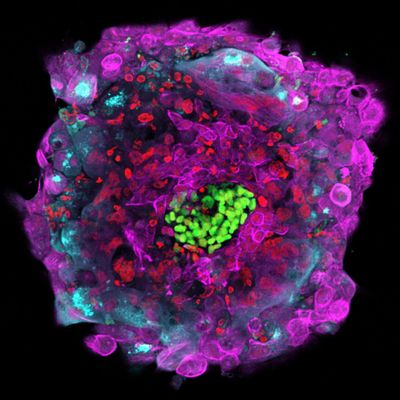

Early embryo development seen with aid of new lab techniques

NEW YORK – New lab techniques have provided the first good look at a crucial but mysterious stage in the development of human embryos, scientists reported Wednesday.

The researchers said follow-up research might eventually lead to new treatments for infertility and perhaps new forms of birth control.

The work extends the amount of embryonic development that can be observed in a laboratory.

In the first week after fertilization, an egg grows into a hollow ball of cells, and scientists have long been able to watch that happen. But then this early embryo – about the size of a grain of salt – attaches itself to a woman’s uterus and undergoes radical change, and that stage has been a “complete black box,” said Ali Brivanlou of Rockefeller University in New York.

He’s a member of one of two scientific teams that reported on Monday that they were able to extend embryonic development into a second week in a lab dish. Neither team simulated implantation, because the embryos attached themselves to the plastic of lab dishes rather than to uterine tissue.

But even without any direction from a mother, the embryos proceeded with critical steps toward making a body. They flattened into disks, which then assumed a volcano-like shape. They produced primitive internal structures and specialized cells. Brivanlou’s team spotted an unexpected type of cell that he said had not been detected in any other mammal species. Researchers have “no clue” what it does, he said.

“We can now ask how the fundamental structures of the embryo are formed after implantation,” said Magdalena Zernicka-Goetz of Cambridge University in England, who led the second team.

Both groups worked independently to modify a lab technique Zernicka-Goetz’s lab had developed for working with mouse embryos. Brivanlou and colleagues reported results in the journal Nature, while Zernicka-Goetz’s team reported in Nature Cell Biology. Both teams used embryos donated by couples who’d used fertility clinics.

Brivanlou’s team terminated its research at the embryonic stage corresponding to 14 days after fertilization, and Zernicka-Goetz’s experiments were stopped on days 12 or 13. That’s because of the “14-day rule,” an international ethical standard that limits laboratory studies of human embryos.

Experts not involved in the research were impressed by the results.

The “beautiful work” provides new ways to look at how early embryos develop, said reproductive biologist Bruce Murphy, a University of Montreal researcher who is president of the Society for the Study of Reproduction.

“You’re seeing the way cells begin to organize in the very early stages of producing a new baby, and that is fascinating for anybody,” said John Aplin of the University of Manchester in England.

“It gives us all kinds of new ideas to work on,” said D. Randall Armant of Wayne State University in Detroit.