History on hold

The dispute over Rosa Parks’ estate is keeping the civil rights icon’s belongings out of public view

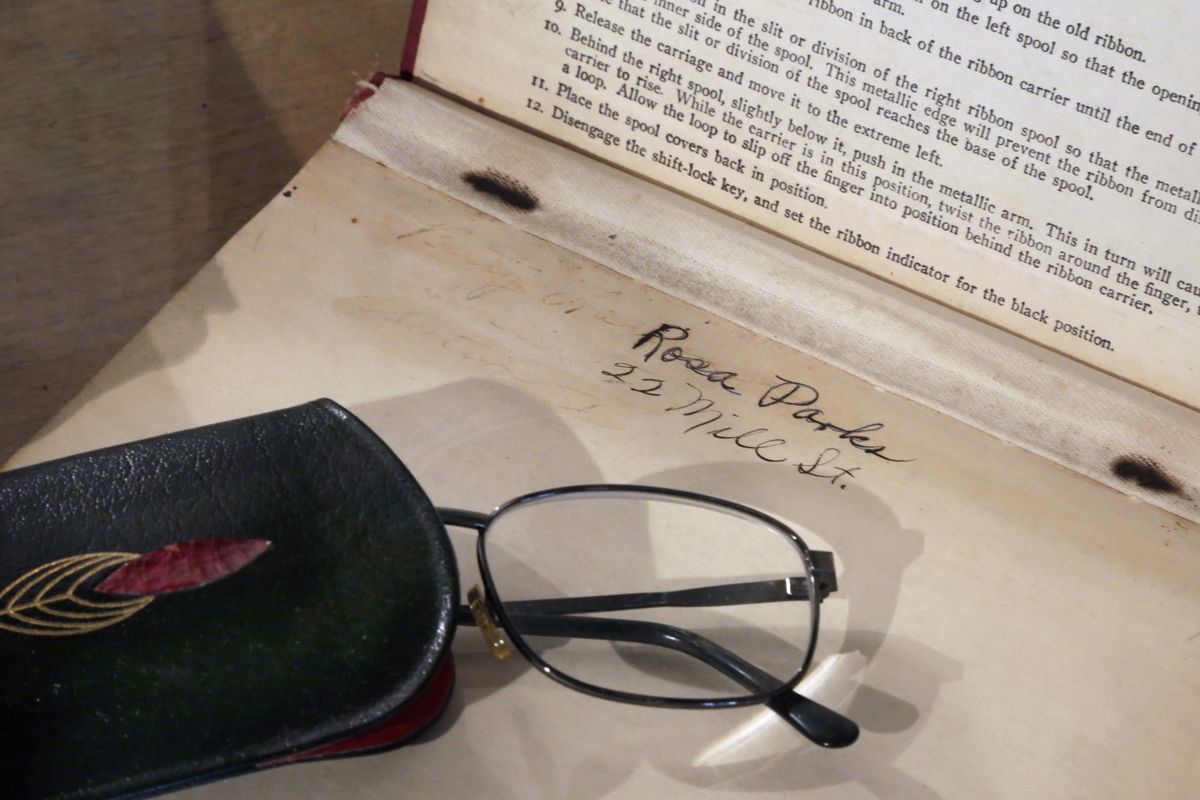

A pair of eyeglasses and a typing textbook are among items that belonged to Rosa Parks now housed at a New York warehouse. (Associated Press)

NEW YORK – At a time when interest in civil rights memorabilia is rekindled, a lifetime’s worth of Rosa Parks’ belongings – among them her Presidential Medal of Freedom – sits in a New York warehouse, unseen and unsold.

Parks’ archives could be worth millions, especially now that 50th anniversaries of the civil rights era are being celebrated and the hunt is on for artifacts to fill a new Smithsonian museum of African-American history.

But a yearslong legal fight between Parks’ heirs and her friends – a dispute similar to the court battle among Martin Luther King Jr.’s heirs – led to the memorabilia being taken away from her home city of Detroit and offered up to the highest bidder.

So far, no high bidder has emerged.

Parks is one of the most beloved women in American history. She became an enduring symbol of the civil rights movement when she refused to cede her seat on a Montgomery, Ala., bus to a white man. That triggered a yearlong bus boycott that helped to dismantle officially sanctioned segregation, and lift King to national prominence.

Because of the fight over Parks’ will, historians, students of the movement and the general public have had no access to items such as her photographs with presidents, her Congressional Gold Medal, a pillbox hat that she may have worn on the Montgomery bus, a signed postcard from King, decades of documents from civil rights meetings, and her ruminations about life in the South as a black woman.

Parks wanted people to see her mementos and learn from her life, said Elaine Steele, a longtime friend who heads the Rosa and Raymond Parks Institute for Self Development, a foundation Parks co-founded in Detroit in 1987.

“In my opinion, it was quite clear what she wanted,” Steele said.

Steele’s lawyer, Steven Cohen, said Parks’ heirs and the institute certainly could come to agreement on sending the artifacts to an appropriate institution “if we could close out the estate and get away from” the probate court. He said he hopes to resolve the matter in six months to a year.

“It will happen,” Cohen said. “But right now we’re hamstrung, because the probate court continues to want to monitor and control our activities. And it shouldn’t.”

Parks, who died in 2005 at age 92, stipulated in her will that the institute bearing her name receive a trove of personal correspondence, papers relating to her work for the Montgomery branch of the NAACP, tributes from presidents and world leaders, school books, family Bibles, clothing and furniture. Her nieces and nephews challenged her will, and her archives were seized by a court; a judge ordered it sold in one lump sale.

King’s belongings also are locked in a legal dispute. King’s sons, Martin Luther King III and Dexter Scott King, want to sell or lease their father’s Nobel Peace Prize medallion and one of his Bibles; King’s daughter, the Rev. Bernice King, opposes such a move. Because of the squabbling, a judge ordered the Bible and prize medal to be held in a safe deposit box controlled by the court until the disagreement can be resolved.

Since 2006, Guernsey’s Auctioneers have kept Parks’ valuables in a New York warehouse, waiting for someone to offer the $8 million to $10 million asking price. By comparison, the city of Atlanta paid $32 million to King’s children for his papers, and the Henry Ford Museum paid $492,000 just for the bus aboard which Parks took her 1955 stand for civil rights.

Rex Ellis, associate director of Curatorial Affairs at the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, thinks Parks’ archives should be in a museum or research facility.

“She was just an extraordinary figure that any student of American history, not African-American history, any student of American history should know and be aware of,” Ellis said.