Sam Mellinger: On Pat Summitt, Buddy Ryan, and the parts of their stories the next wave of coaches should be hearing

Pat Summitt, proud owner of one of sports’ all-time steely glares, famously pounded the basketball court so hard that the rings on her hands flattened.

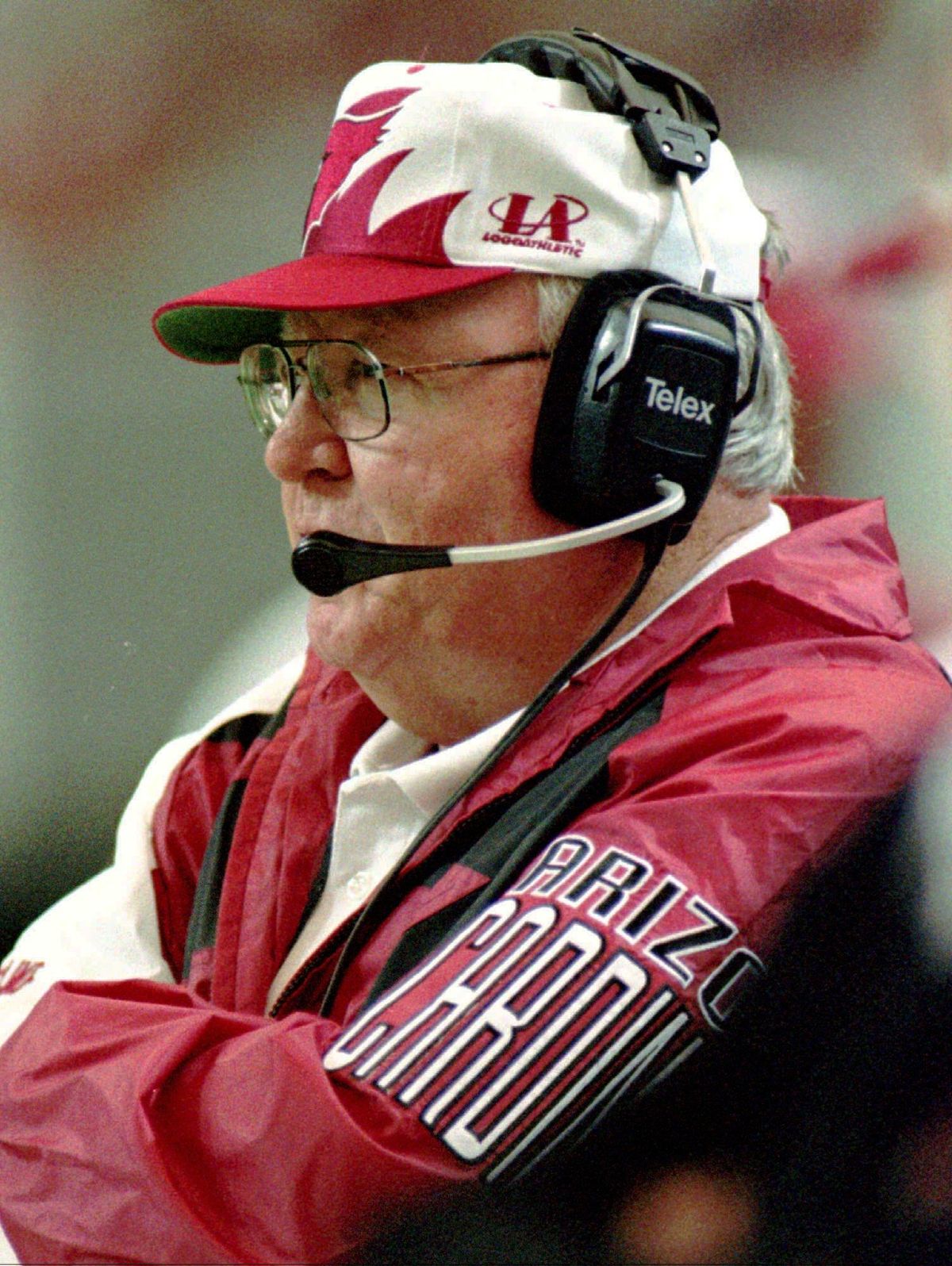

Buddy Ryan, an Army sergeant during the Korean War who was said to punch soldiers in the face to keep them in line, graded his players primarily with one of three adjectives, all of which are insulting, none of which we can print here.

Sports on Tuesday lost two of its most famous hard-ass coaches, Summitt to the heartbreaking effects of Alzheimer’s at age 64, Ryan died at age 82.

All across sports, particularly in the traditionally very different worlds of football and women’s basketball, they are telling reverential stories about two of the greatest and most intense to ever do it.

Summitt was a transcendent figure who won eight national championships and more NCAA Division I basketball games at Tennessee than any coach, men’s or women’s, and had an undeniable role in building and legitimizing women’s sports. Ryan is most famous as the defensive coordinator of the 1985 Chicago Bears, a revolutionary defensive mind who used brute force and demanded the same from his players.

And all across lower levels of sports – from high schools on down, the places where the greatest numbers of our sons and daughters and brothers and sisters compete – these stories are being read by coaches who should be hearing an important message:

Be careful which parts of these stories you try to emulate.

“You can be as tough as you want on your kids,” says Debbie Fay, a Kansas City-area high school volleyball coach since 1983. “But for it to work for you, those kids have to know you love them, and there has to be a payoff.”

The world is always changing, and Fay says she coaches “way, way, waaaay” different now than when she started.

That’s some of why Summitt and Ryan stories should be heard more in awe than as instruction. Sports are famous for copy-catting, but anyone trying to copy Summitt and Ryan would have as much luck trying to surf an active volcano.

Summitt had the guts and ambition and utter lack of damns given to not only create women’s basketball’s first true powerhouse, but to famously scoff at suggestions she take the Tennessee men’s job because “why is that considered a step up?” She helped turn women’s basketball into big business, and then pulled the bear around on a leash. She did it with genius, relentlessness, curse words and compassion.

Who has done what she has, in any sport?

Ryan once did a mocking parody of Hall of Fame coach Joe Gibbs to reporters, announced that he agreed to be the defensive coordinator in Houston to save the head coach’s job, punched the offensive coordinator in the middle of a game, and openly considered anyone who played or coached on the offensive side of the ball not quite slugs but also not quite men.

He is one of the NFL’s all-time great defensive coaches, and he did it with fire, insults, rebellious ideas, and an insatiable swagger.

These are giants in their fields, and they are being remembered appropriately. Dozens of former players paused their lives to fly to Summitt’s nursing home for one last thanks. They retold old stories, rewatched old games, and re-read old letters.

Summitt helped changed the way women’s sports are viewed, making it OK for our sisters and daughters to be coached like our brothers and sons. Her teams helped make athletic strength from women not just acceptable, but admirable.

Ryan’s former players are now grieving a man they were once afraid of, and intimidated by. These are grown men who reached the highest level of a brutal sport, but were often motivated by fear from a chubby grandfather.

He would belittle – he once called one of his linebackers a “big, fat, washroom woman” – and push and demand until the limit, and then belittle and push and demand some more. His blitz-early-and-often way of life was the embodiment of what so many football men are, or feel obligated to pretend to be.

Imitation is the highest form of flattery, or at least that’s the old line, but here imitation would be the surest path to self-destruction.

The line between demanding and loving must be respected. Of those who fail the juggle, some are well-intentioned, some power-starved, and some just destructive jerks.

Even done right, the balance is delicate and constantly changing, and the stakes always high. A smart coach knows they need the support of parents, and the oldest or most-respected kids on the team, and not necessarily in that order.

“How it works for me, you have to tell them, ‘I love you, I care about you,’ ” Fay says. “You have to stroke them a whole lot more than you get in their face. And you can only get in their face once in a while. You can’t do it all the time, because they don’t listen to you anymore.

“Bottom line, they have to know they matter to you in a personal way. As a person, not a product.”

This summer, high school and youth coaches in Kansas City and around the country are being replaced. Some were directly fired, others more passive-aggressively removed. They are surely reading some of the stories about Summitt and Ryan, listening to the most intense parts, and telling themselves they weren’t that hard on the kids.

What they’re missing, though, is the part that drove all those former Tennessee players to fly or all-night drive to Summitt’s death bed, and all those former football players to tears talking about Ryan.

You can be hard on them. That’s not the point. You have to love on them, too, or else nobody is following you anywhere. That’s the genius shared by Summitt and Ryan.

And that’s the part those youth coaches should be emulating.