Apparent suicide highlights legal difficulties of treating mentally ill

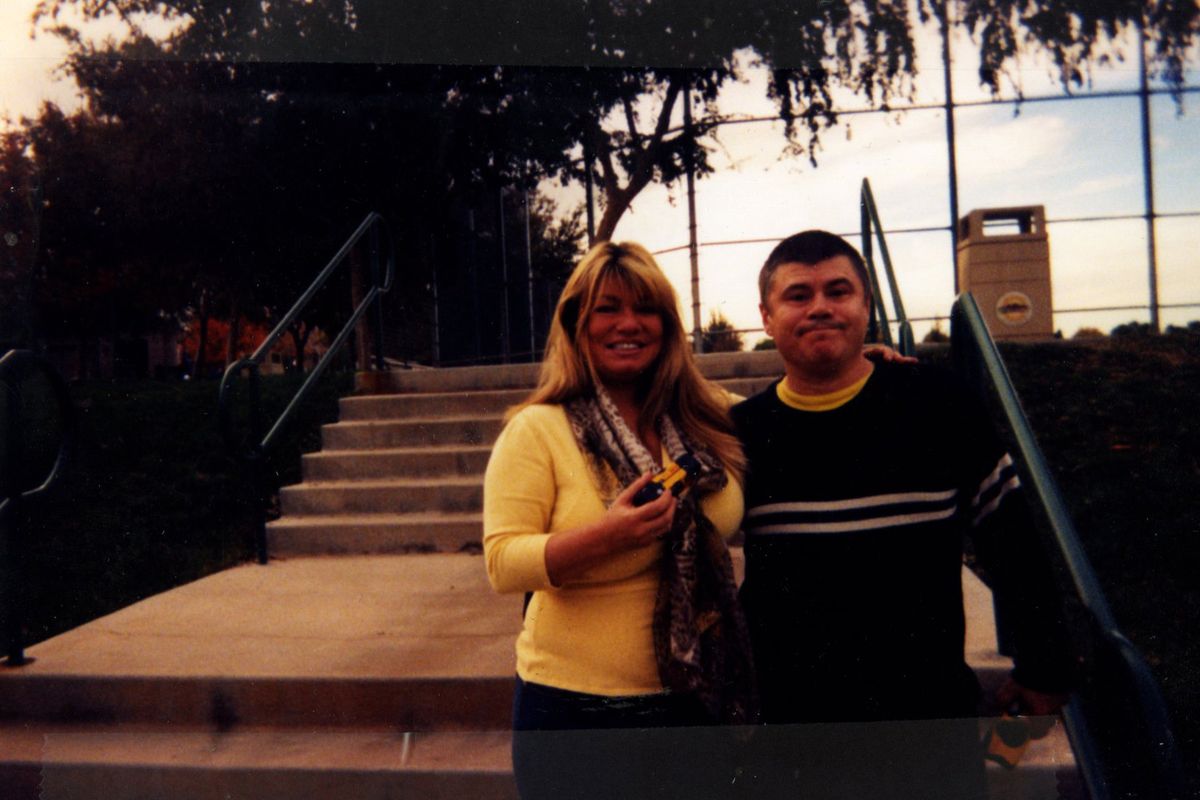

Michael McCann’s life ended at age 52 in one of the few places he found serenity.

McCann, who was diagnosed with schizophrenia in his mid-20s, was swept away by the waters of the Spokane River on the night of April 12.

Police responded to the apparent suicide shortly after witnesses saw McCann venture dangerously close to the water near the Monroe Street Bridge. He was curiously waving goodbye.

McCann backed up into the water and, predictably, the current overpowered him.

Several fire units and boats searched the river, but it was too late; the search ended after six hours.

A month later, his body was found on a private dock near Nine Mile Falls.

His family in Wisconsin believes there were missed opportunities for social workers and mental health professionals to help McCann, whose manic symptoms washed over him a month before he walked into the river. But his case also illustrates the challenges of dealing with adults who have mental illness, where a patient’s civil and privacy rights aren’t abrogated unless he or she has proven to be a danger to themselves or someone else.

Erratic behavior began months before

Months before his death, McCann had stopped taking Haldol, a prescription drug that treats mental and emotional disorders, believing he was fine without it, according to medical records provided by his family. The records say McCann had begun “thinking more about the things he hasn’t been able to accomplish due to his mental illness.”

Late in March, his family believed he’d also stopped taking three other medications to treat his schizophrenia, depression and insomnia. A clinician from Frontier Behavioral Health, which provides inpatient and outpatient mental health care, visited McCann at the time and confirmed this to be true.

Medical records show that he was “vague and evasive” about having suicidal thoughts during that clinical visit. His landlord, Adam Reynolds, noticed he was acting differently and told McCann’s family. McCann had started banging on other residents’ doors and pacing around outside, the landlord said.

Meanwhile, McCann’s mother, Carol McCann, and his sister, Kelly McCann, said they hadn’t been able to reach Michael, with their calls going straight to voice mail. So they called Frontier – every day for two or three weeks, Carol McCann said – to try to make sure he was being taken care of, hoping he would be medically evaluated, hospitalized and given medicine to treat his manic symptoms.

“We had been trying to get help for him,” Kelly McCann said. “We made so many phone calls, and they weren’t doing anything about it.”

But Jeff Thomas, CEO of Frontier Behavioral Health, said there isn’t much anyone can do to force someone to take medications if they’re not a danger to themselves or someone else.

“If someone isn’t taking their medication, that’s not cause for action in itself,” said Thomas, who stressed that he wasn’t commenting on McCann’s specific case. “If that threshold is not met, their civil rights cannot be overridden.”

The Frontier staff recommended that the agency’s “hospital diversion team” contact McCann for an assessment. That team decided he didn’t need any further outreach, believing he had started taking his medications again.

But his erratic behavior continued, and on April 10, McCann started a fire on the side of his apartment building. He told police he “wanted to cook a roast.”

Police arrested him on a charge of reckless burning in the second degree. In doing so, they noted that he was wearing multiple shirts and pants; he told officers he had to, in case someone came into his building and he had to leave quickly.

When McCann arrived at the jail, he was asked if he would harm himself; he replied he didn’t know but he had thought about it, said Spokane County sheriff’s Detective Lyle Johnston, who investigated his death.

Frontier Behavioral Health consulted McCann while he was in jail to determine if he was fit to be released. McCann appeared somewhat disheveled, according to medical records, although the social worker noted that he was difficult to view through a small window in a door. It’s unclear whether McCann was evaluated personally, or if the extent of the evaluation was through his cell door; Frontier officials declined to talk specifically about his case.

He told the Frontier caseworker that he had taken his medication the day before he was arrested. McCann reportedly said at the time, “Man, these drugs are making me mad,” and asked if they could be changed, according to medical records. The caseworker told him to address the concerns at a follow-up appointment three days later. The records report that McCann said he’d go home, take his medicine and “maybe drink some coffee.”

Frontier, which coordinates mental health care with the jail, decided that Michael was not a danger to himself or others and approved his release.

Carol McCann believes releasing her son was a deadly mistake.

“We trusted them to help him and it’s just unbelievable. Unbelievable,” she said.

McCann’s family contends he was clearly a threat to himself, after repeatedly being unclear about whether he had been thinking about suicide in the days leading up to his death.

“If they thought he was bad enough to arrest, they should have put him in the hospital,” she said.

She notes that her son’s social worker told her he served as many as 83 clients at a time.

McCann’s landlord at Woodstone Apartments put an unofficial hold on his apartment, wanting him to have a full medical evaluation before returning. Legally, though, the landlord could not stop McCann from returning, and it’s unclear whether McCann was notified of the hold and thought he was unable to return. Reynolds, the landlord, said he did not see McCann return and would not have stopped him from doing so after talking to him.

But family members believe that the hold placed on the apartment may have stopped McCann from returning to his home after his release. Instead, perhaps feeling unwelcome at his complex and with nowhere else go to, they say, he wandered toward the river he loved.

Apartment manager cast in role of counselor

There have been increased efforts to integrate the lives of people with mental illness into the community through low-income and subsidized housing. Yet this independence can sometimes mean people aren’t getting the care they need.

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development Section 811 program is designed to help people with mental and physical disabilities live independently by providing housing for those who might not be considered eligible by most landlords.

Spokane County has targeted funding to support people with disabilities and special needs in recent years, according to Christine Barada, director of the Spokane County Regional Support Network. For the mentally ill, the goal is to provide a community away from the streets.

Carol McCann said such services provided her son “as near a normal life as he could have,” adding, “years ago people like Mike would have been in a mental institution.”

In some cases, however, the apartment manager is cast into the role of counselor.

Donnell McQuistion, manager at Manito Gardens apartment complex, which has subsidized housing for people with mental disabilities, said she has received extensive training on handling mental health issues. Even so, she said her hands often are tied when she notices someone is off their medication.

“Either they have to get arrested, or they have to put themselves into a psychiatric center,” McQuistion said.

The only thing managers can do is monitor residents.

Gene DiRe, associate director at Catholic Charities, said it’s a civil rights issue.

“The challenge is balancing a person’s individual liberties with other factors pertaining to mental health,” DiRe said.

Elizabeth Kelley, a criminal defense attorney who frequently represents people who have a mental disability, said the tension between civil rights and treatment is profound.

She said advocates of treatment believe it’s more important that a person who is not taking medication be given care they need so they are not a threat to themselves. Others believe they should have the freedom to make their own decision when it comes to treatment.

“Proponents of civil liberties are of the mind that people with disabilities are capable of making the decision, that they are adults – they have the right to their own bodily integrity,” Kelley said.

Families only have “the power of persuasion” if they’re worried about an adult with mental illness and want to have that person hospitalized, unless the person demonstrates dangerous behavior or a loss of cognitive control, she said.

Reynolds, McCann’s landlord at Woodstone Apartments not far from Division and Francis in north Spokane, said McCann had always been respectful. But even when his manic symptoms became apparent, there was nothing Reynolds could do until McCann set the building on fire, Reynolds said.

“I think (Michael) needed some specific counseling that involved a lot more attention,” Reynolds said.

Jerry Schwab, director of counseling and case management services for Catholic Charities, said that ideally, more counseling would be offered to people with mental disabilities while they live independently.

“There’s clearly a gap,” Schwab said. But “there is hope on the way,” he said. Catholic Charities has a new project to provide subsidized housing for the homeless and people who are mentally ill, which will include mental health caseworkers on site who will have frequent contact with their clients.

He said the pilot project, which currently is nameless, has been in the works for months. A building has been identified but isn’t being disclosed just yet.

It will house 21 units for the most vulnerable, chronically homeless individuals in the community, who may be abusing drugs or alcohol and who often have mental illness.

He said more housing with on-site case managers would be a “new trend.”

“The hope is that there’s more and more funding available for support services for folks in houses,” Schwab said.

Family often estranged from McCann

McCann had lived successfully with a mental illness for years.

He was raised in Wisconsin and during his 20s, his family often didn’t know where he was for long periods, said his mother, Carol McCann. When he landed in Spokane, though, he easily made friends, he liked the weather and the mental health system took care of him, she said.

Carol McCann said the family did not know how to deal with Michael McCann’s mental illness and that they were often estranged.

“I’m not happy with the way things were in our family,” she said.

She said she and her daughter feel guilty that they didn’t travel to Spokane when they suspected Michael McCann was in distress.

“I wish we lived there and could have had a life with him,” she said.

She’d been impressed with her son’s treatment prior to the last episode. One of his favorite places was the Evergreen Club, part of the Frontier Behavioral Health system that works to find employment for people with mental illness. He made friends there, she said.

And he loved the Spokane River, Carol McCann said. It was his favorite place to go when life was good for him.

“It just might have been that that was the last place he wanted to be,” she said. “Maybe he figured that was his end.”

But she is not sure he really wanted it to end there. He may have been reaching for help while he was by the river, she said.

She said the same thing could have happened to anyone with a mental illness in Spokane.

“They mean something to someone. They’re somebody’s son, somebody’s brother,” she said. She believes the social safety net failed her son.

“They were just letting him float around.”