Moving water, moving images

Gurche’s river photographs explore ways of seeing

The longer photographer Charles Gurche looks at a patch of water – say, a 10-by-10-foot piece of the Spokane River – the more he sees.

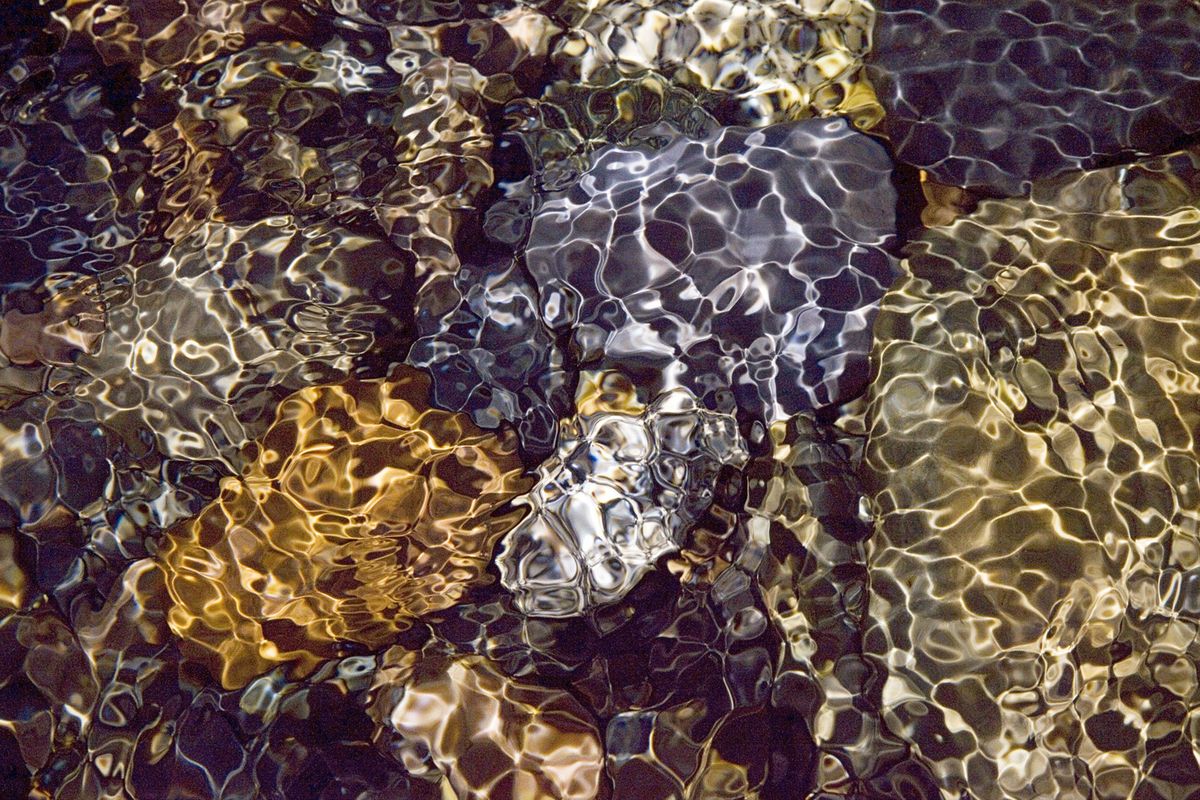

Forms, colors and patterns emerge on the river’s surface, as variable as the light, the wind and the stones under the water.

An exhibit opening tonight in the gallery space at Dodson’s Jewelers offers a look at Gurche’s work, a dozen photos of the Spokane River that veer into the abstract – the photographer’s own interpretation of a local landmark.

The show is an outgrowth of a project Gurche did for Spokane Riverkeeper, a Center for Justice program devoted to the watershed’s health. Charged with documenting scenes and landscapes on the river for the program to use with its own materials, he spent part of each season in 2014 documenting the waterway.

For the region’s inhabitants, Riverkeeper Jerry White said, the river provides an “aesthetic experience, and that’s a really important thing to put out there, too, as a riverkeeper – just the sheer beauty of looking at the pattern of light and water.”

Gurche, 61, of Spokane, is a landscape photographer whose work has appeared hundreds of times in National Geographic, Sierra Club, Audubon and other publications, including his own 15 books of nature photography.

Gurche, who grew up near Kansas City, said he’s been looking closely at wild places since he was a child, traveling with his family on vacations north to Lake Michigan or south to the Ozark Mountains.

A self-taught photographer, Gurche said Freeman Patterson’s “Photography and the Art of Seeing” served as a guide as he learned to create his own vision.

In recent years, water has helped him expand that vision.

Gurche’s website features a gallery devoted to water images. While the subjects in some are recognizable as streams and rivers – “Sunrise on the Missouri River” might make you wish you’d been there that morning – others are abstract, otherworldly and painterly. “Ice,” made in Washington, looks amoebic. A photograph of sycamore trunks reflected in a creek in Virginia could be an impressionist’s canvas.

The Spokane River images at Dodson’s fall under two categories: reflection and refraction.

To see what the water mirrored back, he’d hunker beneath small rapids. When waterfowl passed by him, he’d shoot in their wake, recording the changes on the water.

For images of refraction – the bending of light as it passes through water, changing the way we see the shapes underneath – he’d wade into shallow areas to peer at the stony surfaces underneath.

Now, Gurche said, he’s working to expand his vision as an artist. That means, on the job, striving to “clear everything else out of the brain except for the actual form and color that you’re with … and to get in touch with what’s happening inside as you look at design and composition. If you can get in touch with what’s stirring inside, then you can really get somewhere.”