Grant will fund work to reduce wildfire risk in northeast Washington

Steve Parker had two reactions to last summer’s wildfires in Central Washington: a deep empathy for the people who lost homes and businesses, followed by the thought, “What if that happened here?”

It wasn’t hard for the Stevens County commissioner to imagine a catastrophic wildfire sweeping through northeast Washington.

In northern Stevens County, where he lives, Parker has walked through forests so crowded and unhealthy that “it looked like a dead zone,” he said. “If a fire started, it would burn all the way to the Canadian border.”

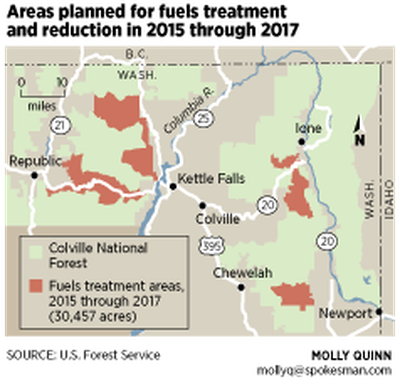

Over the next three years, a federal grant will help reduce the risk of explosive fires on 30,000 acres near rural communities in Stevens, Ferry and Pend Oreille counties. The work also will protect critical infrastructure, such as transmission lines.

The Colville National Forest is getting $2.5 million to accelerate ongoing thinning of dense stands of trees and to reintroduce fire to the forest through controlled burns. Up to $3 million also will be available for similar restoration work on adjacent state and private lands over the three years.

“We all know that fire doesn’t respect political boundaries on a map,” said Franklin Pemberton, a Colville National Forest spokesman.

The collaborative program, called the Landscape Restoration Partnership, is intended to prevent wildfires from spreading across jurisdictions, he said. And when wildfires do occur, less fuel in the forest will result in smaller, patchier blazes, according to land managers.

A century of fire suppression has altered northeast Washington’s forests, said Scott Brogan, a Forest Service silviculturist. Dry, ponderosa pine sites evolved with small, creeping fires that frequently burned through the forest, clearing out the small trees and underbrush. Mature pines, and even Douglas firs, had thick enough bark to survive most of those fires, Brogan said.

Excluding fire has led to denser forests, prone to disease and insect attacks. When the stands eventually burn, the wildfires are more destructive.

The restoration work will convert those drier sites to more natural conditions by clearing out small trees and brush, Brogan said. After the thinning and burning, the stands will be back to about 40 to 60 trees per acre, instead of 200, he said.

“We’re trying to take it back to what it would have looked like a long time ago,” Pemberton said.

Studies show that treated acres are more resilient to wildfires, said Susan Prichard, a University of Washington research scientist.

After the Tri-Pod fire complex burned 175,000 acres in north-central Washington in 2006, Prichard studied how the restored acres had fared.

Where tree stands were thinned, fires tended to stay on the ground, which made them easier to put out, she said. Where the trees were thinned and the underbrush was burned before the wildfires hit, a higher percentage of trees survived the blaze.

“There were these green islands in a sea of black,” she said.

Prichard is eager to study last summer’s Carlton Complex fires for comparison. Severe weather conditions, with 100-degree temperatures and gusting winds, fueled a fast-moving blaze that destroyed more in its path. But there are still things to be learned about how the fuel treatments performed under catastrophic conditions, she said.

About 9.5 million acres of dry forests in Washington and Oregon need thinning to restore it to more natural conditions, according to a recent study by the Nature Conservancy and the U.S. Forest Service.

About 40 percent of the 1.1 million-acre Colville National Forest is at risk for high rates of tree mortality over the next 15 years, according to a recent Forest Service designation. Over the past five years, about 63,000 acres of the forest have been treated.

That’s a start but more work remains, said Parker, the Stevens County commissioner.

“Four hundred thousand acres needs to treated, and treated aggressively,” he said. “We’ve let things get way out of control.”