Spokane County Commission candidates at odds over urban growth boundary

The future of a neighborhood in north Spokane County has become one of the most debated topics in this year’s race for County Commission.

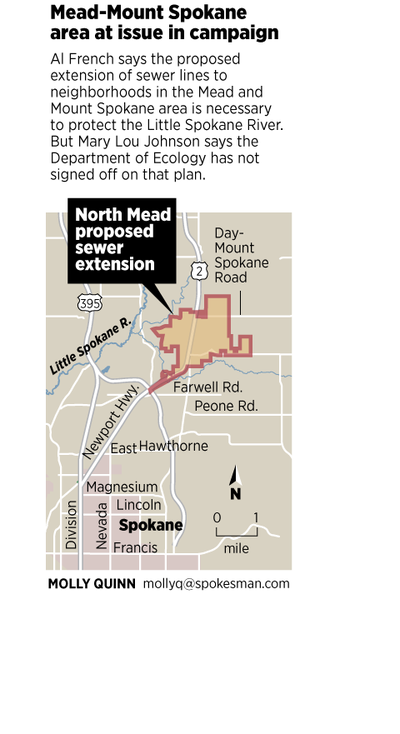

Al French and his fellow Republican Commissioner Todd Mielke say expanding the urban growth boundary to include the area along U.S. Highway 2 is necessary to protect the Little Spokane River from sewage runoff seeping from aging septic tanks. The extension of the growth boundary, a designation that enables governments to extend services such as sewer lines, would solve a problem before it gets out of control, they said.

“This is the difference between being a leader and reacting to a situation,” French said.

But Mary Lou Johnson, a Democrat who is challenging French in the November election, says commissioners are using the ecological issue as a smoke screen to enable commercial development. Expanding the growth boundary also enables zoning changes that could bring in denser development, which Johnson would prefer to see within city limits.

Attorney Rick Eichstaedt, who has represented in courts and legal hearings a coalition of neighborhood members who consistently challenge the county on its land-use policies, said the environmental concerns raised by Mielke and French are an attempt to explain a decision that’s already been made.

“I think they’re grasping at straws,” Eichstaedt said.

Mielke told state legislators at a hearing in Olympia last month that he’s discussed sewage seepage in the Mount Spokane neighborhood with the Department of Ecology for almost a decade.

The commissioner said representatives of that agency asked the county to include the neighborhood in the urban growth boundary “so that those areas can be sewered, because once those systems fail – and they’re going on 40 years now – there is no room for another drain field.”

In an interview this week, Mielke said there was no single document indicating the Ecology Department’s support of the plan, but that the request was made informally following a discussion of how best to clean up the Little Spokane River.

Johnson has seized upon this issue in the campaign and pointed to several comments French has made indicating the Ecology Department’s support of the expansion. French has said even without the department’s explicit support, including the neighborhood within areas where sewer can be extended serves the goals of the organization by protecting groundwater. Mielke echoes this position.

“I’m supposed to anticipate needs within planning,” Mielke said. Changes to areas where a county will allow denser development are scheduled to occur every decade. Mielke said septic systems near the end of their life cycle would not be relieved for at least another 10 years if the area is not added in the latest update, set for approval in 2017.

Eichstaedt points to state law, which enables counties to extend sewers to areas other than those designated for urban development if evidence shows there is a threat to “basic public health and safety and the environment.”

But Mielke said that approach to extending sewer lines, in essence declaring an emergency, is not smart planning.

“That’s a bad way to install infrastructure,” Mielke said.

Mountainside Middle School in Mead, which would fall within the expanded urban growth boundary, has been using an onsite wastewater treatment facility since 2008. Mielke said the sewer extension would allow the district to stop spending needless money on chemicals for the facility, which was designed to handle more wastewater than it is taking in.

“Kids in junior high school no longer shower after gym class,” said Ned Wendle, facilities director for the district. He said the facility could handle “a small community” and would likely be sold if Mountainside were hooked to the sewer line.

The district spends $100,000 annually to run the facility, Wendle said.

The closest the Ecology Department has come to weighing in on the urban growth issue on paper is a 2012 report about phosphorous levels reaching Lake Spokane from the Little Spokane River. In that report, the department recommends monitoring area septic systems every one to three years to ensure they are functioning properly. It makes no recommendation to extend sewer lines, though the department generally favors this approach.

Grant Pfeifer, who leads the Eastern Washington office of the Ecology Department, said his agency does not typically weigh in on land-use issues, but agreed that sewers had been discussed as a way to relieve pollution in the Little Spokane River.

“It’s not our role to rule or endorse a policy,” Pfeifer said. “We generally make recommendations.”

Water politics

At a September debate, French said the county was working with the Ecology Department to bring sewers to the Mount Spokane area by extending the urban growth boundary.

“We’re doing it in partnership with the Department of Ecology, so that we can extend sewer up to the north and get those residences and businesses that are on septic tanks over the aquifer, off of the aquifer,” French said.

But at a debate Monday at Central Valley High School, French said the decision to extend the boundary was made independent of the department.

“They did not require us to do this,” French said.

French said in a subsequent interview he considers the Ecology Department a partner despite the lack of a written agreement, in addition to other local governments and agencies.

“It’s all part of a combined effort to clean up the river,” French said.

Johnson said French’s statements misrepresented the Ecology Department’s position.

“What we need to know are the actual facts,” Johnson said. “It has been suggested that if we, in fact, sewer that area, that’s going to make it very easy for developers to develop there.”

French said the argument that taxpayers would pay for the extension of services to the benefit of developers was “categorically wrong.”

“The developer pays for water, sewer and streets,” he said.

Johnson said she supports efforts to clean the aquifer, but hasn’t seen enough evidence that eliminating septic tanks in the area would have a significant effect on pollutants in the groundwater. She’s filed a public records request with the county for information about pollutants in the watershed, she said.

“What I’m hoping to get are answers,” Johnson said. “What is the real motivation behind this?”