This column reflects the opinion of the writer. Learn about the differences between a news story and an opinion column.

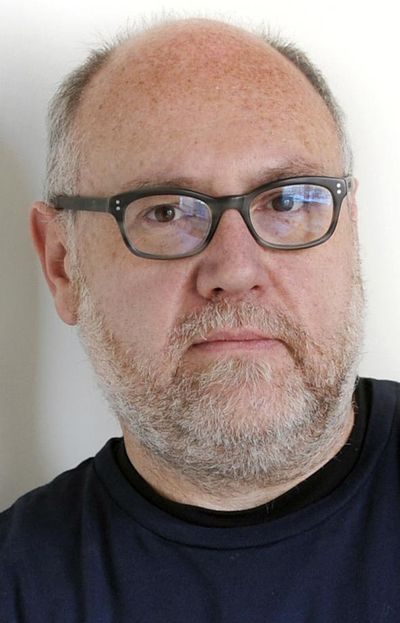

Shawn Vestal: Cappel report’s biggest revelation is how much still hasn’t been revealed

Or does it vanish into a black hole called the city attorney’s office?

Those are the chief questions left by the lengthy and discouraging Cappel report, which concluded that administration officials, in order to protect the mayor’s re-election bid, purposefully delayed the release of public records that exposed a carefully crafted fib.

Condon denies it, saying “there was absolutely no intentional effort to keep documents from the public.” His chief spokesman, Brian Coddington, said that there were delays with the release of the records, but that there was no motivation to hide documents. City administrator Theresa Sanders said, “Not only was there not intent, there wasn’t even a discussion about it.”

So … is anyone to blame? Was it all a giant accident? Because it’s clear that City Hall had potentially embarrassing records it was legally required to make public, and that it withheld them until after the election. Is it mere coincidence that the withheld records were exactly the records one would withhold if one were withholding records to affect the election?

Ultimately, the people who withheld them – city attorneys Nancy Isserlis and Pat Dalton, among others – won’t say why. To hear Condon and other City Hall officials tell it, the responsibility for the morass falls primarily on … the investigator. On politics. On destructive journalists. On imprecise policies.

I do think the investigator, former prosecutor Kris Cappel of Seattle’s Seabold Group, drew inferences from an incomplete picture – reasonable inferences, but still. I do think that the battle between the press and the administration has sometimes tightened into an insoluble knot, as has the conflict between the mayor and the City Council. And I don’t believe it’s fair to demand mea culpas from people who don’t believe they did anything wrong.

But it is very difficult to understand the degree to which this administration seems to believe that it did nothing wrong.

Sanders and Coddington agreed to talk about the report, arguing they did what they did to protect a city employee, and that their role in the public records process was hands-off and above-board. They also expressed concerns about the onerous public-records process at City Hall, and the need to improve the way the city responds.

“Reflecting back on the decisions that I made and the action I took, I feel good about the decisions,” Sanders said. “As I look at it now in the light of six months later, in review, clearly I think we need a better process for handling employee complaints. … I think you’ll see, rather quickly, some significant changes in our processes and our practices.”

Coddington said, “I don’t want any of this to sound like we’re making excuses or trying to justify. We’ve been asked to explain and we’re trying to do that. The bottom line is, we need to figure out how to better handle these kind of difficult and complex situations so the next time this happens, we’re better for having gone through the experience. If we can’t learn from this, then that’s the failure. ”

The Cappel report examined the way the city handled the disintegration of the Straub regime, the shifting of police spokeswoman Monique Cotton into a new job and the misleading story told to the public about that, and the process by which the city responded to public records requests about it.

The biggest impression left is that many questions remain unanswered, primarily because of vigorous and ongoing efforts to keep them that way. Among them:

Did City Hall purposefully create a black box of the city attorney’s office in which to hide secrets? Page after page, the Cappel report notes that some piece of information is unknown because it’s in that black box – unreleased because of attorney-client privilege or unknown because none of the several city attorneys working on the case agreed to be interviewed by Cappel.

These attorneys work for Condon – though an idealistic fool might argue they should be working for citizens – and Condon could have chosen to waive attorney-client privilege or taken a less secretive approach. He repeatedly did not. His rationale: It was necessary to keep potentially damaging information secret because of possible lawsuits.

It is clear that secret-keeping was a systemic priority. Typically, the city clerk handles requests and oversees the release of records, though legal review isn’t uncommon. In this case – following requests from The Spokesman-Review and several others – the city attorney’s office took over to an unusual degree, Cappel concluded, making the decisions about what to release and when.

What reason did the city attorney give for taking over the process? When the office informed the city clerk that it would be reviewing the documents, it gave “pending litigation” as the reason. Eventually, pending litigation was a very real prospect. But the report said, “There was no ‘pending litigation’ involving Chief Straub or Ms. Cotton at the time of this directive.” The investigation concluded that Isserlis was closely monitoring the process and kept Sanders in the loop.

Why did the city attorney’s office fail to release Sanders’ notes from meetings with Cotton? We don’t know. Coddington points to a sharp increase in records requests, and the work involved in responding to them, as a possible explanation for how something may have gone wrong. But these notes were high-profile records in a singular case; I find it especially unpersuasive to argue that they were simply routine papers in a pile, rather than records to which people were paying a great deal of careful attention.

The handwritten notes included the fact that Cotton said Straub had sexually harassed her, but that she didn’t want to pursue an investigation of those charges (but was willing to pursue one involving Straub’s vulgar, abusive leadership). Sanders forwarded these notes to Isserlis in the spring of 2015; Isserlis did not notify the city clerk that she had the records until Nov. 10, 2015, a week after the election. Cappel concluded that the two had intentionally withheld the records until after the election. She also said that Condon and Coddington were closely involved in discussions about the release of records, but she backed away from an initial conclusion that they had intentionally withheld the records.

Sanders denies the allegation against her unequivocally. Her attorney has blasted the report, calling its conclusion “defamatory.”

“I turned the records over to the city attorney in the spring after I felt the employee issue had been resolved,” Sanders said. “From there it was my expectation that the records were in the hands of the public records experts.”

Isserlis says … nothing.

Why did a city attorney delay the public release of Straub’s text to Cotton saying “Love you. You are an awesome partner and best friend”? This August 2013 text, which would complicate the nature of the original story about Cotton’s transfer as well as refocus attention on it, was ready to be released to the public on Oct. 29, 2015, five days before the election. Dalton held it back for further review – then went on vacation. “We are not aware of any legitimate reason” for withholding the record, Cappel wrote. It took another attorney in the office to discover – or possibly be told about – the records and move them toward release, 10 days after the election.

How much more information is being concealed? Cappel concluded that “some number” of documents were withheld or redacted based on attorney-client privilege. The investigator tried several times to figure out a way to respect the privilege while having access to the information, and “it is our understanding that the Mayor declined our requests based on the advice of counsel. At the time of this report, we don’t know the full scope or general content of documents that have been withheld from us or redacted.”

In addition, many records that are considered responsive to requests filed are still being reviewed for release. And Cappel concluded that officials stopped keeping notes of significant events, in order to avoid creating a document that might someday be public.

“The absence of documentation appears to have been deliberate to avoid creating a record of Ms. Cotton’s complaints and Chief Straub’s inappropriate behavior,” Cappel wrote. “The absence of documentation also appears to be a common practice within the Mayor’s Administration.”

Coming in Part 2: Just how red does a red flag have to be before someone at City Hall notices?

Shawn Vestal can be reached at (509) 459-5431 or shawnv@spokesman.com. Follow him on Twitter at @vestal13.