KSPS documentary highlights Maxey’s accomplishments

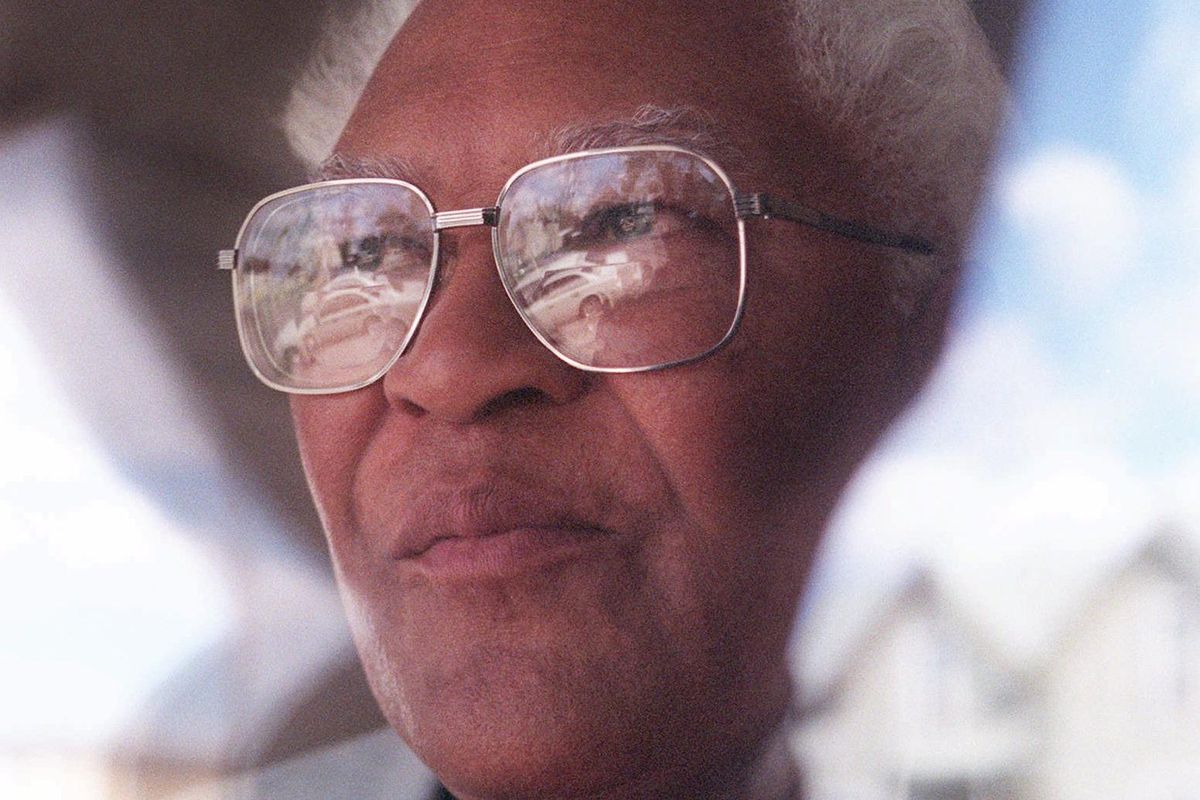

Carl Maxey’s story contains enough material to fill several biographies.

It’s impossible to condense his life down to just one accomplishment. He was a medic in the military, a champion boxer, a civil rights pioneer and an advocate for the underprivileged and disenfranchised. He was also Spokane’s first practicing black attorney, he ran for Senate and was nominated for the Supreme Court, and he fought racism and discrimination in Spokane when nobody else was.

Maxey is now the subject of an new documentary, “Carl Maxey: A Fighting Life,” produced by Spokane’s public television station KSPS and premiering Thursday. The film, based on a 2008 biography by retired Spokesman-Review staff writer Jim Kershner, was directed by Jim Zimmer and written and edited by Mary DeCesare. It covers Maxey’s momentous career in a brisk, information-packed hour.

“We’re always looking for people who are making a difference in our community,” DeCesare said. “Carl’s story is very timely. The things that he was facing in his life, you can see the same patterns happening even today. It’s an important issue, and I think it’s very important in a community that isn’t as diverse as other places.”

Zimmer and DeCesare, who work as producers at KSPS, have previously produced the documentaries “Born to Learn: Brain Science and Early Learning” and “Uncharted Territory,” a film about the explorer David Thompson. Part of the challenge of compiling this film was covering all the bases while keeping it a manageable length.

“There’s so much that we couldn’t talk about,” DeCesare said. “We just didn’t have time, or the story was too hard to develop.”

“It’s hard to imagine that an hour isn’t enough to tell a person’s life,” Zimmer said.

But “A Fighting Life” hits all of the important signposts in Maxey’s remarkable life, from his birth in Tacoma in 1924 to his suicide in 1997.

By the age of 2, Maxey was orphaned and landed in the Spokane Children’s Home. Maxey was the only black child in the home, and after 10 years, he was unceremoniously ousted along with a Native American boy named Milton Burns. The meeting that decided Maxey’s ejection was recorded in secretarial minutes; Maxey would later frame the notes and hang them in his law offices.

Maxey and Burns were transferred to the Sacred Heart Indian Mission in DeSmet, Idaho, where Maxey, under the tutelage of the Rev. Cornelius Byrne, first developed an affinity for boxing. He returned to Spokane as a teenager, at a time when only 700 of Spokane’s 100,000 residents were African-American.

He worked as a waiter at the all-white Spokane City Club, and eventually graduated from Gonzaga Prep. After serving in the Army, Maxey attended the University of Oregon on a track scholarship, later transferring to Gonzaga Law School, where he also competed as an undefeated boxer. In 1951, Maxey became the first black student in Eastern Washington to pass the bar exam, and yet he was still treated like a second-class citizen.

“There was a real divide between people who thought Carl Maxey was a hero and those who thought he was just a troublemaker who was threatening the status quo,” Kershner says in the film.

As a lawyer, Maxey set his sights on cases involving racism and segregation. He represented the owners of a black nightclub that was refused a liquor license and a black teacher who was denied a job with the school district, and he targeted establishments refusing service to customers of color.

“It really incenses you that this stuff existed here, and it makes you realize what a champion Carl had to become,” Zimmer said. “He was a bull in a china shop when it came to challenging these things.”

“He couldn’t handle seeing injustice,” DeCesare said, “and it makes you look at yourself and say, ‘What can I do to stop the injustices of today?’ ”

Despite his beneficial social work, Maxey was also an incendiary local figure. He was vehemently opposed to the Vietnam War, going on to defend the protestors arrested for inciting a riot outside Seattle’s Federal Courthouse in 1970.

Perhaps most controversial was Maxey’s work for the Coe family, first during the sentencing phase of Kevin Coe’s rape trial, and later his defense of Ruth Coe, who was convicted of attempting to take out a hit on the judge and prosecutor who convicted her son. Donald Brockett, the prosecuting attorney who Ruth Coe wanted made a “vegetable” the rest of his life, is interviewed in the film, saying that he felt “betrayed” when Maxey took on the case.

Production on “Carl Maxey: A Fighting Life” took a year to complete, and Zimmer and DeCesare conducted about two dozen interviews with local politicians, journalists and lawyers, as well as Maxey’s wife and sons.

“Doing a documentary about someone that people still remember had its own challenges, because we’d never done that before,” DeCesare said. “That’s why we interviewed as many people as we did: We wanted to be sure we were telling the right story.”

“You cast a net as wide and far as you can, because you’re trying to gather so many different things,” Zimmer said. “You don’t want to leave any rock unturned, in terms of who has a photo or where a clipping might be. … We were lucky because we were able to start with the work Jim Kershner had done already. … He was very generous in sharing the information he had and the people he knew.”

Concurrently with its television premiere, “Carl Maxey: A Fighting Life” with screen during a reception at the Bing Crosby Theater on Thursday. The filmmakers say the program will eventually be uploaded online and will be re-broadcast several times on KSPS.

“I think it’s important that this is seen locally by a wide range of ages,” Zimmer said. “There are generations of people who should look at Carl’s life and see what one man can accomplish, and to have a perspective on what Spokane was and what it could have still been had he not been here.”