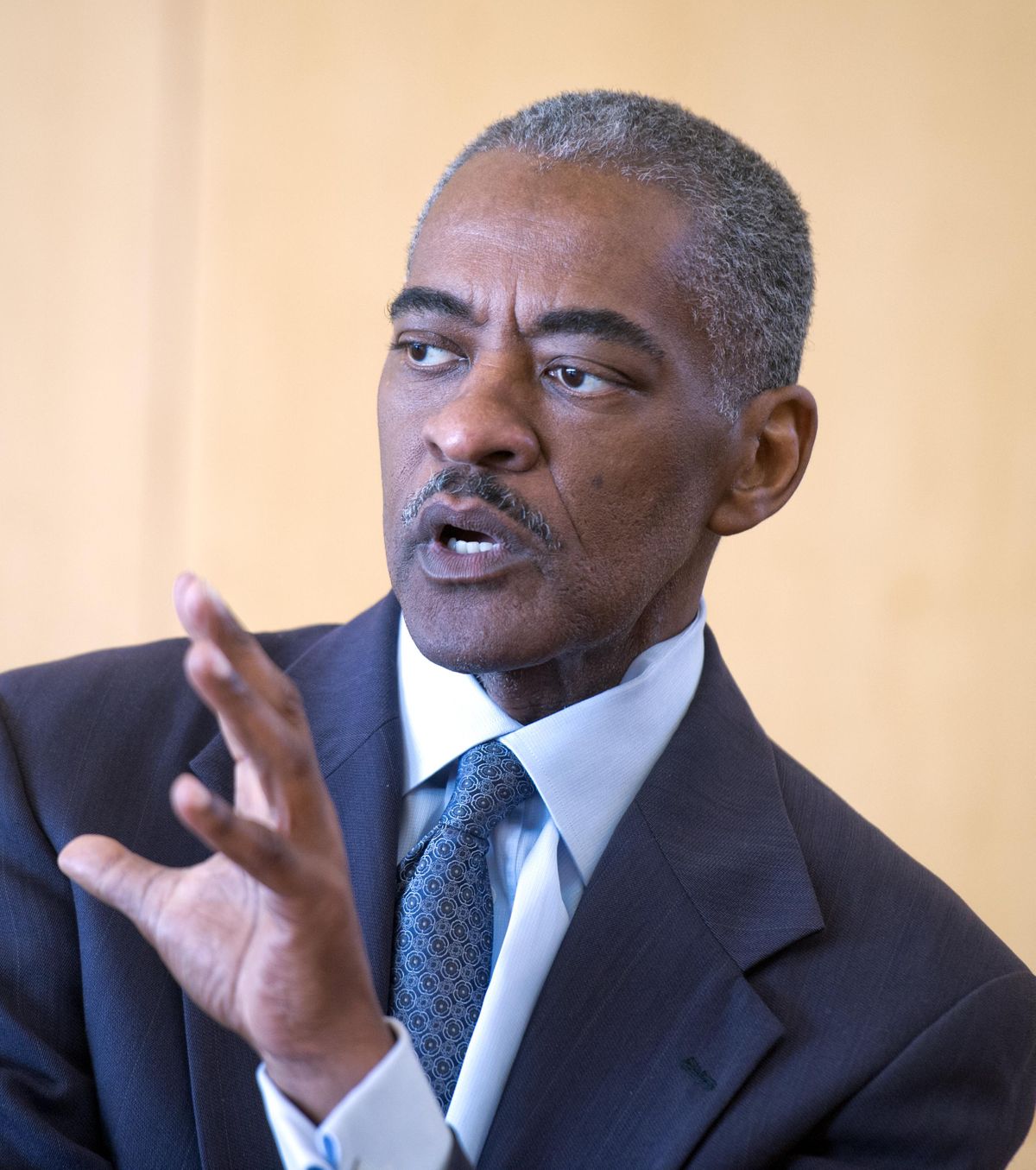

Elson Floyd’s drive helped bring a medical school to Spokane

Spokane civic leaders had been working for years to expand medical education in the region by the time Elson Floyd was named president of Washington State University.

The strategy at the time was to get the University of Washington to send more students, for more years, to the East Side of the state through an existing regional medical school program.

But when that UW-driven plan hit various speed bumps, Floyd “was the guy who said ‘OK, I see something out of this’ ” and moved forward on a different path: a new medical school at WSU, said Todd Mielke, chief executive officer of Greater Spokane Inc.

The Elson S. Floyd College of Medicine won preliminary accreditation this year and will enroll its first class of medical students in August. Floyd didn’t live to see that milestone, however; he died of complications from cancer in 2015.

Don Barbieri, a WSU regent, said he and Floyd often talked about Barbieri’s favorite saying, “the Lord hates a coward.” When it came to WSU taking the big step of pursuing its own medical school, “Elson said, ‘We’re going to do this,’ ” Barbieri recently recalled.

That decisiveness was one of Floyd’s most notable characteristics, said WSU-Spokane Chancellor Lisa Brown, who was appointed by Floyd and who worked with him to transform the medical school dream to reality.

“Higher ed can be a place where there’s a lot of deliberation and process; things don’t move very quickly,” Brown said. But “refreshingly,” she said, once a decision was made, Floyd made it happen.

Floyd himself coined the term “Elson time.”

Said Barbieri, “He would get up early and text, ‘Don, are you up?’ ”

Elson time accelerated as Floyd battled colon cancer.

“He was very private about his illness, but there was a sense of urgency,” Brown said.

Legislators in Olympia noted his weight loss as Floyd traveled between Pullman and the state Capitol early in 2015 to lobby for the new law that would allow WSU to open a medical school and for the seed money to get it started.

But Floyd said nothing publicly until he asked WSU regents for time off to tend to his health on June 5, 2015. He died on June 20.

Both Barbieri and Brown say Floyd viewed medical education as part of WSU’s mission as a land-grant university – to teach practical skills for the benefit of all state residents.

“He was really fueled by the mission that we would make a difference by recruiting these students from small communities and returning them to these communities as physicians,” Brown said.

Besides providing more doctors for the region, the medical school is seen as a way to bring more vibrancy to Spokane’s University District and an economic development engine that will attract staff, students, research dollars and commercial spinoffs, said GSI’s Mielke.

Barbieri believes future generations will look at the founding of a medical school in Spokane as “one of the biggest history-making events” in the region.

And while he thinks the need for the medical school would have made it happen even without Floyd, Barbieri said the late president’s “personality, his presence, his relentlessness and sincerity was a changer” when it came to making the case for the school now.

Brown said Floyd was an imposing figure whose gravitas was apparent when he entered a room. “I think he carried with himself the sense of what it meant for him as a black man in America to have accomplished the things he accomplished,” she said.

Nevertheless, he had a fine sense of humor and was popular with students. Obituary after obituary referred to him as “beloved.”

Said Barbieri, “I miss him dearly. He was a wonderful, wonderful man.”