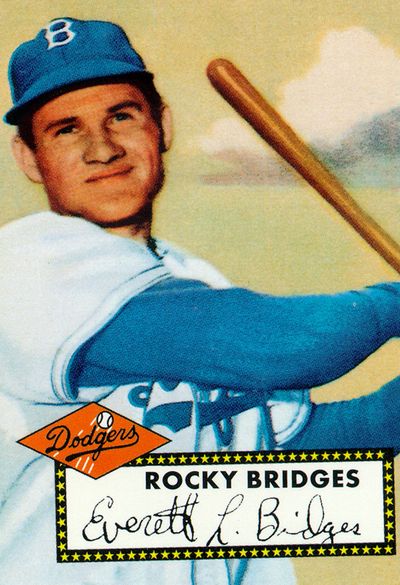

Former Dodger, Rocky Bridges, dies in Coeur d’Alene

Rocky Bridges may have missed his calling.

A journeyman Major League baseball player and former minor league manager, Bridges was the king of the one-liner.

One time while having dinner at a fancy restaurant, Bridges was asked by a waiter if he’d like some escargot.

“No, I’d prefer fast food,” Bridges quipped.

Everett Lamar “Rocky” Bridges, 87, who lived in Coeur d’Alene, passed away early Tuesday from natural causes.

Bridges’ professional career began in 1951 with the Brooklyn Dodgers and ended in 1961. He played for seven teams in 11 seasons.

His longest stretch with one team was with Cincinnati for four years. He once said he feared being traded to Cincinnati because “I can’t spell it.”

He was selected for the All-Star game when he was with the Washington Senators in 1958. His final season in 1961 was the California Angels’ inaugural season.

Bridges was signed by the Dodgers in 1947. He played shortstop, third base and second base, and was a backup to Jackie Robinson with the Dodgers.

He had a career batting average of .247 and never hit more than five home runs or stole more than six bases in a season.

Bridges was far from done with baseball when he retired from the Angels in 1961. He got into coaching, mostly managing in the minors, for the next three decades. He won 1,300 games in the minors.

In one of the last interviews he gave to a national newspaper, Bridges told Jerry Crowe of the Los Angeles Times in July, 2011: “I managed, I scouted, I coached, I did everything. I was like a house without toilets. I was uncanny.”

Bridges was born in Refugio, Texas, but raised in Long Beach, Calif. He moved his family to Coeur d’Alene in 1970.

He was preceded in death by his wife, Mary, who died in 2008. He is survived by a daughter, Melinda Galbraith, Coeur d’Alene; Lance, who lives in Post Falls; Cory, who lives in Coeur d’Alene; and John, who lives in Idaho Falls, Idaho. He has multiple grandchildren.

University High graduate Casey Parsons, 60, remembers fondly playing three years for Bridges for the Giants’ farm team in Phoenix.

“He was one of the most colorful managers I played for,” Parsons said. “He had a unique ability about him. He never put pressure on anybody. At times I put a lot of pressure on myself. He did a terrific job of calming me.”

Parsons said Bridges loved to do crossword puzzles.

“He was a crossword genius,” Parsons said. “People don’t realize what a baseball guy he was. And he had such a wit about him.”

Bridges’ son, Lance, will always cherish the fact that his dad balanced baseball with being a father.

“He had a great love for the game but he was also a fantastic dad, coach and a friend. He was always teaching us boys and (sister) how to play the game.”

He laughed when he recalled one of his father’s many stories.

“My dad used to say ‘there are three things the average man thinks he can do better than everybody else’,” Lance said. “Build a fire, run a motel and manage a baseball team.”

In his playing career, Bridges had a chin that could stop any erratic, bouncing ground ball. Writer Harry Cheadle described Bridges this way: “… had a head like a concrete block, a gap between his front teeth, and a face that looked like it had been hit a few times after the mouth had downed a few too many drinks.”

Bridges was a big fan of chewing tobacco. Years ago he was featured in a story in Sports Illustrated about chewing tobacco.

“He always had a big wad of chewing tobacco wedged in his cheek and the expression of a man bracing himself for bad news,” Cheadle went on to write. “He looked, in other words, like a ballplayer.”

In Crowe’s story, he told the story Bridges shared about concocting a diet drink. “You mix two jiggers of Scotch to one jigger of Metrecal. So far I’ve lost five pounds and my driver’s license.”

Bridges never owned a cell phone and he read all the newspapers he could get his hands on.

His youngest son, John, who teaches in Idaho Falls, followed his dad’s passion for the sport and played at Eastern Washington University.

“He was an unbelievable wordsmith,” John said.

John Bridges’ collegiate career came near the end of his father’s coaching career.

“I think dad saw me play once at Eastern,” he said. “You never ever felt like he was gone. Baseball was his job and it greatly influenced his kids. He’d take off in February and it was like we didn’t skip a beat when he’d show up at the end of the year.”