Rich Landers: Clif Bar decision shows personal nature of assessing risk

The risk in cutting-edge outdoor pursuits is in the spotlight this month because of a bold decision by an energy food company.

Clif Bar dropped sponsorship of rock-climbing sensation Alex Honnold and four other athletes because the California organic energy food maker says it’s no longer comfortable with the death-defying extremes of certain sports.

Contracts have been cancelled with top names in BASE jumping, high-lining and free-solo climbing (without the safety of a rope and belayer).

The announcement came as the annual Banff Mountain Film Festival was revving up audiences with adventure films featuring these and other sports with commercial pucker power.

Some climbing enthusiasts vowed product boycotts in support of inspirational and gifted athletes who lift their sports to higher levels.

But the trend in reaction quickly balanced with kudos for a company bold enough to step back from the edge.

“Maybe it was handled poorly, but the dad in me has gotten increasingly uncomfortable with this kind of climbing – and also the Red Bull rampage,” Greg Bain, a reader, posted on the Outside Magazine site. He singled out the beverage company that fuels body-breaking competition in muscle- and motor-powered sports such as free-skiing, snowmobiling and a bull riding.

“Too much risk,” Bain said. “And I am a lifelong avid outdoorsman, including kayaking and mountain biking.”

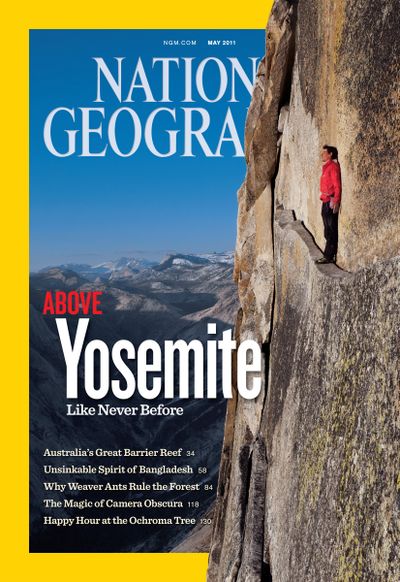

Honnold, 29, climbed his way to 60 Minutes and the cover of National Geographic magazine for films of his cool, daring unroped ascents of huge walls. He responded with similar poise in a New York Times op-ed piece.

“Of course, I was disappointed to be dropped by a sponsor…,” he wrote. “Still, I couldn’t help but understand their point of view.”

In a statement after the furor erupted, Clif Bar acknowledged that risk is inherent in adventure, adding:

“We appreciate that assessing risk is a very personal decision. This isn’t about drawing a line for the sport or limiting athletes from pursuing their passions. We’re drawing the line for ourselves.”

Honnold seized the connection:

“In essence, that’s the same way I feel when free soloing,” he wrote.

“I draw the lines for myself; sponsors don’t have any bearing on my choices or my analysis of risk.”

He distinguished himself from, say, a pro golfer who contracts with a sponsor to show up at certain tournaments.

On the other hand, he’s made a career by sharing his world-class skills and steady nerves with camera crews. In a SquareSpace commercial that aired during the World Series, Honnold free-soloed an exposed Yosemite route called Heaven, where one lapse spelled certain death.

“Soloing appeals to me for a variety of reasons: the feeling of mastery that comes from taking on a big challenge, the sheer simplicity of the movement, the experience of being in such an exposed position,” Honnold wrote in the Times. “Those reasons are a powerful enough motivation for me to take certain risks. But it’s a personal decision, and one that I consider carefully before any serious ascent.”

This issue of risk has been hitting home since the first cliff dweller left the cave.

“This is nothing new, really,” said Chris Kopczynski, a Spokane mountaineer whose résumé includes Everest and other significant climbs around the globe. “People have always told climbers they were crazy.”

Kopczynski’s not fretting for free-climbers. Modern cameras afford them great opportunity in the free-market system.

“These people are so incredibly good, doing things we thought impossible just a few years ago; they won’t be ignored,” Kopczynski said.

“I’m watching this with envy,” he chuckled. “The only sponsor I ever had was my mother.”

No one lives with risk more intimately than a mom, says Rebecca Mack of Spokane.

“We raised our four boys to be adventuresome, to experience the extraordinary pleasures of adventure in the outdoors, and now it keeps me up at night,” she said.

Her 20-something son Henry has run her through the gamut of heartache and hope.

“He’s a commercial fisherman, one of the most dangerous occupations,” she said. “And in his off-season he surfs, climbs and goes backcountry skiing in high-risk avalanche zones.

“He’s really done a good job of trying to allay my concerns by telling me that even after they’ve skinned up a mountain, climbing midnight to 7 a.m., they assess the risk. He claims that if they test the snow and decide it’s too risky, they’ll strap the skis on their backs and walk down to safer areas rather than enjoy the thrill of their original goal.”

But Mack said she freaked when one of Henry’s friends was killed in an avalanche while backcountry skiing in Oregon last winter. “I love him so much,” she said, reliving the pain. She’s buoyed by signs of maturity in her son’s outlook.

“Henry’s been successful in commercial fishing,” she said. “But he feels a bit guilty and responsible for inspiring his brothers to get jobs on Alaska boats last year. I heard them talking about things like, ‘If you lose an arm fishing you’ll never be able to climb ice or pow ski again.’”

Mack says her boys would accuse Clif Bar of “embracing wimpdom” by dropping sponsorship of extreme athletes. But she finds comfort in one factor she injects into her sons’ adventurous lifestyles.

“We talk about risk a lot in our family,” she said. “I hope every family does. It’s through those discussions that Henry has convinced me he’d rather live than die.”

Contact Rich Landers at (509) 459-5508 or email richl@spokesman.com.