Spokane Missing Person Event lets families take action

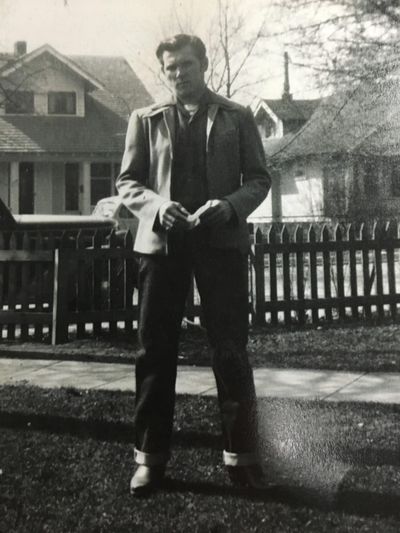

There were rumors about what happened to 21-year-old Army veteran Alvin Matlock after he vanished in 1951 – and none of them were good.

His brother Clyde was 12 when Alvin disappeared. Now 77, Clyde Matlock just wants to find his brother’s body.

“I want to find out what happened to him,” he said.

Matlock and his wife, Patricia, came to the inaugural Missing Person Event hosted by the Spokane County Medical Examiner’s Office. People could file police reports, submit DNA and dental records, and provide photographs of loved ones.

The Matlock family first knew something was wrong on Thanksgiving Day 1951, when Alvin Matlock didn’t show up for the family celebration. His upset mother drove to his cabin on Browne Mountain to find the cabin empty and his vehicles gone.

The family was told that he had packed up and gone to Alaska. Clyde Matlock believed that for a while, mostly because he wanted to. But as the years passed, it became clear that Alvin wasn’t in Alaska.

The story going around was that Alvin Matlock was having an affair with a married woman and had gotten into a fight with her husband when the two were discovered. It’s rumored that the woman shot Alvin during the scuffle.

“The story was he was crying for help and they just let him die,” Patricia Matlock said.

Police investigated, but never made an arrest.

“They didn’t have a body,” she said. “They couldn’t arrest anyone.”

Patricia Matlock has done some detective work of her own in the past few years, trying to find new leads and track down possible witnesses.

“Somebody must know something,” she said.

But on Saturday, all Clyde Matlock could do was hand over some photographs of his brother and provide his DNA in the hopes that someday his brother’s remains will be found and identified.

Families like the Matlocks now have access to the National Missing and Unidentified Persons System (NamUs) database that is also used by police and medical examiners. People can enter information about missing friends or relatives, while medical examiners can post identifying information for unidentified people who have been found dead.

Before the NamUs database existed, there was only a hodgepodge of separate, disconnected databases for missing and unidentified people, forensic pathologist Dr. Sally Aiken said.

“The databases didn’t speak to one another,” she said. “They were cumbersome. NamUs is a wonderful resource.”

Her office has used the database to identify three people who couldn’t be easily identified, Aiken said.

“When we do identify someone, families are grateful,” she said. “People want to know what happened to their loved one, even if it ends in death.”