy and they said they would be going back after a while.’”

Spence finally agreed to let her grandson remain at the fair, believing he could catch a ride home. She gave him a dollar and then reminded him: “Lonnie, you remember that if you miss your ride, you will have to walk home.”

Shortly after midnight, two young men from Kamiah, Leroy Kidder, 19, and Bob Hill, 17, were returning home after dropping off their dates and spied a young boy hitchhiking at the end of the Orofino bridge.

It was Jones, and he asked for a ride to the Greer bridge, about 7 miles upstream.

Kidder said Jones got into the front seat and the three of them chatted casually about the fair and people they knew.

When they let Jones out at the bridge, Kidder told the coroner’s jury, the boy seemed cheerful and confident he could find a ride the rest of the way up the grade to Weippe. There were cars coming in both directions, Kidder noted.

Two days later, Kidder and Hill read in the newspaper that Jones was missing.

Kidder, now 84 and living in Lewiston, said they contacted the sheriff’s office and were asked to come to Orofino to identify the boy. At the time, Kidder said during an interview recently, he didn’t realize Jones was dead.

“Like a dumb kid, I thought they’d found him,” Kidder said.

Sheriff V.L. “Slim” Holloway immediately launched a manhunt for the killer. Later, a retired FBI agent, Henry Savage of Colfax, was brought into the investigation.

Several suspects, including Wood, were rounded up and brought in for questioning.

Minimal documentation and clues remains from 65-year-old case

Clearwater County Sheriff’s Department Detective Mitch Jared, son of Tommy Jared and the investigator who has been in charge of the case since 2004, said there appears to have been no strong evidence that any of the suspects were linked to the crime, other than the belief they were homosexual.

An old newspaper report from the Lewiston Tribune said Jones’ body was nude and that he had been sexually assaulted.

Photographs of the crime scene show that when Jones was found, he was wearing clothes. An autopsy revealed he had a full stomach at the time of his death. But Jared said he has uncovered no evidence to support the claim the boy had been molested.

Documentation from the 65-year-old case, however, is sparse. A large binder containing transcripts of interviews with the suspects and others that are kept in a small cardboard box are the only remaining clues.

There may be other records somewhere, Jared said, “but I don’t have access to them. They’re not here.

“When I look in there, I can see things were sent to the FBI, but we don’t have those things. I thought we might be able to send something off for DNA testing, but there’s nothing to send. They had nothing or couldn’t find anything about the case,” Jared said.

All of the people who were involved in the original investigation, Jared said, are dead.

“This occurred in 1951 and we’re so many generations removed from it that I can’t seem to find anybody that knows anything about it.

“This is the only (case) that we have that is unsolved and that we have case files and photos and a few things of evidence,” Jared said. “But even the few things of evidence that we have are not really described where I can tell where they got them. There’s just no chain of evidence it’s just more an item laying in a box.”

Back in 1951, at the coroner’s inquest, Jones’ grandmother told the jury that when her grandson failed to show up at home the next morning, she returned to the fair and began looking for him.

Jones had reportedly attended a movie with some friends and the next time he was seen was when he was picked up at the end of the bridge by Kidder and Hill.

Kidder said through the years he and his friend, Hill, talked about the mystery many times and wished they had acted differently.

But for a while, Kidder and Hill had problems of their own. They realized they were suspects when they noticed they were being tailed by someone watching their movements. They also thought the murderer might be after them.

“We were two scared-to-death kids,” he said. When they were called before the coroner’s jury, the Kamiah chief of police “talked to us and said, ‘You boys want to listen real carefully through the questions. Don’t answer questions you’re not sure of because they will mix them up for you a little.’

“We got by fine and after the inquest they backed off from us,” Kidder said.

“Bob and I wished we had went on to Weippe with him, but there were a lot of people (coming and going) and the boy said there will be people by to pick him up.

“So us, not thinking, we let him off at the end of the bridge. We drove off and about Monday morning, it come out in the paper that Lonnie Jones was missing.”

Detective Jared said he remembers his father and grandmother talking about the case when he was young.

“It was a story we heard about,” Jared said. “I know my dad talks about … (how) it really scared the kids because nothing like this had ever happened to one of their own.”