Hidden pitfalls: Closed North Idaho mines are hazardous relics

Historian Fred Bardelli, of Wallace, maneuvers past the nearly 300-foot-deep shaft at the Evolution Mine site on Tuesday. (Kathy Plonka)Buy a print of this photo

The Evolution Mine triggered gold and silver fever in North Idaho in the 1880s – the first lode-mining site in the mineral-rich Coeur d’Alene Mining District.

Miners pulled ore for decades from the Evolution until it was closed in the late 1940s.

Today, the main shaft of the historic mine outside of Osburn, Idaho, is a forgotten hole: a dangerous and accessible 12-foot-wide puncture in the hillside that drops 300 feet or more into the earth just a short distance from Interstate 90.

“It clearly presents a danger to the public – to hikers and hunters and anyone else who might venture up here,” said Clarence “Butch” Jacobson, a 71-year-old Mullan resident, as he stood at the site last week. He discovered it while visiting 400 abandoned mining sites in North Idaho in the past three years.

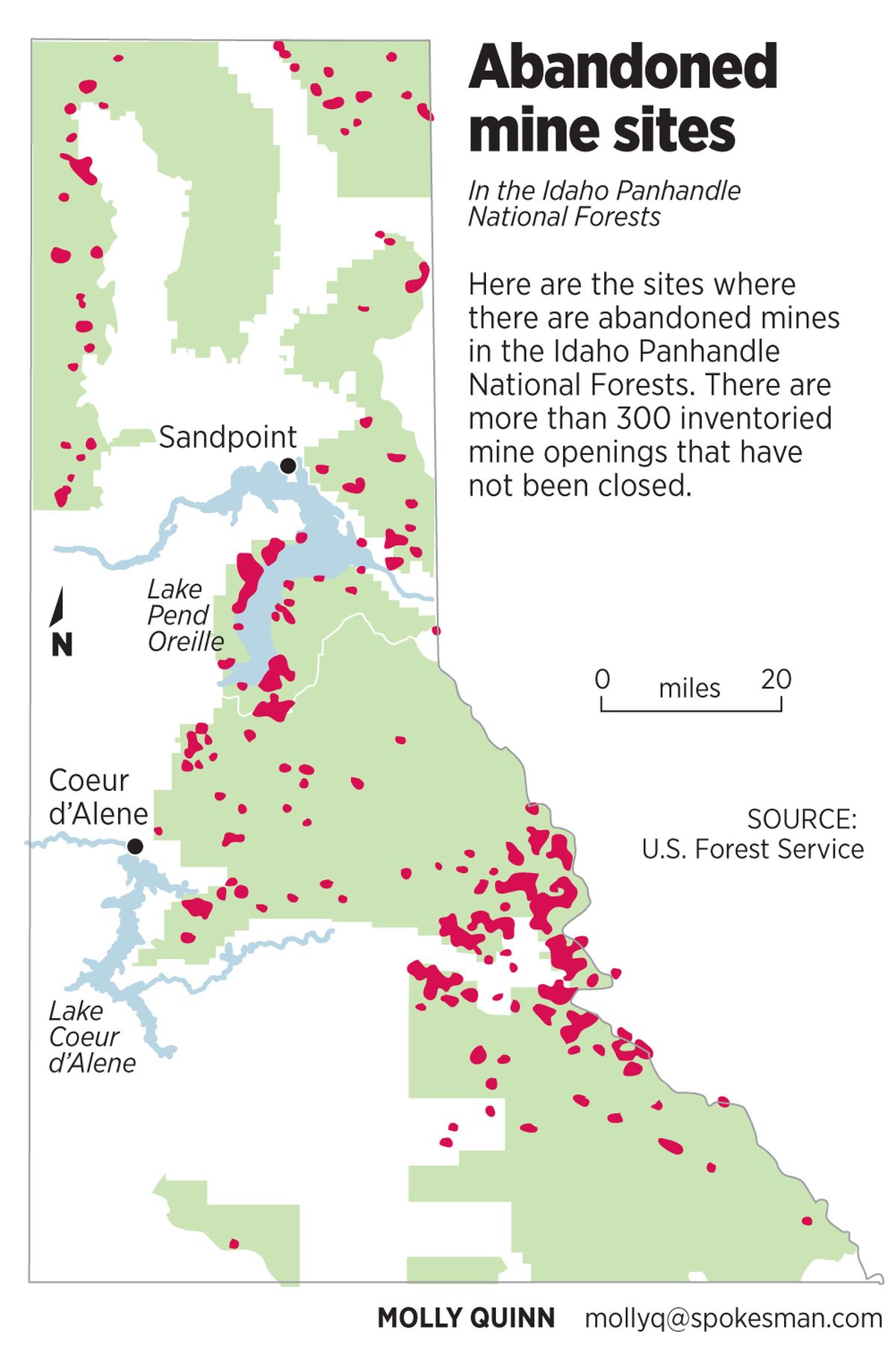

Just on federal land alone, government officials say there are 510 abandoned mine sites in the Idaho Panhandle.

There is no estimate of how many more dangerous sites – like the old Evolution shaft – exist on private property in the region, but they are believed to be numerous.

With the increased popularity of spelunking, caving and geocaching, abandoned mine sites offer a particular attraction along with deadly hazards, experts say.

At least 40 people have died in the past three years in abandoned mines across the United States. The last reported death in this region was in June 1995, when Steve Novak, the son of former Spokane City Manager Terry Novak, was overcome by carbon monoxide and died while exploring an abandoned mine near Lake Pend Oreille.

Two abandoned-mine experts working for the federal government who reviewed photographs of the Evolution shaft said it presents a clear danger, which would prompt them to take immediate action to close it if it were on federal land. Yet federal agencies and local government officials lack authority to order closures of dangerous abandoned mine sites on private property.

The owner of the 20.6-acre patented mining claim promised immediate action on the Evolution.

Dennis O’Brien, an executive with H.F. Magnuson & Co. and an officer of Coeur d’Alene Crescent Mining Co., is listed on public records as the owner and taxpayer. He said he was unaware of the danger.

“I didn’t know there was an open shaft there,” O’Brien said, “and I’ve never been to the site. I’ve been here since 1990 and there’s been no work done there since that time.”

Shown a photo of the shaft opening, O’Brien said: “Yeah, I would say it does present a danger, and we should develop some plan to get it flagged and get it closed as soon as possible.”

“This is an old, inactive mine, and nothing’s been done up there in years,” he said. “We weren’t aware of this hole.” O’Brien later asked for directions so that he and a contractor could visit the site and develop a closure plan.

Jacobson discovered the Evolution site a couple of years ago and revisited it last week with Spokane author and historian Tony Bamonte, who is researching a forthcoming pictorial book on the mining history of the Coeur d’Alenes.

“I just can’t believe that hole is still there, wide open with no protection for people or animals. It’s very dangerous,” Bamonte said as he and three other men – all in their 60s or 70s – walked to the site.

There were no signs, fencing or protective devices.

Fred Bardelli, a retired high school teacher and local historian who also made the trek, said he remembers hearing about the abandoned mine from his late father, World Boxing Hall of Fame slugger Guido “Young Firpo” Bardelli, who would go on to be a legendary contract miner in the area.

“I’ve known about this all my life,” he said. “I remember a house was there when I was a kid in the late ’50s.”

“The way it is now, anybody hunting or walking that ridge, especially at night, there definitely would be a possibility of them falling into that shaft,” Bardelli said.

While Bardelli claimed most longtime residents have known of the Evolution site for years, the current sheriff of Shoshone County said he had no idea the open shaft existed but agreed it poses a danger.

“The issue here is it’s on private property,” Shoshone County Sheriff Mitch Alexander said last week. “Is it dangerous? Yeah, I suppose. Anything can be a risk. Around this county, these kinds of holes are all over.” Alexander said he would contact the property owner.

Bamonte and Jacobson, both with lengthy backgrounds in law enforcement, said they believe an inspection would be essential before closure.

“Who knows what or who may have fallen in that shaft over all these years?” Bamonte said.

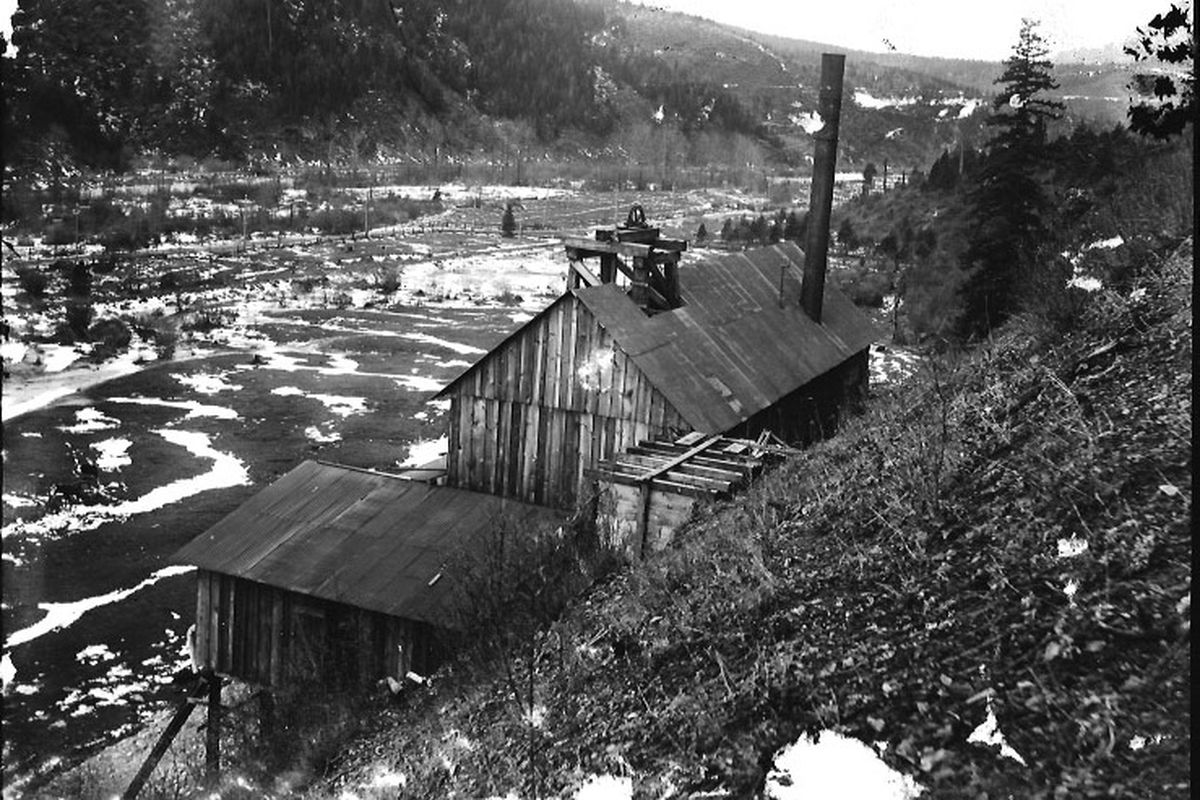

A wood-frame building – about 25 feet by 40 feet with a gallows-frame hoist over the Evolution shaft – was photographed in 1905. But any traces of that structure – except a small concrete footing – disappeared long ago.

When the Evolution Mine was operational, the hoist house covered the shaft where Andrew Prichard is said to have pulled out tons of silver and lead ore.

The wooden structure deteriorated or was torn down and the open hole was left unfilled. About 150 yards to the east of the shaft at a lower elevation is a partially collapsed tunnel, or adit, that’s believed to have connected with the exposed shaft.

An article published in The Spokesman-Review on March 31, 1901, said the Evolution Mine is “commonly known as the oldest claim located in the Coeur d’Alenes,” one staked by Prichard in 1881.

According to historical accounts, before Prichard sank the Evolution shaft, he went north and discovered placer gold on a creek that later would be named after him, prompting a short-lived gold rush in the Coeur d’Alenes.

Many of the miners and mining companies that followed left behind shafts, tunnels and adits that still dot North Idaho. Even in operating mines, shafts posed particular dangers. In his 2003 book, “From Hell to Heaven,” the late Gene Hyde, who spent his career as a mining geologist, documents the deaths of 204 miners killed by falling down mine shafts between 1890 and 1998 in the Coeur d’Alene Mining District.

“We take our abandoned mine lands real seriously up here,” said Kevin Knesek, a forest geologist with the Idaho Panhandle National Forests. Just last week, he conducted an all-staff safety training on the hazards posed by abandoned mines.

“We have identified over 500 shafts, adits and trenches to date on U.S. Forest Service land in the Panhandle, and to date we’ve closed 242 of them,” Knesek said. Closure costs range from $5,000 to $8,000.

“This season we closed three sites, and for next season we’ve identified at least an additional 12,” Knesek said.

Closures are done with “bat gates” – steel mesh covers where bat habitat is identified – or polyurethane foam plugs. In locations where heavy equipment can be used, some sites are backfilled, but the Forest Service does not use explosives to collapse shafts or tunnels, Knesek said.

In some instances, the Forest Service uses a helicopter to drop materials and equipment to close abandoned sites. Where claims still exist, the Forest Service installs hinged, locked gates.

“We try to work with claim holders to mitigate the danger to the public but also allow the claim holder continued access to their claim,” he said.

Knesek said if the Evolution site were on Forest Service land, “then I would call it a ‘hazard’ and seek to mediate that immediately.”

Scott Sanner, a mining engineer with the U.S. Bureau of Land Management, oversees 182 inventoried abandoned mining sites on 242,000 acres of BLM land in the Idaho Panhandle. Of those, 54 have been mitigated or closed off, he said. “We mitigate as time and money allow.”