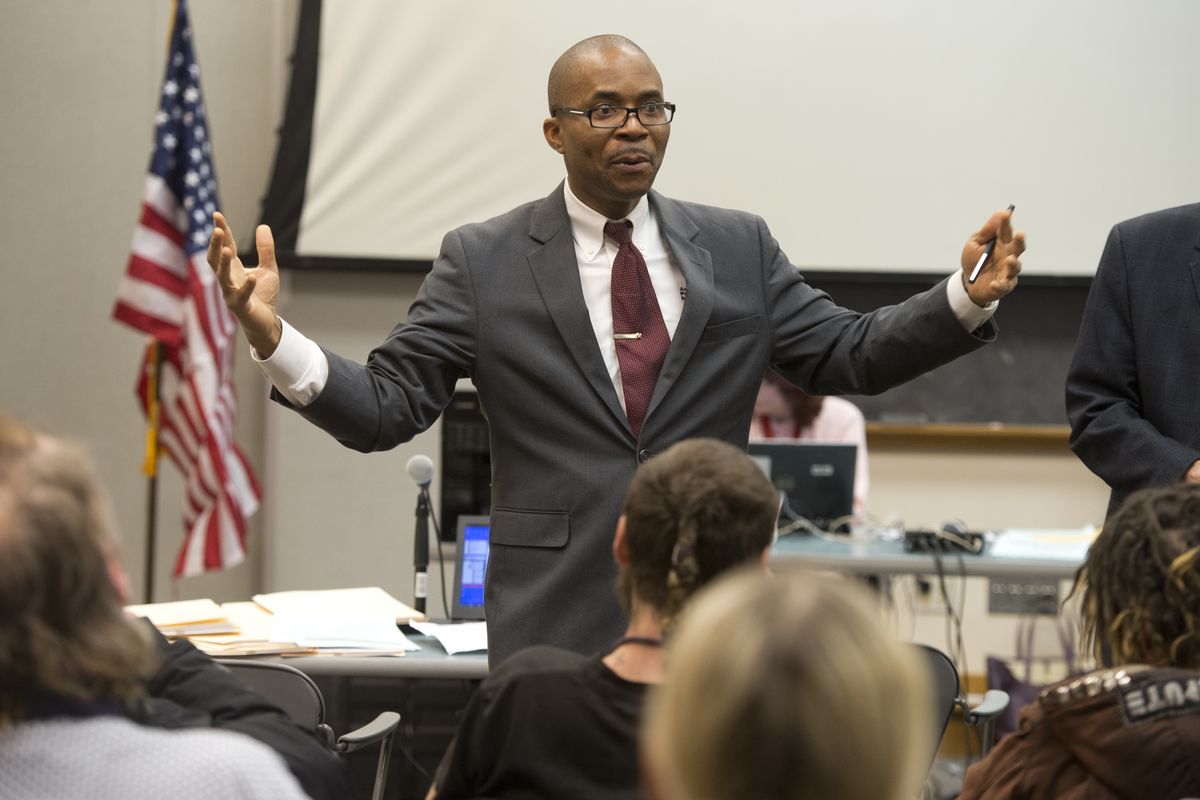

Nigerian-born attorney gives back

Like most of the teens in his village, Nigerian-born Francis Adewale loved spending time with the American Peace Corps volunteers working there.

“You know,” he says, “hanging out with Americans is cool in Africa.”

One day, he says, one of the volunteers began writing something on a blackboard that Adewale thought was poetry.

“We hold these truths to be self-evident,” the American wrote, “that all men are created equal …”

“He was writing it without even having to look at any book,” Adewale recalls. “And he was saying it with gusto. It was like he was speaking deep from his heart. You could see that he really passionately believed in this.”

It prompted young Adewale, then just the equivalent of a high school junior, to ask about the passage’s significance. And the answer he received would change his life.

“He said to me, ‘Well, it’s more than poetry, Francis,’ ” Adewale says. “ ‘It is the basis on which my country was founded.’ ”

That, though, is when the conversation took an unexpected turn.

“He said ‘Do you know, the people who wrote this beautiful verse, at the time they owned slaves? People like you would have been slave to them.’ ”

The key, the volunteer stressed, was that these men, these Founding Fathers who were soldiers and farmers and lawyers, “were looking at a bigger future than where they were. They had one goal: They wanted a better, just society for themselves.”

“He said, ‘America is not about how much armaments and how much ammunition we have. It’s about the value that we aspire to be.’ ”

Adewale, now in his mid-40s and an attorney in the Spokane Public Defender’s office, dates his desire to be a lawyer from that day. His job involves the handling of cases for clients who are mostly indigent or low-income. He is the primary defense attorney for Spokane’s Community Court, a program founded in March that is designed to handle the cases of chronic nonviolent offenders.

In his spare time, Adewale runs a free legal clinic at the Spokane Dream Center church, and he serves on the board of directors for Refugee Connections Spokane, an organization that links immigrants with area support groups.

“Francis’ contributions to the community are extremely valuable because he seeks to give a voice to those without one,” says Spokane City Prosecutor Justin Bingham. “There are plenty of attorneys who help large corporations and other monied interests. Francis has chosen a different road, one which requires him to fight for people whose personal struggles would go unnoticed but for his actions.”

One of Adewale’s more notable contributions involved the American Law and Justice Workshop for Refugees that he coordinated in October with Megan Ballard, a professor at Gonzaga Law School. Sponsored in part by Refugee Connections, the workshop was designed to educate immigrants about the U.S. legal system and to stress how the system might differ from that of their native country.

“Francis has vision about what we need to do in Spokane for it to be a community for everybody,” says Susan Hales, executive director of Refugee Connections. “And then he sees the different actions that have to take place and the parties that have to be involved. And when he raises the issue, because of his understanding at such a gut level about what the need is and how to get there, people instantly rally around him.”

Adewale’s vision of community evolved over years and included a switch of continents. After having left his village of Ilesa, he earned a law degree in 1990 from Lagos’ Nigerian Law School and went to practice maritime law.

But though he made a comfortable living, Adewale was troubled by the ongoing problems that his country faced – first by a military dictatorship and later by a corrupt civilian government. He responded as a student and then as a young attorney by joining the protest movement, which made him a target for potential violence.

So when a friend applied for a U.S. Visa lottery program in his name, and he was accepted, Adewale decided to emigrate.

“It came at the right time, when I really needed it,” he says. “They were hunting everybody down, trying to kill us.”

He arrived in Washington, D.C., in 2000 but soon learned that Washington state offered a special deal: Lawyers who have practiced for seven years in common-law countries are eligible to sit for the state’s bar exam. Adewale studied while working in D.C. as a security guard, and he passed on his first attempt.

Through another Nigerian, he learned about Spokane. And when the opportunity came to work here as a public defender, he stopped applying to Seattle maritime firms.

The support he received during his first few months, and which continued, convinced Adewale that Spokane was where he wanted to raise his family, which includes his wife and five children.

“Everybody says, ‘Oh, you have five kids. How do you do it?’ ” he says. “But it’s not a burden. It’s not a burden at all. This society gave me so much, you know, and I want to be able to give back. It’s a joy, actually, to be in a position to do so.”

That joy, Adewale knows, was formed those many years ago by a Peace Corps volunteer with a vision not of America as it necessarily is but certainly as it always has aspired to be.

Dan Webster