Teton Dam collapse 40 years ago was worst man-made disaster in Idaho history

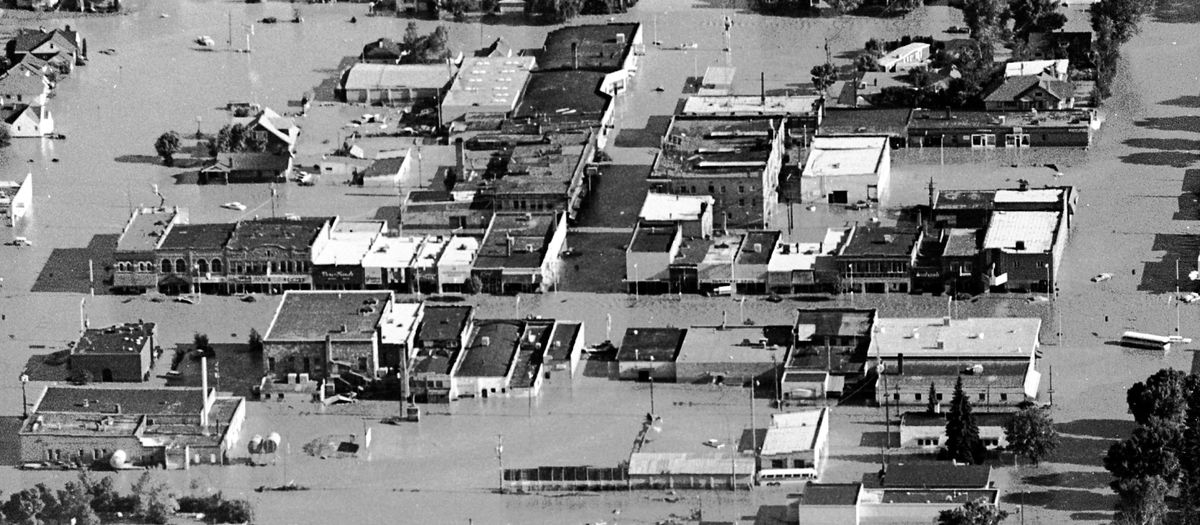

Cleaning up Sugar City after the Teton Flood in June 1976. (Robert Bower / (Idaho Falls) Post Register archive)

Forty years ago today, the Teton Dam collapsed, triggering a disaster the likes of which eastern Idaho had never seen before. Those who lived through it recall the chaos. At first, many didn’t believe the reports they were hearing were true.

Phone lines were knocked out. Highways were blocked. What eastern Idaho residents heard on June 5, 1976, over the only reliable form of immediate communication – the radio airwaves – was incomprehensible.

“The dam has busted,” Don Ellis said on Rexburg station KRXK.

As the world soon learned, the 305-foot-high Teton Dam had broken in half. Its collapse sent a wall of water cascading through the Teton River canyon, north of the town of Newdale in Fremont County. Downstream, with no canyon to contain it, the flood fanned out for miles across the Snake River Plain. The water turned south, gobbling up cattle, cars and homes on its slow march to Idaho Falls and beyond.

Forty years later, many eastern Idaho residents vividly recall the chaos set in motion that sunny Saturday morning. Eleven people died and thousands more were displaced in the flood, considered the worst man-made disaster in Idaho history. Crops were ruined and thousands of cattle were killed. Total damage estimates hit up to $2 billion — $8.4 billion in today’s dollars.

And almost nobody saw it coming. In fact, when most people heard initial reports of the collapse, they refused to believe it.

“Naturally, I thought it was a hoax of some kind,” said John C. Porter, then-mayor of Rexburg, in an LDS church oral history. “We had lived in the shadows of dams for years in Idaho, and nothing had ever happened.”

On the scene of the collapse

The Teton Dam had been finished for less than a year when it collapsed. Its 17-mile-long reservoir was nearly full.

The U.S. Bureau of Reclamation billed the dam project as a way to control spring runoff and offer more consistent water supply to farmers during the summer months. Instead, it caused chaos.

The first hints of trouble came as the new reservoir continued to fill in the early days of June. An inspection team on June 3 noticed water seeping from the ground at several locations downstream from the dam. At 7 a.m. June 5, the day of the collapse, workers noticed the first seep on the dam face itself. By mid-morning, a large wet spot had formed.

Jay Calderwood, a heavy equipment operator, helped build the dam. At 10:30 a.m. on June 5 he got a call at his home in Victor, Idaho. After racing to the scene, he drove a bulldozer onto the top of the dam to try and stem the leaking, according to an account he gave later for the Teton Oral History Program, a joint effort to document the disaster by Ricks College, Utah State University and several foundations.

“I don’t think we can stop it,” Calderwood remembered thinking.

But he tried. A massive whirlpool had formed next to the dam, the water disappearing far beneath them. Along with other workers, Calderwood pushed boulders into the whirlpool to try to plug the breach. Then they felt the dam shift beneath their tractors.

“We were backing across the dam and had the dozers in reverse when the dam fell through,” he said. “It caved right in front of us. While we were backing away, we kept thinking it was going to cave behind us and take us with it. But it never did.”

The man who rode the flood

Perhaps nobody had a closer view of the flood than Daryl Wayne Grigg, a sawmill worker from St. Anthony. Grigg recounted his story in 1977 for the Teton Oral History Program.

When the dam broke, Grigg was with his friend David Benson. They were fishing on a small island in the Teton River about two miles below the dam, a place they had visited many times before. “It was pretty good fishing,” Grigg said.

Grigg and Benson had just set foot on the island when they noticed an airplane flying low overhead. The pilot was waving at them. They didn’t recognize him but figured maybe they knew him. They waved back.

Suddenly, the river rose by six feet. Grigg looked upstream and saw a 30-foot-tall wall of water crashing down the canyon.

“I turned and yelled at David, telling him to jump in the river,” Grigg told the Oral History Program. “That is what I did. We started swimming, but that didn’t work. That was the last time I have seen David.”

After a long struggle, Grigg popped to the surface of the raging torrent. He grabbed a log to stay afloat. He cussed, then prayed. “I just figured it was all over with,” he said.

As he floated downriver, Grigg heard the panicked cry of cattle and watched homes float off their foundations. His log slammed into another, breaking five of his ribs and puncturing a lung.

After a three-mile ride, Grigg managed to climb a cottonwood tree. He told the interviewer he didn’t recall much after that. After four hours in the tree, he was rescued by friends in a boat. Benson wasn’t so lucky: His body was later found about a quarter-mile from the cottonwood tree.

The interviewer asked Grigg whether he supported building the dam when its construction was being debated several years prior.

“I was for it,” Grigg said. “… But I’m opposed to it now.”

Recording the chaos from the air

In the Post-Register newsroom in Idaho Falls, word of something big at Teton Dam trickled in around noon, Robert Bower, a former staff photographer, said in an interview last week. At first, nobody was sure whether to believe the sketchy phone and radio reports, he said.

But if the dam really was collapsing, Bower didn’t want to miss the story. He chartered a private airplane from the Idaho Falls airport to ride to the scene. As Bower and the two pilots flew over Sugar City, there was no sign of floodwaters. But Bower spotted a plume of dust on the horizon.

Minutes later, as the plane took a pass over the dam itself, Bower leaned out an open window and started snapping pictures. Over the drone of the engine, he heard a secondary roar from far below – the sound of millions of gallons of water leaving the reservoir.

“The canyon was running deep with muddy water,” he said. “The scale of it was truly amazing to see.”

On the way back south, the plane caught up to the leading edge of the flood. Bower watched as the water, now several feet high, slowly engulfed fence posts, then cattle, and then Sugar City.

“It was coming fast,” he said. “And the supply behind it was ever-increasing.”

For Bower and other Post Register staffers, it was the first of many 15- to 18-hour work days covering the largest disaster the region had ever seen.

The water continues south

Sugar City was essentially annihilated. The Post Register reported that 250 homes were destroyed, and those that remained were under 10 to 12 feet of water.

Then-mayor Lyle Moon was near the dam making petroleum deliveries, when dispatchers told him of the collapse. He thought it was a joke.

“Tell me another one,” he told his dispatcher.

Another 150 homes in the city of Teton were leveled, according to Post Register reporting. Trees were uprooted and carried away.

“Total devastation,” was the way one reporter, Chris Dunagan, described it on the first day. “People are just shocked, standing around. They can’t believe what’s going on.”

Farther south, Mark G. Ricks, president of the Rexburg Stake, would later tell church historians that word of the coming flood was spread through the city by police who had loudspeakers and neighbors going door to door.

“The vast majority of people moved out with just the clothes that were on their back,” Ricks said.

Residents made their way to higher ground. They watched from the top of the Ricks College hill as brown water rolled into the city, flooding basements and sending floating houses crashing into trees. Ricks thought he might be dreaming.

“I think that most people just didn’t believe it was going to happen, and yet it was happening,” he said. “And we sat there and watched it, and still didn’t believe it was true.”

Ricks worked with the LDS Church to organize relief efforts, bringing food from church storehouses in Ucon and Salt Lake City.

The dormitories at Ricks College became temporary shelter for beleaguered residents. At one point, its cafeteria served 30,000 meals in one day.

The next day, Main Street was under five feet of water. Cleanup and recovery would take months. While hundreds of millions in reparations would by paid by the Bureau of Reclamation to the residents of Sugar City and Rexburg, it was cold comfort for many.

“We wouldn’t trade that town of Sugar City, and they wouldn’t trade their town of Rexburg, for all the money they’ve got back in Washington, D.C.,” Lyle Moon said.

A community effort in Idaho Falls

In Idaho Falls, the water wouldn’t reach its peak on the Snake River until Sunday, which gave officials and residents time to prepare. First, it rose to the point that the city’s signature waterfalls disappeared. Then, the water began to flow over the Broadway Bridge.

To save the bridge, residents took drastic measures. They cut a 40-foot wide canal through Broadway to the west of the bridge. Throughout town, residents filled sandbags to save low-lying buildings near the river.

Everybody pitched in, then-City Councilman Mel Erickson said in an interview last year. There were sandbag assembly lines, and residents brought their pickup trucks and dump trucks to help in the effort.

“It really united the town,” Erickson said.

But some things couldn’t be saved. The wall of water ruined the city’s three hydropower plants on the Snake River. The plants were eventually replaced, funded with $96 million in bond money that wasn’t paid down until last year.

One of the most famous photographs from the disaster was taken just as a wave of water breached the Broadway Bridge.

Bower said he had been standing next to the bridge for a time on June 6, watching as the water steadily rose. He sidled up to a police officer who was preventing anyone from crossing.

“I said, ‘I’ve got to go out on that bridge, and take a few pictures.’ He said, ‘I’m not supposed to let you out there, but I’ll look the other way for 30 seconds.’”

Bower ran onto the bridge as water poured over the road surface. He could feel the structure vibrating beneath his feet. “You didn’t want to stay out there,” he said.

But the risk was worth it.

“That was the picture that summed it up,” he said.

Note: Special thanks to the Special Collections Department at Brigham Young University-Idaho for access to church oral histories and Teton Oral History Project resources.