Wolf 47 works full-time for Washington wildlife researchers

GPS signal helps state identify new Ruby Creek wolf pack

Conventional wisdom in northeastern Washington suggests that gray wolves are lurking everywhere – that is, until you try to catch one.

Capturing a wolf for research ranges from dangerous to tedious, depending on whether the tool is a helicopter or a leg-hold trap. Either way, success rates are low because the target is mobile, wary and still rare even in the corner of the state where wolves have repopulated the most ground.

“We’re not trappers; we’re wildlife biologists,” said Scott Becker, the Fish and Wildlife Department’s wolf biologist. He was driving into the Colville National Forest on July 15, which turned out to be a banner day for Washington wolf research.

“There’s so much more to what we’re doing than trapping, but this is a key part,” he said on the way to joining his two seasonal wolf specialists to check traps for anything that might have been caught overnight. “Getting a collar on a wolf is the ticket to a ton of information for years.”

The state designates three or more biologists who try to put transmitting collars on wolves to monitor their movements and estimate their populations.

Wolves aren’t trapped and tranquilized during cold or hot weather to avoid stress that could kill them. March is an active month for the trappers, but the effort is suspended in April as wolves are denning.

When the biologists begin looking for opportunities in May, they try to avoid denning and rendezvous areas to keep from snagging a pup. By summer, trapping can be done anywhere there’s persistent sign.

“Wolves are moving all over by summer,” Becker said. “We like to follow up on hard evidence, especially photographs of two animals together. That means a high probability they may stick around and not just be passing through.”

The wolf program’s 2013 seasonal trappers, Gabe Spence of Twisp, Wash., and Trent Roussin of Minnesota, already had been working the area from Colville east to the Pend Oreille River starting in June based on wolf-sighting reports.

“Tips from the public are a big help to us,” Becker said. “We came here because we got several reports. That’s how most new packs have been identified. Mostly we want to put collars on lone wolves or wolves in pairs to see if they’re forming new packs.”

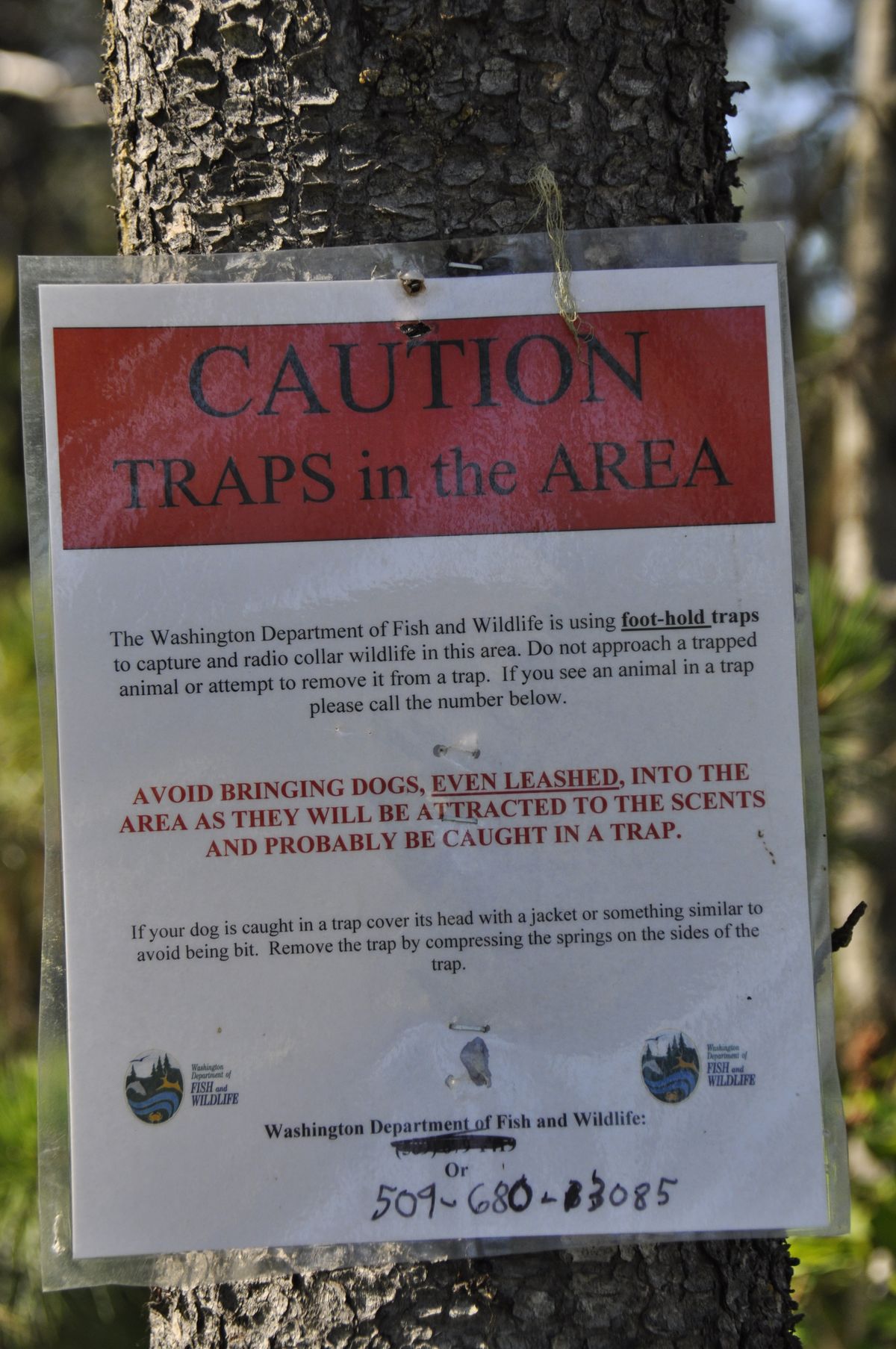

Once they found fresh sign – tracks and scats – concentrated in an area, they rigged up remote cameras, posted signs warning of traps and began looking for patterns and experimenting with trap sets.

Before becoming Washington’s wolf biologist two years ago, Becker cut his teeth on capturing wolves and grizzly bears with state and federal wildlife agencies working in Wyoming and Yellowstone National Park.

“I’ve worked with good trappers who devote their lives to the art,” he said. “They’re tight with their secrets. Job security.

“You try to pick up bits and pieces anywhere you can and apply them to your own trial and error,” Becker said noting that while trapping a wolf once is difficult, getting it to step in a trap again is really rare.

“Miss one the first time and you may never catch that wolf,” he said. “You know you’re doing things right if you get a recapture.”

When setting a trap, they might kneel on burlap placed on the ground to minimize contact with the trapping area and disturbance to the trap site.

Becker plucks ponderosa pine needles to use like a broom for brushing duff over the trap to hide it, and then takes the needles with him.

“You try to leave as little of your scent as possible,” he said.

Other considerations include avoiding stock and domestic animals. The traps can’t be remote because they must be regularly checked, but they must be away from areas that invite human tampering.

They use scents such as coyote urine to attract wolves rather than food that would attract creatures they don’t want in their traps, such as eagles and bears.

Patience needs to be in bold letters on the job description.

“We were finding a lot of sign here a couple of weeks ago but had to pull out during a stretch of 90-plus-degree weather,” Spence said. “Now we’re back.”

They had found wolf scats in the middle of a national forest livestock grazing allotment southeast of Ione near Ruby Creek. This was less than a year after the agency had made the last-resort decision to eliminate the Wedge Pack farther north after the wolves had repeatedly attacked and killed cattle.

But no livestock had been reported injured by wolves near Ruby Creek.

“Best I can tell, the one or maybe two wolves in here are living on small game like ground squirrels,” Spence said.

“Wolves scavenge a lot more than people think,” Becker said. “They’re quite opportunistic.”

After catching three wolves in the Teanaway region last spring, the trapping crew had gone four months without a capture.

“Wolves are especially difficult because their ranges are big,” Becker said. “The wolf that made a track here yesterday could be 20 miles away today.”

Gray wolves are the lean but hungry marathoners of the wildlife world. “They’ll rest in the heat of the day, but otherwise they’re on the move in a lope,” he said.

The chances of finding a wolf in a trap that day were very low, Becker said as the three men drove in separate pickups to check traps set within sight of forest roads.

But the biologists beat the odds that morning.

“We got one,” Spence said on the radio.

The men converged within minutes and prepared to tranquilize a black wolf alternating between hiding and lunging occasionally in vain attempts to pull its right front foot out of the trap.

With the trap anchored to a stake, the tables were turned on the wolf, which was being threatened and false-charged to within a few feet by three black cows. Their curious calves had walked over to see what this black thing was and the cows followed to defend them.

Roussin shooed the cattle away as Becker loaded a syringe on the end of a long pole with the proper drug dose. The wolf crouched low to the ground as Roussin approached from one side as a distraction.

But it whirled about-face with terrifying speed, power and slashing teeth when Spence poked it in the rump with the needle.

The men backed away. Minutes later, the wolf was immobile.

It was quickly gathered on a tarp and taken to shady area for a work-up. An anal thermometer was monitored throughout the process. The wolf was doused with water to keep its body temperature around 100 degrees.

“Yearling female, about 15 months,” Becker said, estimating the age by the wear on its remarkably white teeth. “Appears to be in good condition,” he added as he combed through its thin summer coat with his fingers.

Before slipping a protective cover over its face, lubricant was dripped into the wolf’s fiery yellow eyes, which remained open and unblinking from the drug.

Blood samples were taken and measurements made as the biologists ticked through their checklist.

“It neck is 16 1/2 inches – same as mine,” Spence said as Becker wrote down the numbers.

Bulbous feet punctuated the long, lean legs. The foot that had been clamped in the trap’s rubber-edged, off-set jaws showed minor swelling but no damage to the skin.

“If you find a canine track that’s over 4 inches long out here, it’s likely a wolf,” Becker said. “Smaller than that, it’s something else.”

A GPS collar was fitted on the wolf’s neck. An electronic identification chip was implanted under its skin.

Spence attached a red tag into its ear, taking care to avoid veins when punching holes, and saving the punched out flesh for possible DNA testing.

The tag read No. 47.

The wolf was lifted on a scale: “68 pounds,” Becker said. “Males average 90-110 pounds and females average 70-90 pounds, but she looks good. Summer is one of the leanest times of the year for a wolf.

“Her size makes me think she’s not yet at the age where she’d be good at surviving on her own. It’s just a clue that she might be working with another wolf.”

The heaviest U.S. wolf on record was 147 pounds, captured in Yellowstone, he said as they packed up their gear. “But it was caught on an elk kill and could have had 15-20 pounds of meat in its belly.

Wolf 47 was moved again to get farther away from the cattle so it could peacefully regain its senses.

“She’s licking her lips and nose,” Becker pointed out as they set it in the shade of small trees one hour after it had been tranquilized. “That’s the first sign a wolf is coming to.”

Ruby Creek Wolf 47, the only wolf captured in a trap in the northeast corner of the state last year, became one of 11 in Washington with active collars in 2013 providing daily information to biologists.

While a few Washington-collared wolves have strayed hundreds of miles into Canada, the Ruby Creek wolf has kept a more normal home range near Ione that overlaps with the Smackout Pack, where she originated, biologists say.

Wolf 47’s GPS signal allowed biologists to monitor its movements and document that it was, as Becker and Spence figured, working with another wolf. The collar made it relatively easy to bring in a helicopter this winter to capture the other wolf – another female.

Monitoring led to the confirmation of another wolf pack in Washington, one of four new packs in the state documented in 2013, bringing the total to 13 packs.

That’s one more step closer to delisting the gray wolf from Washington’s endangered species list.