Eastern State Hospital

The Washington Territorial Legislature commissioned a new mental hospital for the region’s east side in 1886. Western State Hospital, which had opened in 1871 in the old barracks at Fort Steilacoom, was already full and the territory needed another facility on the east side. Medical Lake was chosen because it was near rail lines and by a lake long thought to have medicinal properties.

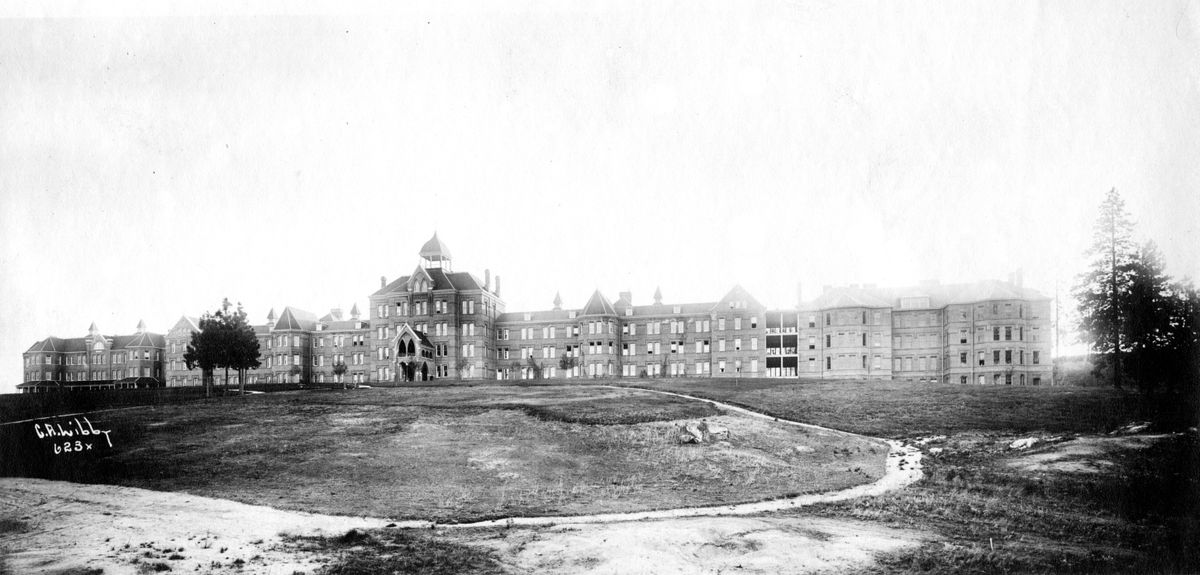

Eastern State Hospital for the Insane opened in 1891. The grand structure was built on a “Kirkbride plan.” Psychiatrist Thomas Kirkbride of Philadelphia advocated asylums with long, meandering wings off a main building so that each section had exposure to sunlight and fresh air. He believed that attractive buildings and grounds were curative for patients.

Though mental hospitals did little more than incarcerate patients, reformers like Dorothea Dix and writer Nellie Bly had exposed the horrors of 19th-century asylums and advocated more humane treatment. The new hospital quickly filled its 800 beds even though it was woefully understaffed and there was little treatment. Many therapies in use then are considered brutal and cruel today. Among them were full-body restraints, injections of insulin to force a psychotic patient into a coma, high-dosage electroconvulsive therapy and frontal lobotomies. Through the first half of the 20th century, forced sterilization was practiced on sex offenders, mentally ill patients and the developmentally handicapped.

Over the years, the state Legislature opened the purse strings periodically to add new buildings to the campus. The main building at ESH today, finished around 1935, was built in front of the original structure. The campus today separates men, women, elderly patients and those who are accused of crimes.

In January 1915, the state began moving developmentally disabled patients to a new facility, the School for the Feeble Minded, just down the road. The name was later changed to Eastern State Custodial School, then Lakeland Village, which continues to care for the severely disabled.

After World War II, the development of better drugs to suppress psychotic symptoms let patients live outside locked facilities. Today, most mental health patients live in the community at large. They try to control their conditions with psychotropic drugs, counseling and monitoring by case workers. ESH, which held more than 2,200 patients in the 1950s, now uses around 300 beds.

A person in a mental health crisis can be admitted to the hospital but usually only stays until the staff believes the patient is stable enough for release.

– Jesse Tinsley