Ailene Voisin: Bill Walton still trucking, healthy

Big men and bad feet go together like, well, Lennon and McCartney. The list of NBA centers who retired prematurely or spent time on the disabled list because of ankle or foot problems includes Yao Ming, Marc Gasol, Joel Embiid, Brook Lopez, Zydrunas Ilgauskas, Andrew Bogut and DeMarcus Cousins.

But the definitive book on bad feet – how they can cripple a career and damage the soul – recently was written by Bill Walton, a complex, fascinating character who could have become the game’s greatest center if not betrayed by his own two feet.

The navicular bone broke again and again. It broke his heart more times than he can count.

In 14 NBA seasons, Walton finished only two. Since his early teens, he has had 37 orthopedic surgeries, most on his malformed feet.

“My feet were not built to last, or to play basketball,” the Hall of Famer writes in his new autobiography, “Bill Walton: Back from the Dead.”

“My skeletal, structural foundation – inflexible and rigid – could not absorb the endless stress and impact of running, jumping, turning, twisting, and pounding for 26 years.”

But Walton, 63, keeps on trucking. His memoir is a delightful and compelling read, a chronicle of the competing loves of his life – basketball, music and his bike – and how each factored into his most memorable moments, as well as his recovery from a near-suicidal descent caused by relentless, excruciating spinal pain.

While the book is upbeat, insightful and inspiring, true to the nature of the irrepressible, loquacious author, it also is a cautionary tale for modern athletes whose careers are largely dictated by variables such as size, weight, height, desire and playing for the right coach and the right team at the right time. If many of Walton’s injuries are attributable to his poor genetics, the numbers suggest that 7-footers increasingly function in the danger zone.

“The pool of big men is much smaller,” Walton said recently. “If you look at guys like Hakeem Olajuwon, David Robinson, Patrick Ewing, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, their feet didn’t seem to bother them. I’m the poster boy for the wrong end of the spectrum. I tore up my knee when I was 14, and nothing was ever the same.”

And what of Yao, Bogut, Cousins, Embiid, Gasol, Ilgauskas, Lopez, not to mention the great Lithuanian Arvydas Sabonis?

Walton, a voracious reader and researcher who could have written a thesis on the navicular, has theories, suspicions, deep-rooted beliefs about today’s big men and why so many suffer foot injuries and/or lingering ankle discomfort Cousins has complained about the past two seasons. Other than genetics, Walton cites overuse – the AAU circuit and year-round play – and poor conditioning.

“I’m the biggest believer in the world of physical fitness,” said Walton, a San Diego native who preferred to be listed at 6-foot-11 but was widely believed to be 7-feet plus. “I’m a product of the John Wooden school of basketball. That’s running. That’s nutrition and your lifestyle choices. The most I ever weighed was 242, and that was at the end of my career in Boston. I mostly weighed 232 to 237, depending on who I was mostly matched up against. If I was going to play Kareem, I’d be 235. If it was Artis Gilmore, I’d get up to 237. For Dave Cowens, I would get down to 232.”

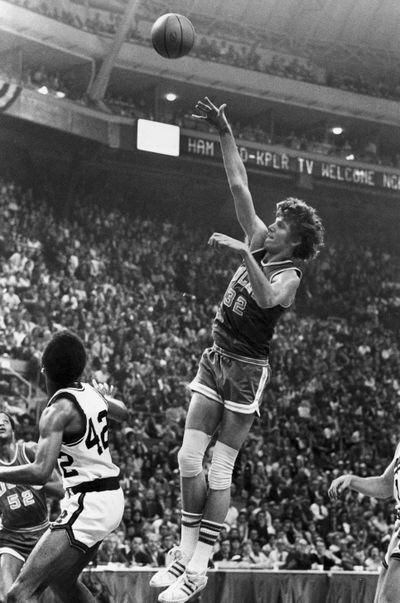

Despite the brevity of his career, he was dominant on and off the court. He was a three-time college Player of the Year at UCLA, a two-time NCAA champion, a two-time NBA champion (Portland, Boston), an NBA MVP, one of the 50 greatest players in NBA history and a member of the Naismith Hall of Fame.

He was feared by opponents even when he didn’t play. True story: While recovering from another foot surgery early in his tenure with the Clippers (1979-85), Walton enrolled at Stanford Law School and occasionally played the weekend games in San Diego. Once, his former Trail Blazers coach, Jack Ramsay, dispatched assistant Jim Lynam to San Diego to snoop around about Walton’s upcoming schedule.

Walton didn’t disappoint. He flew home for the game against his former team, put on his Clippers uniform and dominated. Ramsay afterward sat alone in the stands, almost in a daze, remembering what was, and sadly what might have been: The redhead was the complete package, a basketball savant who led the league in rebounding and blocked shots, scored with either hand, and was a superb playmaker who enjoyed throwing the perfect outlet pass even more than he loved his music, his beach, and later his bike.

“I had such big dreams, you know?” Walton said. “I came so close, and every time my body would fail me. My life is a story of hope and despair, of success and catastrophic failure. But then when you are in so much pain that you think you are going to die? And then you find someone, Dr. Steve Garfin, who saves your life? I’m alive today because of his surgery and his medical people.”

While getting off a plane after an assignment for ESPN in February 2009, Walton collapsed. Close friend Jim Gray was referred to Garfin, a UC San Diego orthopedic surgeon. Following an innovative operation on his spine – and months of grueling rehabilitation – Walton regained much of his mobility. Though he can no longer hike or walk for extended periods, he cycles for hours. He also returned to ESPN as a Pacific-12 Conference analyst and does radio for Westwood One.

“I haven’t been this healthy since I was 13,” Walton said. “I have no pain. I take no medication. I work on spine health and strengthening my core muscles. And I have a wife I love (Lori) and four boys, including Luke. How great is it to be able to watch Luke follow his dreams (as the Lakers’ new coach)? That’s why I wanted to write this book. People have written books about me, but I wrote this myself. It’s about chasing a dream, listening to Jerry Garcia, having Chick Hearn in my ear, and John Wooden in my life. I’m so lucky, really, and loving life.”