Carl Maxey: ‘From black scratch’

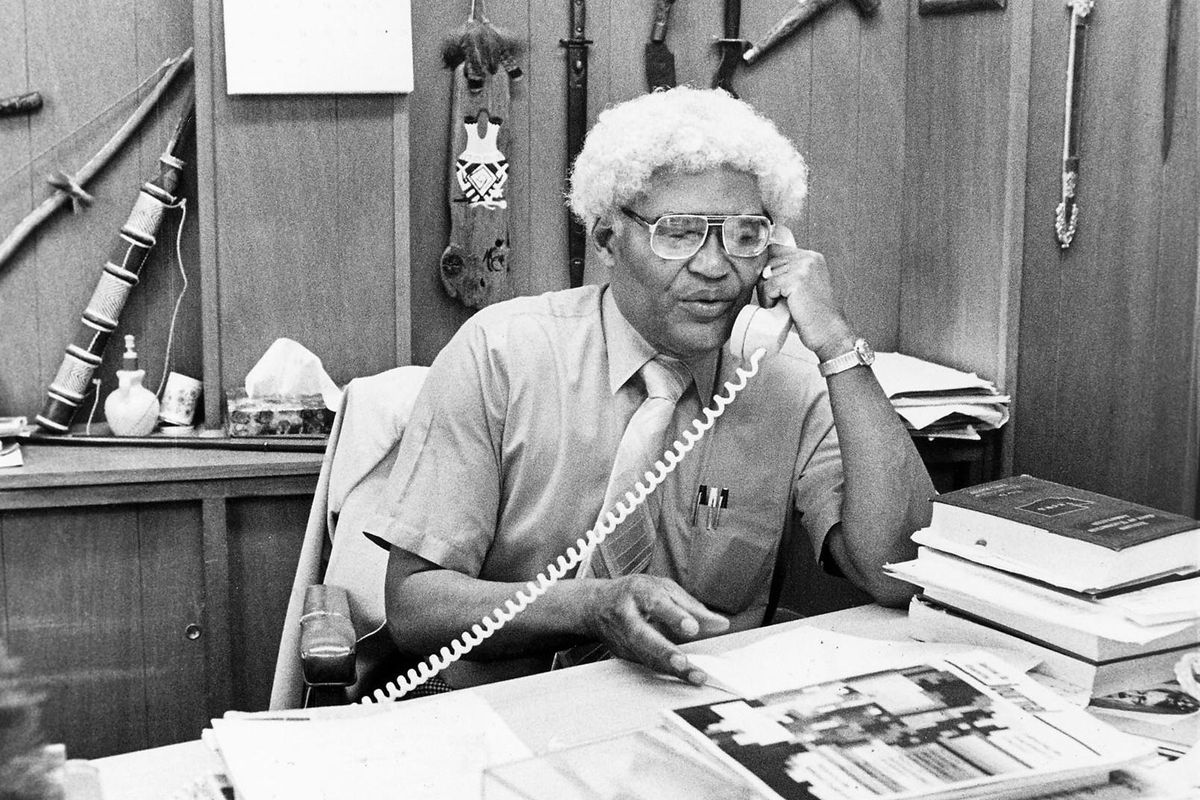

Spokane Lawyer Carl Maxey is shown at his home with his two sons, Beven, 18, at left, a star athlete at Lewis and Clark High School, and Bill, 25, a University of Oregon Law School student. Maxey and his wife Merrie Lou were married in the summer of 1974. It is his second marriage. Photographed March 1975. (File photo, The Spokane Daily Chronicle)

Look for a rags-to-riches story in Spokane, and amid all the lions of business and industry, few tales equal that of an illegitimate black orphan who struggled through a resistant, white society to become one of the city’s most prominent and controversial lawyers.

Forty years ago, Carl Maxey was a waiter at the Spokane Club. He remembers serving whiskey to the city’s white leaders as they snapped their fingers and called, “Here, boy.”

Sunday (March 29, 1981), hundreds of prominent judges, lawyers, old friends and clients from around the country will gather at a Ridpath Motor Inn gala honoring the 56-year-old man’s 30 years in the practice of law.

In the limelight will be the same person who years ago listened in the shadows with other black waiters, fascinated as Spokane’s powerful, white lawyers discussed their deeds in court.

At the city club, which Maxey also remembers as one of the principal employers of Spokane blacks in the ’30s, and later in the segregated Army of World War II, was born the social consciousness that ultimately led Maxey into prominence as a civil rights lawyer, a champion of the underdog and a dissenter.

“I have a love affair with the city of Spokane. But it’s bittersweet,” Maxey said in an interview.

“I could feel affection for the guys at the club. Yet I know what they thought about me. I fight ’em all the time, but I don’t hate ’em. As the guy said, some of my best friends are white.”

He was characteristically blunt when asked how he thinks blacks are treated in Spokane now. “It’s like a guy who gets to know a dog. The longer you know him, the friendlier you are to him, but he’s always a dog.”

Spokane is a “totally insensitive town” to racial problems, he said. “I doubt the people who make policy in Spokane ever associate with black people. Jim Chase (city councilman and a candidate for mayor) is obviously an exception. I don’t know if he’s appreciated fully as a man as much as a symbol, and he’s an immense man.”

Maxey, who never has joined the Spokane Club even though he’s now part of the legal establishment, said black professionals still are few and far between in Eastern Washington.

“You just ask the club people to look around and count noses, and see how many blacks are members.”

Maxey’s extraordinary struggle to the top began at the very bottom.

“I was born an illegitimate kid and I was adopted by Carl and Carolyn Maxey. That’s where I got my name. They both died. I don’t have much memory of them.”

From age 2 to 11 he lived in the Spokane Children’s Home. “I remember my mother coming to visit me in the orphanage and I remember being taken from the orphanage to the funeral. Beyond that, I don’t remember …”

The orphanage later was closed and, because there was nowhere else to stay, Maxey was placed in the county’s juvenile detention center, even though he had committed no crime. He was let out to attend school during the day.

A few months later, Maxey was placed at the Sacred Heart Indian Mission operated by Jesuits in DeSmet, Idaho. Looking at a worn picture of boys with whom he lived at the mission, Maxey mused, “Just about all the kids in that picture are dead. From alcohol abuse, drugs …”

At the mission, Maxey said, he grew “under the care and guidance of a wonderful man, Father Cornelius Byrne.

“I haven’t known any fathers in my life, and I suppose the closest thing I had to one was that Jesuit priest; and Joey August, my boxing coach; and a guy from the Spokane city club, Ross Houston, who used to be head waiter,” Maxey said.

He returned to Spokane to attend Gonzaga Prep, where he lettered in football, basketball and track. After school, he went to the Spokane Club, where he worked his way up from busboy to waiter and finally bartender.

“I have a lot of good memories of the city club, contrary to what a lot of people would think. The memories of the people I worked with are reflective of the old black community in Spokane, people of integrity.

“Even though we were humiliated in pay – 25 cents an hour and all the food we could steal – and the snapping of the finger, the command, ‘boy,’ I also had a lot of respect for the members. I got along good with ’em. I listened well. The white man taught me many things,” Maxey said.

He remembers the men, particularly the lawyers, who led Spokane in those days. He even remembers what they drank: “J.P. Graves. He drank old-fashioneds.”

“Mr. Post, Mr. Danskin, Mr. Randall, Lester Edge Sr., all those famous old guys. The stories they told were fascinating. You could see they were the sources of power, that they had an effect on lives. I don’t mean to suggest they pulled me aside. You didn’t do that at the city club in those days.

“It was enough to see them in control of your life; you wanted to get an equal footing,” Maxey said.

When war broke out, he entered the Army and served as a medic. At the Spokane Club and in the Army, which was “outrageously” segregated, “my social awareness was born,” Maxey said.

After release from the service in 1946, he attended the University of Oregon, then Gonzaga University Law School. In college, he was a prominent athlete.

Maxey was undefeated in intercollegiate boxing. He attempted to make the 1948 Olympic team, but lost his first bout in the trials. In 1950, he won the NCAA light heavyweight boxing championship by defeating the captain of that 1948 Olympic team.

In college, Maxey said, he considered becoming a dentist “but I lost all interest in teeth, and I had a feeling the law business embraced the freedom my spirit needs.”

After graduation from Gonzaga Law School in 1951, in a remarkable class whose members went on to become some of the state’s most prominent lawyers and judges, Maxey borrowed $150 from his boxing coach and opened an office with fellow attorney Vic Felice.

After 10 years, he joined Leo Fredrickson and Robert Bell, forming the law firm with which he still remains. His law partners are sponsoring Sunday’s celebration.

Those first few years of law practice, Maxey remembers, were lean. “I was starving. It was terrible. We’d go down and beg the judges to let us represent an indigent in a criminal case,” for which the county paid $10 a day. “Some months I’d make $45.”

“My road,” Maxey said, “was a little tougher than the rest of ’em because I had to educate a community to come to a black professional person.” But, “when I turned the corner I turned it running. Hard work is really a virtue. I got a strong work ethic.”

He began to acquire a reputation – and a good deal of vilification – representing people accused of being communists during the McCarthy era.

In the early 60s, after representing a series of notorious murderers, rapists, child molesters, baby killers and abortionists – “all the cases nobody else wanted” – Maxey began a series of major civil rights cases.

He won a ruling preventing the closure of stores on Sunday. In another case, he persuaded a court to rule that release from school for religious education purposes was an infringement on separation of church and state.

Representing a black named Eugene Breckenridge, Maxey sued Spokane School District 81 and an out-of-court settlement compelled the district to hire its first black school teacher. Breckenridge later became head of the Washington Education Association.

As hair length became an issue, Maxey represented a boy who won court permission to wear long hair at University High School, which “kind of opened the door to hair in Spokane,” Maxey said.

In another case, he said with a chuckle, he represented a black official from an African embassy who was refused a haircut by a Spokane barber. Maxey won the case, but the barber quit rather than give the court-ordered haircut.

As society was torn by the Vietnam War, Maxey represented hundreds of young men who resisted the draft.

Once, when Vice President Spiro T. Agnew was in Spokane, the student body president of Gonzaga called Agnew a “warmonger,” and was arrested for disorderly conduct. Maxey got the conviction reversed on appeal.

He met a future law partner, Pat Stiley, when Stiley was arrested during a demonstration for carrying a protest sign up the stairs at City Hall. Maxey represented him on a charge of disorderly conduct and won the case.

In another precedent-setting case, Maxey won a ruling that it was improper for the Spokane City Council to debate its business in secret and conduct only the voting in public.

He took city fathers to court when they wanted to deny permission to show the first Muhammad Ali - Joe Frazier boxing match on television in the Coliseum. “A lot of ’em felt he (Ali) was a draft dodger,” Maxey recalls. In an out-of-court settlement the city agreed to allow the event.

Maxey entered the political arena in 1970, running against U.S. Sen. Henry Jackson in the Democratic primary. The state Democratic convention endorsed Maxey, but as Maxey tells it, numerous Republicans crossed over in the primary to vote for Jackson, “who is a Republican anyway.”

That same year, Maxey represented the “Seattle 7,” a group of students from eastern colleges who formed the Seattle Liberation Front at the height of Vietnam dissent, and were tried in Tacoma for conspiracy to destroy public property and to advocate violence.

After a violent demonstration in the courthouse, a mistrial was declared and the case ended with the seven pleading guilty to contempt of court charges.

Another protest case involved several Washington State University students who were accused of firing shotguns at a fraternity house during student unrest. “It was all about racism, but it seems to me it all got started over an intramural basketball game,” Maxey said with a chuckle.

Students conducted vigils outside the Colfax jail where Maxey’s clients were held, and one day 43 of the demonstrators were arrested, and Maxey represented them, too. “A great many of ‘em went on to become celebrated educators,” Maxey said.

More recently, he represented Long Lake property owners in a precedent-setting lawsuit against the city of Spokane and the state Ecology Department over discharge of untreated sewage into the Spokane River. Maxey’s clients won a $368,596 judgment.

Amid all the controversial cases, he and his partners have specialized in divorce cases. Maxey explained his interest in that area: “It’s the toughest area of practice of all of ’em.

“There’s nothing that brings out hostility more than any run of the mill divorce. I’ve had death threats night after night in divorce cases. People have been killed in my office over a divorce case.

“It’s a war; it’s not a game. It’s something that isn’t done too well (by lawyers) and it needs the most sensitivity. When you’ve won that kid for a man or a woman who ought to have custody, you’ve taken something ordinary and made a real adventure out of it,” Maxey said.

“You know what I’m most proud of? I’ve never sent out a bill, except in rare instances where the fee has been contested. And we’ve had a rule down here that we have to give away 20 percent of our time to public service. That’s free law, to people who can’t afford it but need help right away.”

What has he felt when people vilified him for his political and social activism? “I got a great sense of humor. I think if the town looks back at it, and takes a guy starting from scratch, black scratch, let’s try to match the good things I’ve done,” Maxey said.

Will he practice law the rest of his life? “You are what you are,” Maxey said. “I will practice for the forseeable future.” He hopes to reduce his workload, select only the most interesting cases, and will appreciate the assistance of his son, attorney Bill Maxey, and son Bevan Maxey, now a first-year student at Gonzaga Law School.

Among his many legal battles, Maxey’s assignments to advisory committees on racism, his 1976 candidacy as Eugene McCarthy’s presidential running mate on the Washington Independent Party ticket, and countless other tasks, what does Maxey view as his most worthwhile accomplishment?

With a bellow of laughter, he said, “living through all this bull——.”