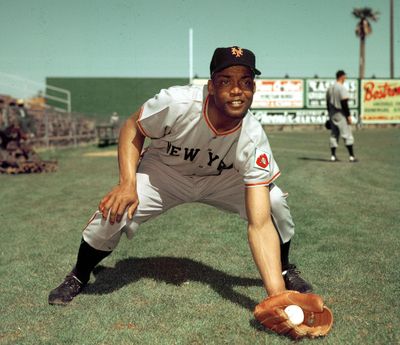

Hall of Fame baseball player Monte Irvin dies at 96

HOUSTON – Hall of Famer Monte Irvin, a power-hitting outfielder who starred for the New York Giants in the 1950s in a career abbreviated by major league baseball’s exclusion of black players, has died. He was 96.

The Hall of Fame said Irvin died Monday night of natural causes at his Houston home.

Irvin was 30 when he joined the Giants in 1949, two years after Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier. Irvin spent seven of his eight big league seasons with the Giants and one year with the Chicago Cubs in 1956. A native of Haleburg, Alabama, Irvin played in the Negro, Mexican and Puerto Rican leagues during his 20s.

Irvin batted .300 or more three times with a high of .329 in 1953. He finished with a career average of .293 with 99 homers and 443 RBIs, numbers that would have surely been far higher if not for the game’s racial segregation.

“Today is a sad, sad day for me,” said Hall of Famer Willie Mays, a teammate of Irvin’s with the Giants. “I lost someone I cared about and admired very, very much; someone who was like a second father to me. Monte was a kind of guy that you had to be around to get to know. But once you became friends, he always had your back. You had a friend for life.

“Monte Irvin was a great left fielder. Monte Irvin was a great man. I will miss him. There are no words for how I feel today. I could say so much more about Monte, but this is not so easy to do right now.”

Irvin was one of the most important contributors during the Giants’ amazing pennant drive in 1951 when they overtook the Brooklyn Dodgers after trailing by 13 1/2 games in mid-August. Irvin batted .312 with 24 homers and an N.L.-leading 121 RBIs.

That year Irvin teamed with Hank Thompson and Mays to form the first all-black outfield in the majors. He finished third in the N.L.’s MVP voting.

Irvin was rewarded with a contract estimated at $25,000, a pay raise of almost 100 percent.

Unfortunately for Irvin he could not repeat his 1951 season in `52.

On April 2 in an exhibition game against the Cleveland Indians in Denver, he suffered a compound fracture and dislocation of the right ankle after a hard slide into third base. Four months later, Irvin was back in action. In 1954 he helped the Giants sweep Cleveland to win the World Series.

Irvin’s days in a Giants uniform came to end on June 24, 1955, at the age of 36, when his contract was sold to Minneapolis of the minor leagues. He played one final year in the majors with the Cubs before retiring in May 1957 while with Los Angeles of the Pacific Coast League.

Commissioner Rob Manfred called Irvin a leader during a transformational era for baseball.

“Monte loved our game dearly, bridged eras of its history and touched many lives,” Manfred said. “Major League Baseball will forever be grateful to courageous individuals like Monte Irvin.”

After his retirement from baseball, Irvin worked as a scout for the New York Mets and on the public relations staff of a brewery.

On Aug. 21, 1968, Irvin made history when baseball commissioner William D. Eckert named him assistant director of public relations for baseball, becoming the first black chosen to an executive position in professional baseball’s hierarchy. Later, Irvin was named special assistant to commissioner Bowie Kuhn.

In 1973, Irvin was elected to the Hall of Fame by the Negro League Committee. On Aug. 6, 1973, Irvin entered the Hall along with pitcher Warren Spahn and outfielder Roberto Clemente, who months earlier died in a plane crash.

“My only wish is that major league fans could have seen me when I was at my best … in the Negro Leagues,” Irvin said. “I sincerely believe I could have set some batting records comparable to DiMaggio, Mays, Aaron, Williams – 600 or 700 home runs, that type of thing.”

During his tenure in the commissioner’s office, Irvin attended many baseball gatherings and was often seen at the ballparks around the major and minor leagues.

Despite retiring before the Giants moved to San Francisco, Irvin kept ties with the organization. He had his number retired in 2010, was one of several Hall of Famers to throw out a ceremonial first pitch later that season at the World Series and went to the White House last summer when San Francisco’s 2014 World Series championship team was honored.

“Monte was a true gentleman whose exceptional baseball talent was only surpassed by his character and kindness,” Giants CEO Larry Baer said. “He was a great ambassador for the game throughout his playing career and beyond. As the first Giant and one of the first African-American players to help integrate Major League Baseball, he served as a role model and mentor to so many who followed in his footsteps – including Willie Mays.”

Irvin is survived by daughters Patricia Irvin Gordon and Pamela Irvin Fields and two granddaughters.