‘Halloween’ still sets bar for well-crafted horror

I wonder what might have happened had John Carpenter’s seminal 1978 horror masterpiece “Halloween” been released under its original title – “The Babysitter Murders.”

Would it still be hailed as a high point in its genre with such a lurid name, or would it have been instantly dismissed by critics and lumped in with all the cheap, exploitative trash that was filling drive-ins and second-run theaters at the time? After all, “Halloween” is such a catchy, evocative, moody title. “The Babysitter Murders”? Not so much.

Although it didn’t invent the slasher genre (that auspicious achievement is generally credited to Mario Bava’s 1964 giallo “Blood and Black Lace”), “Halloween” served as a template for the slasher boom of the late ’70s and early ’80s, although the rip-offs and cash-ins it inspired swapped Carpenter’s impeccable sense of suspense and rich shot compositions with shameless gore.

“Halloween,” which plays on the big screen at the Bing tonight with a restored print, remains a gripping piece of horror filmmaking, and what’s amazing to consider is that Carpenter only had two features under his belt – the sci-fi cheapie “Dark Star” (co-written by and starring future “Alien” scribe Dan O’Bannon) and the grisly grindhouse classic “Assault on Precinct 13” – when it went into production.

Carpenter’s direction is remarkably confident and assured in every respect: He employs negative space and shadow to generate suspense, he uses inference and expectation in lieu of explicit violence, and his own haunting synth-driven musical score builds and crescendos in all the right places. Critics at the time were sort of blindsided by “Halloween,” since they went in expecting a dumb hack-and-slash gorefest and instead got an honest-to-god movie .

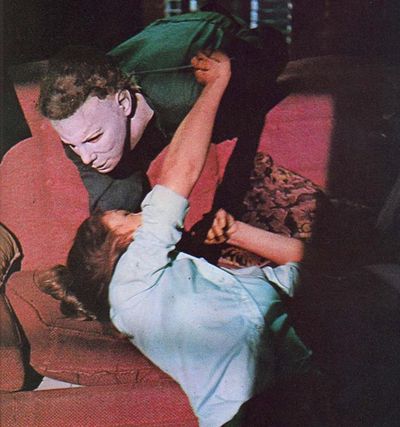

The premise is brilliant in its simplicity. The film opens with a famous POV shot (cleverly concealed to look like a single uninterrupted take) in which a young boy named Michael Myers fatally stabs his older sister. Myers escapes from his institution 15 years later, dons a featureless white mask and starts stalking and murdering a group of teenagers (including Jamie Lee Curtis in her first movie) in his Illinois hometown on Halloween night.

The film was made for just $325,000 (that’s roughly $1.2 million in 2014 dollars, which is still a pittance) and was dumped into just a handful of theaters in ’78. But strong reviews and word-of-mouth led to a worldwide gross of $70 million, making “Halloween” one of the most profitable independent movies of all time.

Its success, coupled with the big earnings of 1980’s “Friday the 13th,” led to studios churning out an endless string of lifeless slashers – “Prom Night,” “Terror Train,” “My Bloody Valentine,” “The Prowler” and “The Burning,” not to mention the increasingly disappointing “Halloween” sequels. With a few exceptions (Wes Craven’s self-aware “A Nightmare on Elm Street” and “Scream,” for example), it seems as if the bones of the slasher genre have been picked clean.

As the “Halloween” series progressed, logic and continuity went right out the window. Myers’ backstory grew so convoluted and contradictory that alternate timelines actually exist – for instance, 1998’s “Halloween: H2O,” the seventh entry in the series, simply pretends as if events in the previous three films had never happened. It’s too complicated to care about, and the character was robbed of his initial impact.

Michael Myers is, I think, scarier the less we know about him. Carpenter establishes the bare minimum of character development in that first film – he’s psychotic, he’s on the loose, he can’t be stopped – and that’s all we need. Giving Michael Myers a backstory is like giving the shark in “Jaws” a plausible M.O. Does it really matter why he’s evil, or how he came to be that way?

By not giving us an answer, “Halloween” still retains an unshakeable horror. It’s crafted like an especially effective haunted house, in which every corner has the potential to hide something terrifying.