Department of Ecology drafts flow rules for Spokane River

Hundreds of millions of dollars have been spent to improve the Spokane River’s water quality.

Now state regulators say it’s time to ensure that the urban waterway has enough flow to support healthy fish populations and recreational uses.

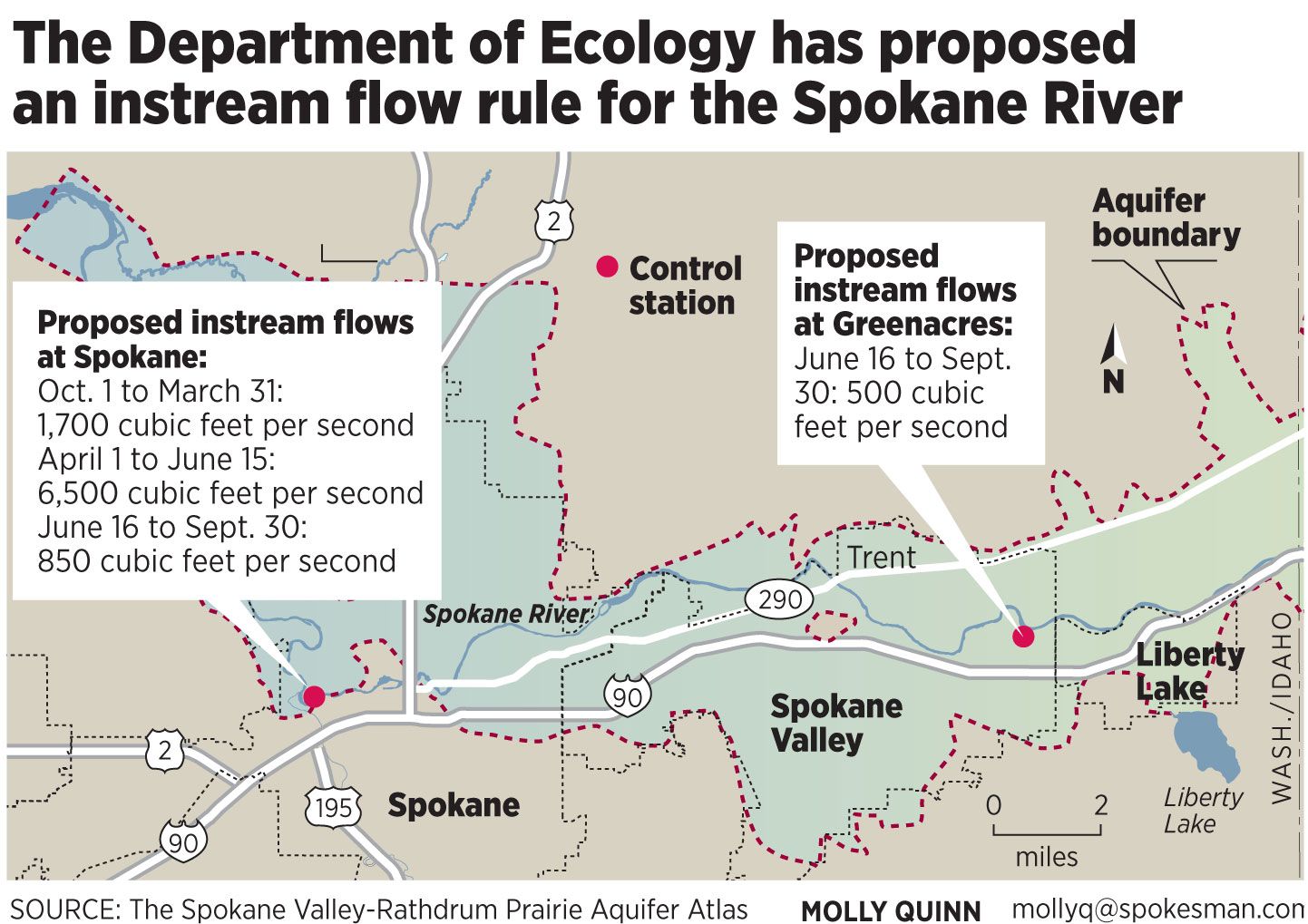

To help achieve that goal, the state Department of Ecology has drafted rules for how much water should flow in the river. They would apply to Spokane County and part of Stevens County.

“It’s kind of like a water right for the public,” said Guy Gregory, a hydrogeologist for the Ecology Department. “It protects the surface water uses the public has an interest in.”

Public comment will be accepted on the proposal through Nov. 7, with a decision expected by January. But critics already say the agency’s proposal isn’t adequate.

“For whatever reason, they’re low-balling it, and that’s not a good thing,” said Rachael Paschal Osborn, a water attorney representing the Sierra Club and the Center for Environmental Law and Policy.

The proposed flow rules would vary by season, peaking at 6,500 cubic feet per second in late spring where the river roars through downtown Spokane. That would taper to 850 cubic feet per second during the summer. Each cubic foot of water is about 7 1/2 gallons. Gregory said the flow rules won’t guarantee the Spokane River always would have that much water.

That’s because the rules won’t affect existing water right holders, who can continue to withdraw the water they’re permitted to take. But if a new user applied for a water right, state regulators would evaluate whether the Spokane River and its connected aquifer had enough water to meet flow rules before allowing new withdrawals.

Environmental groups believe the flows proposed by the Ecology Department will penalize the region in future conflicts with Idaho over water.

“This rule is staking out Washington state’s position with Idaho,” said Osborn, the water attorney. “At some point there’s going to have to be a division of water, so it’s important to get this right.”

The proposed flows, she said, “give a lot of water away to Idaho.”

Rafters also think the proposed flows are too low.

“That’s not close to being acceptable,” Paul Delaney, spokesman for the Northwest Whitewater Association, said of the proposed summer flows. At flows less than 1,000 cubic feet per second, “you can barely get a little cataraft through the left side of the Devil’s Toenail” at Riverside State Park, Delaney said.

Jerry White, the Spokane Riverkeeper, said he supports the Ecology Department’s efforts to set minimum flows for the river. “It will be critical over the next 20 to 30 years” as the climate warms and demand for water increases, he said.

However, the department’s proposed summer flow “seems very low,” said White, who still is studying the issue. He also wants to ensure that river flows through mid-June are high enough to protect young redband trout, a native fish.

Washington’s proposed flow rule comes as neighboring Idaho nears the end of a yearslong water adjudication for its portion of the Coeur d’Alene-Spokane River basin. That effort, expected to wrap up in 2017, is cataloging valid water withdrawals to protect the future rights of Idaho water users.

The Washington Legislature hasn’t designated money for a Spokane River adjudication on its side of the state line. But creating a flow rule will give Washington an official position for future litigation or negotiations, said Keith Stoffel, an Ecology Department water resources manager.

Stoffel said proposed flows are based on extensive habitat studies for rainbow trout and mountain whitefish, two key fish species in the river. Ecology officials also reviewed a previous study of whitewater rafting on the Spokane River but opted to base the flows on the quantifiable fish research, which Stoffel said had a better chance of withstanding legal challenges.

“Rather than padding the flow, we think we’ve set a legally defensible flow that will stand up in court,” he said.

“There are always folks who want more water for the river,” Stoffel added, “and there are always folks who want to take more water out of the river to use. We’re kind of in between those numbers.”

But Osborn, the water attorney, said rafting is among the recreational uses that the flow rules are designed to protect.

Keeping more water in the river for rafters would benefit fish, too, Osborn said. In other parts of the state, she said, the department has adopted rules designed to protect high runoff during wet years. Fish production shot up during those years, she said.

Osborn said she’s afraid the proposed flows would allow new water withdrawals from the Spokane River and the Spokane Valley-Rathdrum Prairie Aquifer. That’s a possibility, according to Stoffel.

The department has a backlog of 24 applications for new water withdrawals. Most are from small water districts or developers, with a few applications for irrigating golf courses.

The applications were put on hold during a 2007 study, which confirmed that water drawn from the aquifer decreased flows in the river. The Ecology Department also wanted to establish the river’s flow before considering the applications.

Neither the city of Spokane nor other large water districts have applications pending. Collectively, they have rights to about twice as much water as their customers currently use, said Gregory at Ecology. Those rights would be senior to any flow rule adopted by the agency.

“We believe there is enough water for local purveyors” well into the future, Gregory said.