Newport woman, 89, going to Malawi for three-month mission

Ruth Calkins, 89, pictured in her Newport, Wash., home on March 16, will spend her summer in Malawi in Africa helping local people create handicrafts. She lived in Africa and other places around the world when her husband worked for USAID. (Jesse Tinsley / The Spokesman-Review)Buy a print of this photo

NEWPORT – Africa is always on Ruth Calkins’ mind – the people, the poverty, the AIDS epidemic.

That’s why the 89-year-old Newport woman is traveling to Malawi in May to start a craft program for teenage girls with AIDS and their mothers and caregivers. She’s bringing her dachshund Max and bags of craft supplies – paper, cloth, batting for quilts, hardware for earrings and necklaces – because many of these items are unavailable in one of Africa’s poorest nations.

“It’s not a question of being brave,” Calkins said. “It’s a question of being stubborn. I have this idea and I’m going to follow through with it.”

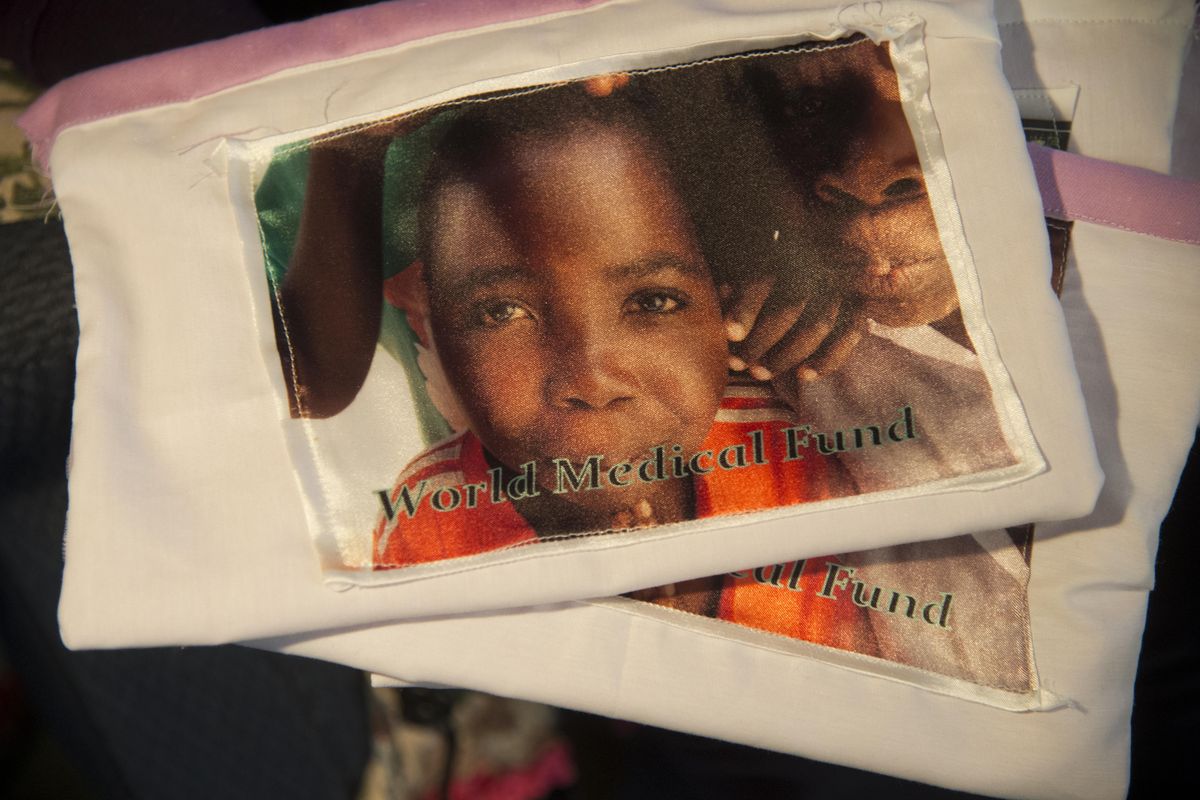

Calkins will spend three months in Nkhotakota, a market town on the shores of Lake Malawi (also called Lake Nyasa) in the center of the southeast African country that borders Mozambique. She will stay in the nurses’ quarters at the headquarters of the World Medical Fund, a medical charity that Calkins has been associated with for nearly 20 years.

Her Newport home is the headquarters for World Medical Fund USA. She serves as secretary for the charity that brings medical aid to children in the bush, sometimes with the clinics set up under a tree, serving as many as 150 children a day. WMF pioneered treatment of children with AIDS.

This is her third trip to Malawi, but the first where she has a mission of creating a way to help raise money for WMF. Also part of her mission: to provide employment for the teenagers and women, who often live on $1 a day.

The plan is to have teenage girls from the area roll and twist colorful paper, stiffened with shellac, into earrings, ornaments and other items such as the colorful lanyard that holds Calkins’ eye glasses around her neck. She made the lanyard as a prototype.

In the afternoon, the girls’ mothers and caregivers (many of the mothers have died from AIDS, Calkins said) will quilt wall hangings from African fabrics and perhaps use photos of Lake Malawi to decorate tote bags and T-shirts. Calkins is in the process of creating a website to sell the Malawi creations to people in the United States, Britain and elsewhere.

Calkins proposes paying the women $1 for two hours’ work. She wants 50 percent of the proceeds to go to WMF, while 25 percent goes to the women and 25 percent goes toward supplies.

During her three-month stay, Calkins intends to train the women and also find someone local to take over management of the program and website so it becomes a sustainable source of income.

Michael Burt, the CEO for World Medical Fund, said Calkins’ proposal is an interesting concept because it provides self-development for the teenagers and women while also helping raise “urgently needed funds” for the organization that relies entirely on donations.

“It will be a challenging three months for her, living in rural Malawi (with her dog) and teaching people, many of whom will not have received any formal education,” Burt wrote in an email from his home base in Norfolk, England. “Ruth is funding this trip entirely from her own resources, and I greatly admire her for her drive and determination to help these poor people.”

Calkins isn’t new to Africa. She lived and raised five children in Nigeria for 10 years in the 1960s and ’70s while her first husband worked for the U.S. Agency of International Development, designing grain bins that kept rats from the corn. After he died in 1974, Calkins remarried. The couple retired to Newport to be closer to his children.

When Calkins learned of the HIV and AIDS epidemic in Africa and all the orphaned children, she took action and set up a donation website.

“It hit me so hard,” she said. “I knew how poor these people were.”

That led her to finding Burt online and learning of his efforts to start WMF in sub-Saharan Africa. WMF’s first project was in 1998 when it was believed that witchcraft caused AIDS. According to the WMF website, the orphaned children of those who died of AIDS “were chased from the villages with people throwing stones at them.” The WMF’s community-based model has had great success and was cited by UNICEF as the ideal model for community-based support.

Nearly 15 years later, the two partners haven’t yet met in person, but Calkins hopes to see Burt this summer in Malawi.

Calkins is unsure where the idea for the craft shop originated, other than she wanted to help the women and the WMF financially but in a more sustainable way than a donation or short volunteer mission. Calkins is now all about action, planning, planning and more planning before she leaves May 27.

Calkins, who is in good health except for a troublesome sciatic nerve, dismisses any talk of age. She has work to do. Besides, she said it’s easier to travel when you are old because she gets a wheelchair at the airport and people are more accommodating.

She’s more worried about getting Max’s paperwork approved when her flight arrives in Ethiopia. And then, once in Malawi, she’ll need to find treadle sewing machines, which are powered by a foot pedal, because electricity is sketchy in Nkhotakota.

“My first reaction when Ruth proposed the idea was alarm!” Burt wrote. “That a person of her age would take on such a formidable challenge, face the inherent risks of an environment where malaria and other tropical killer diseases are endemic – but on reflection, I remembered Ruth is Ruth and a great survivor and I was delighted to give my full support.”