Idaho icon Cecil Andrus reflects on career that helped shape the state

When Cecil Andrus closed Idaho’s borders to nuclear waste, the former Democratic governor’s decisive action captured the attention of the nation and put pressure on the federal government to remove long-stored waste from a nuclear research complex near Idaho Falls.

“Did I have the authority to do that? No, I did not,” Andrus said with a grin. “… But the federal government flinched.”

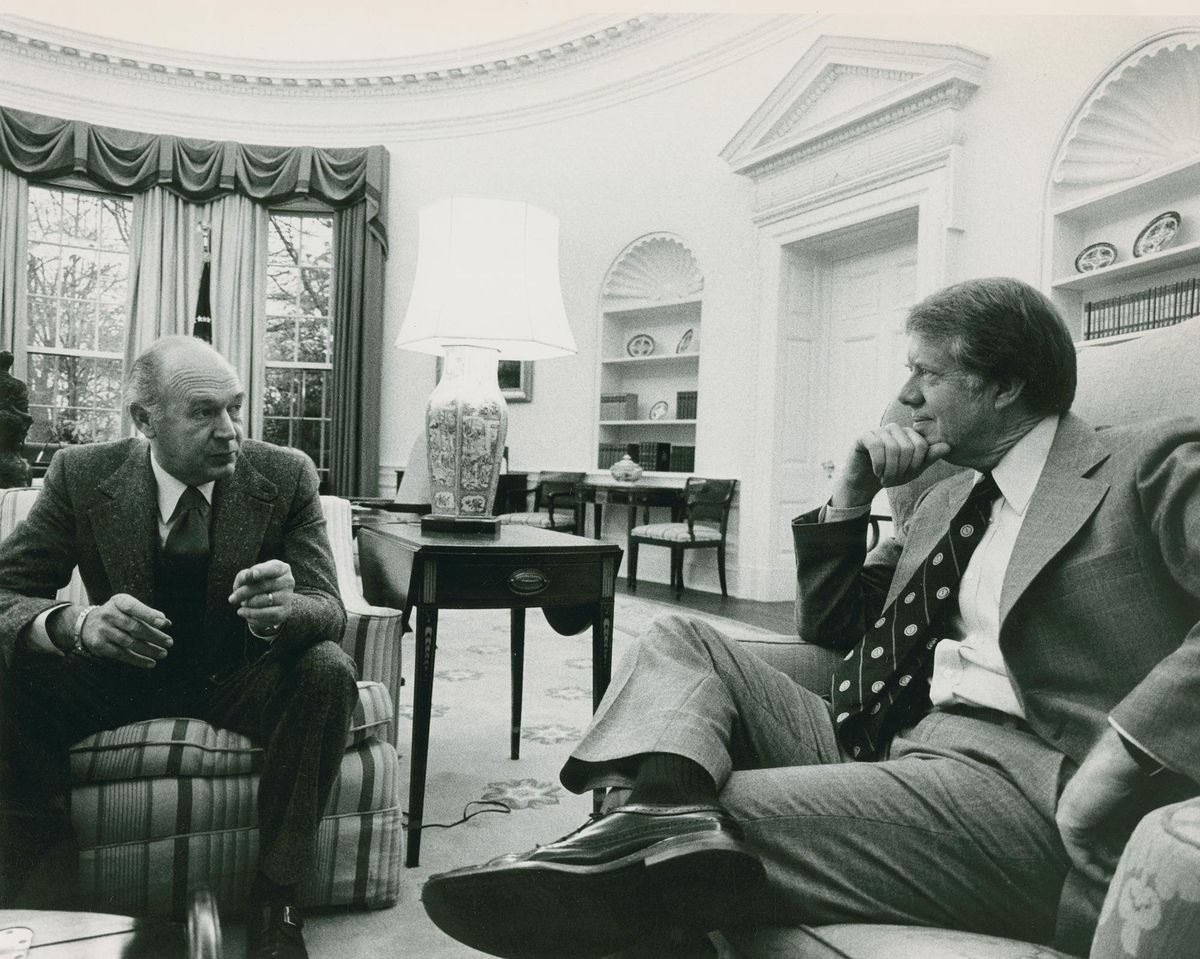

The last Democrat to lead deep-red Idaho, Andrus was elected to four terms as governor, interrupted by a four-year Cabinet post as Interior secretary under Jimmy Carter. He’s 85 now, and as he reflects on his career, the nuclear waste showdown looms large – mainly because it’s not over yet.

A 1995 agreement signed by the feds and Gov. Phil Batt, and subsequent court cases, call for all radioactive waste to be removed from the Idaho National Laboratory by 2035. The eastern Idaho site stands above an aquifer serving half the state’s population and millions of acres of irrigated cropland.

“If something happened to the quality of that water … you couldn’t sell an Idaho baked potato anyplace in the world, because it would be radioactive,” Andrus said.

“I’ve promised some of those people over there at INL that I’m going to live past my 100th birthday in order to see that they’ve got it cleaned up by 2035,” he said. “They’re going to have to put up with me for quite a while.”

Andrus’ career is unique in the GOP-dominated Gem State. When first elected governor in 1970, he was the first Democrat in that post in 24 years. Democrats controlled the governorship for the next 24 years, until Batt succeeded Andrus in 1994.

An Orofino lumberjack spurred to run by concerns over the local schools, Andrus became an Idaho icon. After big fights, he brought kindergarten to Idaho and increased school funding. He halted a major coal power plant proposed near Boise and engineered protection of Idaho’s famed wilderness areas.

“He’s one of the giants of Idaho politics and one of the most effective governors in Idaho history,” said longtime political observer Jim Weatherby, an emeritus professor at Boise State University. “His priorities were clear. … Andrus was a strong leader who also knew the fine art of compromise.”

Idaho not a dump site

As a state senator from Orofino in the 1960s, Andrus said, “I didn’t know nuclear waste, period.” But then he took a tour of the High Desert Idaho National Lab site and was shocked by the “indiscriminate dumping” right over the largest freshwater aquifer in the nation.

“They just took a bulldozer during the late ’40s and ’50s and dug trenches out there in the sand,” he said.

The federal government called it “interim storage.”

When Andrus was in his first term as governor in 1973, troubling rumblings began in Washington, D.C., about Idaho becoming the nation’s long-term repository for nuclear waste. Andrus and Idaho Sen. Frank Church, also a Democrat, fired off a telegram to the head of the Atomic Energy Commission, Dixy Lee Ray – later the governor of Washington – demanding the waste be “removed for permanent storage at the earliest possible date.”

“She wrote me back a letter, which is in the archives, saying, ‘Oh, governor, we’ll take care of that right away – it’ll all be gone by the end of this decade’ – the decade of the ’70s,” Andrus said.

Ray’s letter, received by the Idaho governor’s office on Nov. 9, 1973, said in part, “I can assure you that the (Idaho lab site) is not being considered in any way as the site for permanent disposal of any long-lived nuclear waste.”

“There was no effort whatsoever on the part of the federal government to clean up the mess,” Andrus said.

After leading the Interior Department, Andrus came home and went into private practice. He was elected governor again in 1986. “And I took a look – not one damn thing had been done” about the nuclear waste, he said.

Part of his work as Interior secretary included overseeing creation of the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant at Carlsbad, New Mexico, which was supposed to be the nation’s long-term nuclear waste storage site. In 1988, he flew to New Mexico for one of the final inspections of the plant.

“We’re flying home, and I said, well, the WIPP site is ready to accept it – we’ve got to get the federal government’s attention,” he said. Andrus decided, “I am closing the borders of the state of Idaho to any importation of nuclear waste.”

His press secretary, Marc Johnson, questioned whether he could do that. Andrus replied, “I want a state police car parked across the railroad tracks, and the train will not deliver any of that garbage to Idaho. We’re through being the dump for the world.”

The trooper assigned to guard the stalled boxcar of radioactive waste at a holding yard in Blackfoot “was a man who had biceps that were larger than my thigh, and he had on a short-sleeved shirt,” Andrus said. “And here he is standing by his patrol car across the railroad track, and a photographer who is a stringer for the New York Times took a picture of him.”

A heroic stand

The photo ran in the Sunday Times on Oct. 23, 1988, over the headline, “Idaho Firm on Barring Atomic Waste.” More headlines followed, Congress took note and “all of a sudden, we had leverage,” Andrus said.

“They had to hook up to the next train that went the other way, back to Colorado,” he said. “And there was litigation, which we won.”

In the Andrus Archives at Boise State University, three file folders are stuffed with thousands of handwritten and typed letters and phone messages from citizens throughout Idaho and all over the nation lauding Andrus for his stand against the waste. They range from a note from an 11-year-old boy to messages from business leaders, philanthropist Velma Morrison and others.

“If Idaho is too great to litter, then surely it is too great to be a dump,” wrote Judith Dvorak of Aberdeen.

Then-state Sen. Marguerite McLaughlin, D-Orofino, wrote, “Politically, even the Republicans around here are impressed, and I hear only positive comments.”

John and Kathy Lung of Boise told him, “Courage is a rare commodity, and you are to be congratulated on taking such a courageous stand.”

“I have added you to my small and very select list of heroes,” one woman wrote.

Andrus, in a letter to U.S. Secretary of Energy John S. Herrington, wrote, “We have accepted too many promises that simply have not been kept. We must have a solution that moves waste from Idaho.”

After the Batt agreement, U.S. District Judge Edward Lodge famously ruled that “all means all” on removing the waste.

“Then they got serious with cleaning up the waste and have made great progress,” Andrus said. “But there’s still a lot more to do.”

Four decaying steel tanks of liquid waste remain buried over the aquifer.

“If we had a leak, the worst-case scenarios … would take place immediately,” he said, snapping his fingers. “They’re single-wall stainless steel. They’ve been there over 50 years. Is the good Lord just being nice to us and there’s no leaks? Or did they start to leak yesterday or last night or tomorrow? I don’t know. Phil Batt and I have decided that is the most dangerous thing.”

Andrus and Batt have spoken out against moves by current Gov. Butch Otter to waive the 1995 agreement and allow new spent nuclear fuel shipments to come in for research before the liquid waste tanks are removed.

‘A cold day in hell’

It was education – concerns about the local schools as his oldest daughter started elementary school – that first got Andrus into politics. He served four terms in the state Senate before his first run for governor in 1966.

Andrus lost the primary to Charles Herndon, who then died in a plane crash. Andrus became the Democratic nominee but lost the general election.

“I’m the only person in America that has run for governor twice in the same year and lost both times,” he said.

Four years later, he challenged Republican Gov. Don Samuelson and won.

“The issues were not that much different than what they are today: education and the environment in which we live, and the balance between the utilization of the resources, both in finite roles and in renewable roles,” Andrus said. “I didn’t exactly get in in a landslide – I beat him by only 10,000 votes, but 10,000 votes in Idaho that year was enough. I would’ve settled for one.”

John McMurray, chairman of Idaho’s Republican Party, had told Andrus, “It will be a cold day in hell when we elect a Democrat governor.”

Andrus said he thought about the comment on Jan. 4, 1971, when he stepped through the doors of the state Capitol to take the oath of office and give his inaugural speech.

“They opened the doors and that cold blast of air hit me and it was about 15 degrees above zero at 12 noon, and what went through my head at the time was, ‘John was right – it is a cold day.’ ”

Andrus attributes his victory to traveling the state widely and making the case that Idaho had enough revenue, but it wasn’t putting enough into education. “They kept wanting to give it away (through tax cuts), just like they are today,” he said.

His first task was to deal with a $4 million deficit in the general fund, plus $6 million in unpaid bills.

“The very first executive order that I signed was a 4 percent holdback on expenditures in every area except education,” he said, deriding the “great conservatives that preceded me.” He said, “My first job was to clean up their mess.”

Andrus said he drew on the relationships he’d built in four terms in the Senate. “In those days the margin was very close, to where I had enough experience and friends upstairs that I could go to them, we would work out situations,” he said. “There wasn’t that bitterness and rancor of partisanship that you see that prevails today.”

Education and the environment dominated his agenda as governor, both in his first two terms and his later two.

“There were only two states in America that didn’t have kindergartens, and it was Mississippi and Idaho,” he said. “We were tied for last. But it took me five sessions of the Legislature to get it passed.”

“We were also increasing the funding for 1-12 – now it’s K-12,” he said. He recalled Idaho teachers taking jobs across the state line and commuting because the pay was so much higher elsewhere. “If you want good teachers, you’ve got to compete.”

Returning NRA snub

Andrus went toe-to-toe with Idaho Power Co. – which some in the early 1970s joked was so powerful the state had been named after it – to halt a proposed coal-burning power plant 30 miles from the Capitol. In addition to serious health and economic concerns, the proposed plant would have “made Boise a far less attractive place to live,” he said.

Wilderness designations have been landmarks of Andrus’ career, including fighting against logging interests to establish the Frank Church-River of No Return Wilderness.

Andrus has always been an avid outdoorsman, and he has collected and used firearms for decades.

“I have hunted and fished every year, all my life, and I still do,” he said. “Now the mountains are getting a little steeper and some places I don’t go that I used to go. But in 1986, I was still very, very active.”

That’s the year he ran for his third term as governor. “And my opponent was an attorney that never had a hunting and fishing license in his life, didn’t have a firearm.” Yet the National Rifle Association endorsed his opponent.

“We did battle, and I have to this day disagreed vehemently with their position on guns – that anything goes,” he said.

After his victory, Andrus recalled, “I get a letter from the NRA saying, ‘Oh, congratulations on your victory, we look forward to working closely with you.’ I don’t know what made me do it, but I got that letter and I just scrawled across it ‘Don’t bet on it!’, put it in an envelope and mailed it.”

Four years later, when Andrus was running for governor a fourth time, the letter – with his scrawled remark – resurfaced in the campaign. But he won again.

“The NRA, I referred to them as ‘gun nuts’ and a few things that inflamed the controversy,” he said.

Andrus said the NRA endorsed his opponent, David Leroy, solely because Leroy was a Republican.

“That was the difference,” he said. “The NRA in Idaho were conservationists, Democrats and Republicans alike, I mean, a mixture. It was conservation and hunting and fishing we cared about. We didn’t care about whether you were a donkey or an elephant. But at the national level, the NRA has always been a right-wing Republican group, and they haven’t changed.”

The NRA saw its membership decline in Idaho that year, he said. “A lot of my friends mailed in their cards.”

Not happy with today’s political climate

Andrus isn’t happy about today’s politics. He attributes the decline in Idaho’s Democratic Party over the years partly to President Bill Clinton, whom he calls “Slick Willie.”

“Some of the issues that came up during his tenure were not helpful to the Western United States,” he said.

Environmental initiatives especially backfired politically, “and the Republicans were a lot smarter than we Democrats, and Phil Batt did a great job as chairman for the party,” Andrus said.

In 1992, Batt held meetings in all 44 counties and built the party structure that endures today. Republicans now hold every statewide office in Idaho, the entire congressional delegation and 80 percent of the seats in the Legislature.

“Their organization and financing far outstripped the Democrats, and that’s the Democrats’ fault,” Andrus said.

He has observed the current splits in Idaho’s Republican Party with some amusement, saying, “It couldn’t happen to a nicer bunch of people – it’s about time. We Democrats have a history of fighting among ourselves.”

Andrus said it’s worse in D.C. “Pettiness, bitterness, rancor, partisan activities abound, and both parties are guilty. … I’m not pulling my donkey hat on; I’m critical of both of them.”

His solution: term limits. “Absolutely – two terms for a senator and an equal number of years (12) for a House member, and psshht, they’re done forever,” he said.

But Andrus doesn’t expect Congress would enact limits.

And with his donkey hat on, Andrus backs Hillary Clinton for president.

“I want to see a woman president of the United States,” he said. “She is the candidate, and I’d like to see her elected.”