Projects to increase, improve routes for cyclists gain support in Spokane

Cyclists pedal across the suspension bridge above Spokane Falls on Sunday. (Kathy Plonka)Buy a print of this photo

Pavement first came to Spokane in 1893, thanks to cyclists.

The path was about 5 feet wide and ran next to Broadway Avenue. Unlike the road it paralleled, the bike path was graded, graveled, covered with cinder rock and flattened with a 6-ton roller until it was hard as stone.

The city’s bicycle tax, passed in 1889, paid for the work, and the path was used exclusively by wheelmen, as they were called. It took four more years for Howard Street to be paved, and though it came well after the city’s first bike lane, this was the first “official” paved road in Spokane.

There’s no report detailing the length of the Broadway bike path, but one thing’s clear: This year will see much more pavement built or reserved for cyclists in Spokane than during that first paved year, and likely more than any year since.

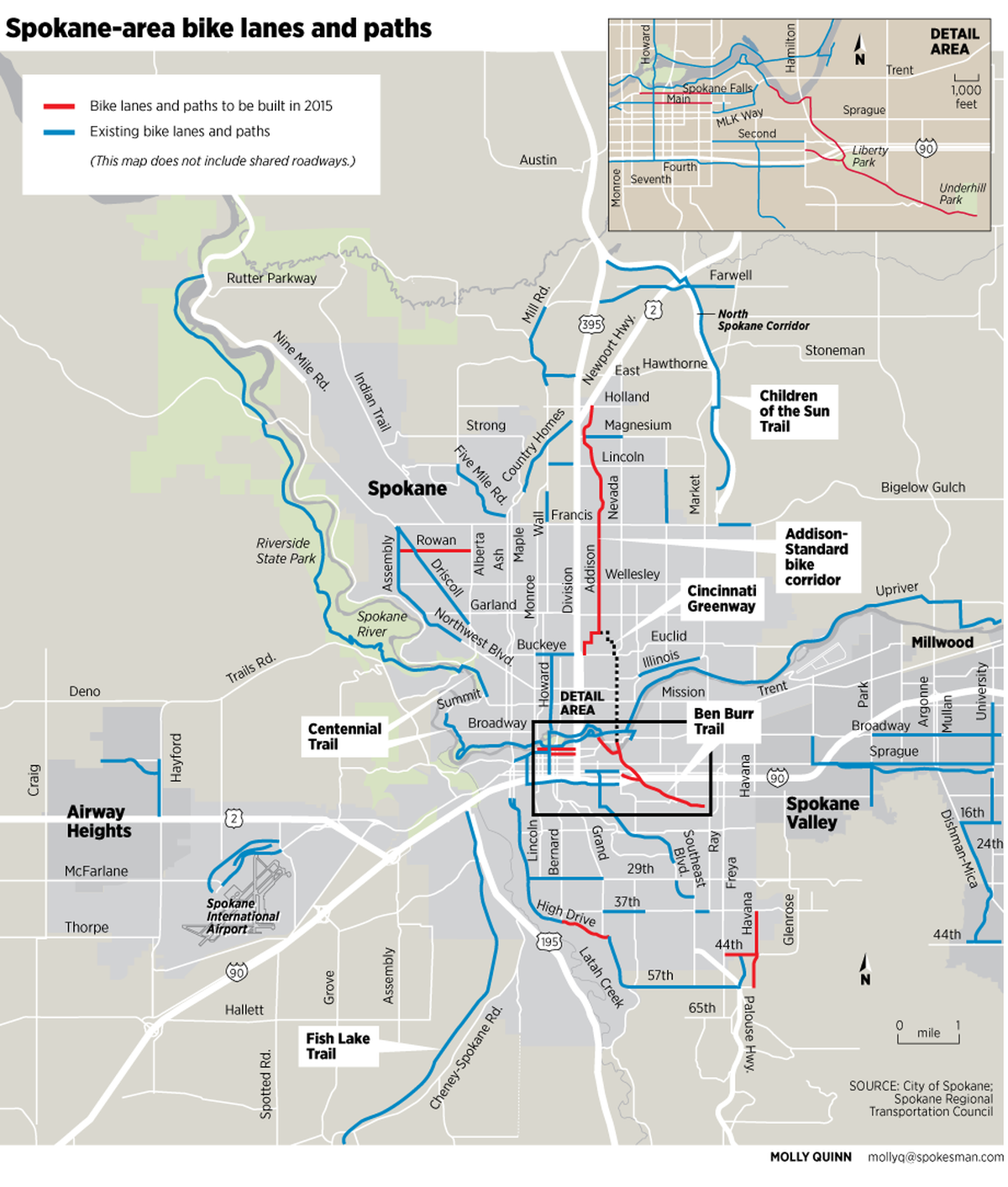

In all, 2015 will see about 13 miles of new dedicated lanes or separated paths, adding to the more than 100 miles of bikeways within city limits.

This spring and summer, the East Central neighborhood’s Ben Burr Trail will be widened, paved and connected to the Centennial Trail. The nearly 5-mile Addison-Standard bike corridor will create an easy route from near Gonzaga University to the northernmost part of town. New bike lanes will be added to a handful of roads being rebuilt this year as part of the 20-year street levy voters approved in November.

On Monday, the Spokane City Council laid the groundwork for upcoming work by updating the city’s Master Bike Plan, the guiding document for bike facilities. But work outside the city is also contributing to the flurry of cycling infrastructure. At a recent “bike summit” of cycling advocates, city engineers and planners in Olympia, the state’s transportation secretary, Lynn Peterson, endorsed innovative national standards for integrating bikeways into city plans.

Peterson’s wholehearted encouragement surprised many participants, including Spokane City Councilman Jon Snyder, an outspoken bike advocate.

Though Snyder praised Peterson’s encouragement of bike planning – as well as the work happening at the city – he said Spokane has far to go.

“There has definitely been a ramping up of projects and there’s a lot of good stuff going on,” Snyder said. “Is it as fast and strong as we need it to be? I would say no. Most of the easy things have been done. We need to start doing the hard stuff. The city has to be bold.”

North-south bikeway

Right now, riding a bike from the Nevada-Lidgerwood neighborhood to East Central is a practice in patience, and not the safest way to spend a Saturday afternoon. But come fall, an almost fully connected and nearly 9-mile route will connect these two parts of Spokane, which are among the most unfriendly for cyclists.

The northern part of the route is the Addison-Standard bike corridor, a $550,000 project paid for with federal funds, which will install missing bike lanes and provide safe crossings at arterials. The project, which will be completed this summer, will take cyclists from the small Hill N’ Dale Park behind the Home Depot in the north to North Foothills Drive near Addison Street. The route parallels North Division just a few blocks to the east, and will be the city’s first major north-south, dedicated urban bikeway.

The corridor’s southern end, at North Foothills Drive, is near the beginning of the planned Cincinnati Greenway. The greenway, the first of three the city is considering designating in coming years, is a street with little, and slow-moving, vehicular traffic that prioritizes bicycle and pedestrian traffic.

The Cincinnati Greenway has no funding yet, but it’s estimated the 1.7-mile route will cost about $400,000, which includes installing new sidewalks, crosswalks at arterial intersections and curb ramps that meet federal disability rules.

When the Cincinnati Greenway is complete, it will join the Addison-Standard corridor to the Ben Burr Trail.

The $1 million plan to improve the trail – which is currently a quiet, graveled path connecting Underhill and Liberty parks – angered some East Central neighborhood residents. They referred to the planned trail as a “bike freeway,” and said the project would destroy the character of the trail. The trail project is being paid for in part with a federal grant aimed at reducing air pollution by decreasing the number of cars on the road.

Still, the effort to make a safe connection across town is important to encouraging more cycling, said Eve Nelson, a senior transportation planner with the Spokane Regional Transportation Council, who pointed to the proposed greenway as an especially good way to get people on bikes.

“There were no greenways in the city of Spokane’s bike plan. That’s a new idea for our region,” Nelson said. “That is the type of a facility that attracts the nonexperts.”

Other potential greenways would run along Walton Avenue and Manito Boulevard. The South Hill Coalition, which includes the six neighborhoods on the hill, has drafted a handful of potential greenway routes crisscrossing the south end of town, including one along 33rd Avenue and down Arthur Street.

Completing downtown

With new roads come new bike lanes, thanks to the successful street levy and the “integrated streets” policy leading the charge. West Rowan Avenue, High Drive, South Havana Street and East Indiana Avenue will get bike lanes this construction season, adding about 4 miles of bike lanes to the city.

At the center of this growing web of bikeways is the Downtown Bicycle Network. The $224,000 project will create a loop of bike lanes circling downtown, and will be done this summer. The bike lane near Auntie’s Bookstore on Main will use a “buffered” bike lane, the first of its kind in the city. Instead of just one stripe of paint separating cyclists from traffic, two stripes separated by 3 feet of blank space will add an extra cushion and a bit of reassurance for riders.

It’s a small shift, but it represents a new way of thinking about road design for Spokane. Brandon Blankenagel, a senior engineer with the city, said in years past, the city required some car lanes to be 20 feet wide, with 14-foot turn lanes.

“That’s what the bike plan was originally up against,” Blankenagel said. As ideas shift about traffic-calming measures and how much capacity a road can handle, city planners and engineers are looking for new ways to design cities.

Minneapolis or Seattle

Arguments for increased bike facilities usually rest on talk of pollution, reliance on foreign oil, an obese nation and crippling traffic jams.

But Nelson, with the transportation council, said it could come down to lack of transportation funding. After years of dwindling infrastructure funds, the U.S. Conference on Mayors launched a massive campaign last week to push Congress to pass a surface transportation bill and increase funding for local and state transportation projects.

“What can we afford to maintain, really, is what we’re looking at as an agency,” said Nelson, noting that bike facilities are much cheaper to build and maintain than roads. “And how can we sustain it.”

Snyder agreed with Nelson, pointing to two northern cities that could serve as examples for Spokane: Minneapolis and Seattle.

Minneapolis winters are brutal, yet the city is considered one of the best for bikes in the country. It has a bicycle highway, and a recent count netted nearly 40,000 cyclists, a 73 percent increase since 2007.

Seattle, hilly and congested, can’t handle its downtown traffic, forcing 70 percent to commute by something other than a car. Mayor Ed Murray recently proposed a $900 million transportation levy, nearly all of it aimed at infrastructure not used by cars. One estimate says the plan would complete half of the city’s ambitious bike plan.

Snyder, whose commuter bike can be seen outside City Hall most days, praised Minneapolis and warned that Spokane was in danger of following Seattle’s congested, reactive path.

“We’re headed in Seattle’s direction, and we need to be prepared,” he said. “Seattle is not a great example. They’re playing catch-up now. Their congestion went crazy before they reacted to it. I don’t want us having to do a $900 million catch-up levy. On the other hand, that (bike highway) in Minneapolis was hard to do. But they did it and now people love it.”