Washington’s newest national park at Hanford could draw 100,000 visitors by 2018

Hanford High School, abandoned in 1943 when the government took over more than 600 square miles of Eastern Washington for the Manhattan Project, stands as a shell at the town site of Hanford, shown Thursday, Jan. 21, 2016. (Jesse Tinsley / The Spokesman-Review)

HANFORD, Wash. – The sweep of history turned dramatically forward in 1943 on this wind-swept steppe between Rattlesnake Ridge and the Columbia River near Richland. Here, the Manhattan Project took over the landscape and carried mankind across the threshold of the Atomic Age.

In recognition, five project sites at the former Hanford Nuclear Reservation are being developed as part of the new, three-state Manhattan Project National Historical Park. Congress approved creation of the park in 2014 after years of urging from scientists and community leaders.

As a national park, Hanford is expected to become a major tourism draw in Eastern Washington with up to 100,000 visitors a year by 2018 to the former top-secret location.

Hanford is where the U.S. government built the industrial engine for turning uranium into plutonium. The project fueled the development of the atom bomb that exploded over Nagasaki, Japan, on Aug. 9, 1945, effectively ending World War II.

Last November, the National Park Service and the U.S. Department of Energy reached an agreement on how to develop the park. A ceremony at Hanford’s B Reactor - the world’s first full-scale plutonium production reactor - drew several hundred people.

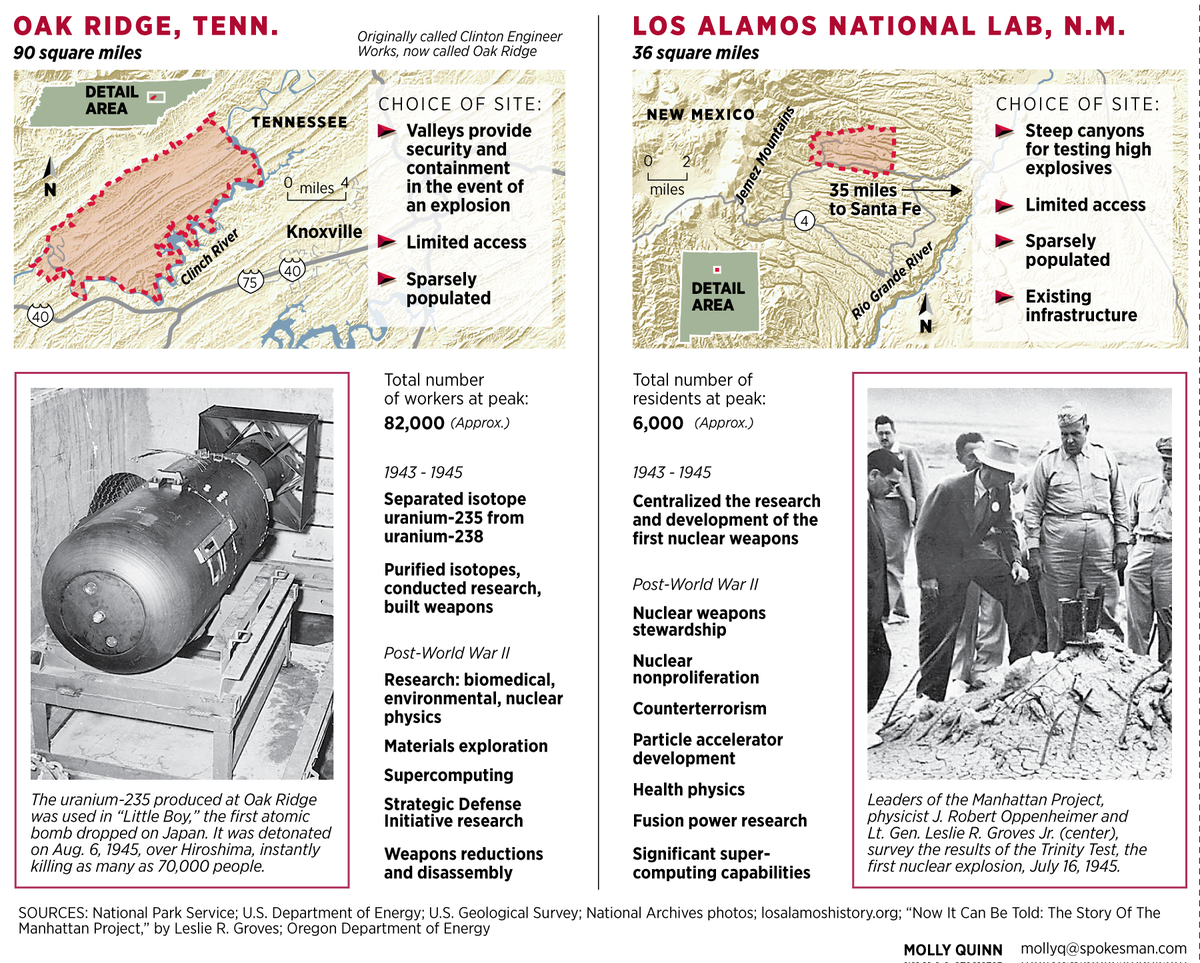

At Hanford, the B Reactor and four pre-Hanford buildings make up the 30-acre park. The other Manhattan Project National Historical Park sites are at Oak Ridge, Tennessee, where uranium was tested, and Los Alamos, New Mexico, where the bombs were designed and developed.

Colleen French, the Department of Energy’s project manager at Hanford, said the site is rich in both cultural and scientific history while its wide-open expanses have become a preserve for animals and plant life.

“It is a pretty fascinating place,” French said.

Residents given 90 days to vacate

Native Americans used the future Hanford site for fishing, hunting and gathering for at least 10,000 years before white settlers came to farm and build communities.

The land drew Wanapum, Yakama, Umatilla, Nez Perce, Walla Walla, Cayuse and Palouse tribal members.

Then the towns of Hanford and White Bluffs grew. When the U.S. government secretly chose the site for plutonium production in 1943, residents were given 90 days to vacate their homes. The towns were demolished with the exception of a bank in White Bluffs and Hanford High School, which was converted to offices for the project.

The 630-square-mile Hanford site offered a lot of land near a major water source - the Columbia River - so that its individual facilities could be separated geographically for security and safety.

The government moved in with 51,000 workers who built what was then Washington’s third-largest city.

A ‘marvel of science’

The heart of the Manhattan Project National Historical Park’s Hanford site is the B Reactor, which used graphite blocks to modulate atomic fission of uranium 238 into plutonium 239.

After a short shutdown following the war, the reactor continued to operate during the Cold War before being shut down and defueled in 1968. It was one of three World War II-era reactors at Hanford.

“You can actually smell the history when you walk into the building,” said Gary Petersen, vice president of the of the Tri-City Development Council. “You can move yourself back in time.”

The 28-by-36-by-36-foot reactor holds 1,200 pounds of graphite that were penetrated by aluminum tubes loaded with uranium. The reaction released neutrons from the uranium to create plutonium, which was later extracted chemically.

Huge pressurized pipes brought water from the Columbia River and forced it through the reactor to absorb the heat given off by the controlled chain reaction.

Control panels show webs of hand-tied wire arrays, switches and gauges.

“It is a marvel of science and engineering capabilities,” said Maynard Plahuta, president of the B Reactor Museum Association, which formed in 1991 and is dedicated to preserving Hanford history.

“When you get there, you get this feeling of, ‘Gosh, How could all of this happen?’ ” Plahuta said.

The American Society of Mechanical Engineers in 1976 published a paper that said “the research work, engineering and planning required to make the reactor operate should be included in history as one of man’s most brilliant scientific and advanced engineering achievements.”

Tiny amounts of plutonium produced in the B Reactor were taken to a remote processing facility eight miles to the south, where the plutonium was extracted and the waste placed in underground tanks, some of which are failing. This is where the focus of the ongoing Hanford cleanup is located today.

The process also caused radioactive iodine to be released into the atmosphere for decades, resulting in a cluster of diseases among people who lived downwind from Hanford. The “downwinders” waged a protracted legal battle, with the final cases being settled in October.

Hanford plutonium was used in the Trinity A-bomb test in New Mexico, and then for the “Fat Boy” bomb that was dropped over Nagasaki.

The reactor is a national historic landmark and is listed on the national historic register.

Most workers during the early years never knew the extent of the atomic effort. Work was compartmentalized at Hanford and the other sites.

“There were only a handful of people who knew what the whole project was,” said French, of the Department of Energy.

Today, groups of visitors from around the world file through the B Reactor during tour season from April to November. About 10,000 visitors toured the park last year. Regular tours started in 2009.

Registration for this tour season has not started; sign-ups will be available at manhattanprojectbreactor.hanford.gov.

A park museum at 2000 Logston Blvd. is located along state Highway 240 just northwest of Jadwin Avenue. It is open to the public Mondays through Thursdays from 8 a.m. to 4 p.m. and on Saturdays during tour season.

Remants of former settlements part of the park

Most of the original settlements at Hanford and White Bluffs were erased from the landscape. Stumps from an old orchard stand along the main road, almost like tombstones of the past. Old sidewalks and streets are still there.

The Bruggemann farm near the B Reactor is one of four pre-Hanford sites in the park.

The farm’s old warehouse, built out of round native rock, still stands. The farmhouse was torn down, apparently left in a heap of stones next to the warehouse.

Clay irrigation pipes and other remnants are visible on the ground.

The other pre-Hanford sites are the shell of a small 1907 bank of the town of White Bluffs, the exterior walls of the old Hanford High School and an irrigation pumphouse that served the farms in what was once known as the Priest Rapids Valley.

The park is undertaking preservation, restoration and planning for those sites.

Visitors could reach 100,000 annually by 2018

Regional support for the national historical park has been strong.

In a copy of his testimony before Congress, Petersen, of the economic development agency, said that a big part of the story is the thousands of men and women who worked on a project “that became a turning point in the history of the United States and the world.”

The Tri-Cities Visitor and Convention Bureau estimates the value of heritage tourism to the park at $1.5 to $2 million a year based on 10,000 annual visitors.

In an interview, Petersen said the National Park Service estimates the number of visitors to Hanford will increase to about 100,000 a year by 2018.

He said creation of the park is still relatively unknown even around the Tri-Cities. “It’s a big deal. I don’t think the community or the state have realized it yet,” he said.

Tracy Atkins, the National Park Service’s project manager, said the agency is developing a document that will define the purpose of the park, its national significance, interpretive themes and resources needing protection.

The goal is to increase accessibility and the interpretive value of Hanford history.

The park story will extend beyond its boundaries to consider the broad impact of atomic energy, including its benefits in areas such as health care and risks such as nuclear war.

The National Park Service has taken on other controversial sites in its mission, such as Japanese internment camps from World War II and the Andersonville prisoner camp from the Civil War.

During a meeting in Richland Thursday, agency officials will want to hear ideas from the public.

“What are the important stories we should tell?” Atkins said. “Down the road, what experiences would people like to see in the park?”

Plahuta said the B Reactor Museum Association is arguing for open access to the reactor and the neighboring Bruggemann farm.

Visitor facilities will likely be needed in the vicinity of the B Reactor, which is on the far northwest side of the Hanford Site, Petersen said.

Last fall, the park service convened a scholar’s forum to help in planning. Among those attending was Yasuyoshi Komizo, the chairman of the Hiroshima Peace Culture Foundation.

The forum suggested that controversial topics not be avoided and could include nuclear proliferation, arms control, secrecy and spies, the ethics of dropping atomic bombs, segregation in the work camps and civilian terror.

In November, the park service director received a letter from the mayors of Nagasaki and Hiroshima, the two cities hit by atomic bonds in 1945. The letter calls for a factual approach to interpreting the Manhattan Project, with the mayors writing, “it is necessary to fully describe what happened to the people under the mushroom clouds.”

“In other words,” they wrote, “exhibitions must reveal the inhumanity of nuclear weapons by clearly showing that the atomic bombs were dropped mainly on innocent civilians such as women, children and the elderly…”

Atkins, the NPS park manager, said the park interpretation will be factual and will include the Japanese point of view without advocacy of one view over another.

The idea, Atkins said, is to “pose questions that encourage further reflection.”