Journalist Louise Shadduck helped transform Idaho

Louise Shadduck was a well-known Coeur d’Alene author and longtime journalist, but when she died in 2008, her pastor at First Presbyterian Church was stunned when he walked into the church to conduct her funeral.

“The church was full of plainclothes cops,” Mike Bullard recalled, and the front three rows were filled with current and past governors and top state officials. “They’d chartered a plane,” the now-retired pastor said.

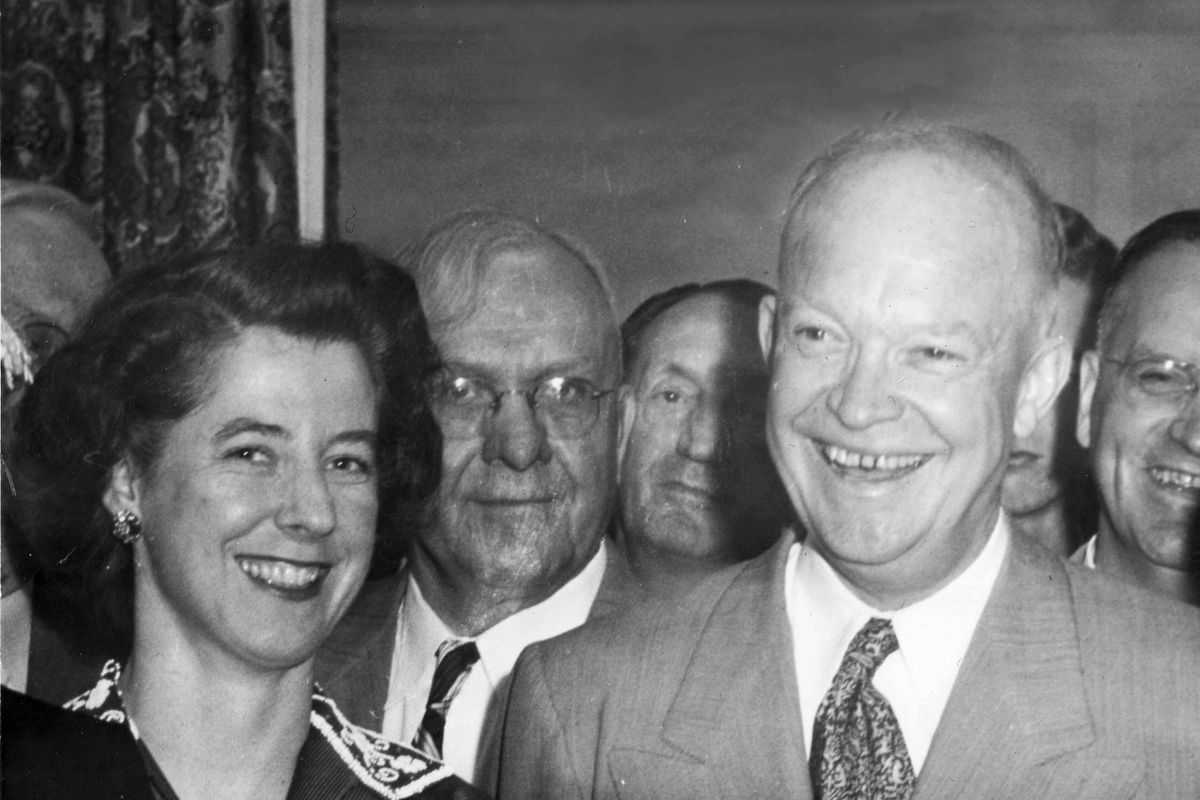

Bullard decided to go through Shadduck’s extensive papers at the University of Idaho to write a biography. There, he found pictures of Shadduck with Presidents Eisenhower, Nixon and Reagan, as well as records of how she changed Idaho and helped both boost the state’s moribund economy and create Farragut State Park.

Shadduck was 93 when she died, and Bullard says few alive today know of her remarkable early career, including her work for two Idaho governors, a U.S. senator and a congressman. Bullard’s book, “Lioness of Idaho: Louise Shadduck and the Power of Polite,” comes out today.

Shadduck, raised with six brothers on a Coeur d’Alene dairy farm, started work as a reporter at the Coeur d’Alene Press fresh out of high school in 1933, when few women followed that course. “She was a pioneer,” Bullard said. After growing up with six brothers, “She knew if she wanted something, she had to stand up for herself,” he said.

Assigned to cover the 1944 Republican National Convention in Chicago, she met other women who were successes in journalism and politics, including newly elected congresswoman Clare Booth Luce. She was soon asked to organize the Kootenai County Young Republicans, and volunteered on the gubernatorial campaign of C.A. “Doc” Robins, whom she had liked since interviewing him seven years earlier.

Robins won and immediately began trying to get Shadduck to come to Boise and work for him; she initially resisted, saying she wanted to remain a reporter, but eventually gave in. She went on to run Robins’ Boise office and then those of an array of top Idaho Republicans.

She worked on Dwight Eisenhower’s campaign for president in 1952 and became well-acquainted with his running mate, Richard Nixon. Four years later, Shadduck gave a speech at the Republican National Convention in San Francisco touting Eisenhower’s re-election bid, drawing national attention.

She also was running her own race that year: She challenged two-term Idaho Democratic Rep. Gracie Pfost, hoping to win the seat back for the GOP. Bullard writes that it was the first time in U.S. history that two women faced each other as the major-party candidates for a seat in Congress.

Shadduck lost and later referred to the run as “a fit of temporary madness.” She said she preferred her behind-the-scenes political work.

But she was soon back in a high-profile role, as the state’s director of commerce and development under Gov. Robert Smylie – another first for a woman, holding an Idaho Cabinet post. Idaho’s economy was in the dumps, and the state had virtually no budget to promote itself to tourists or businesses.

At that time, what’s now Farragut State Park in North Idaho was a wreck of bare foundations where an abandoned naval base had stood, but it was right on Lake Pend Oreille. Smylie wanted it to be a state park, but the state had neither the money for development nor the rights – a deed restriction said the land would revert to the federal government if used for anything other than wildlife management.

Shadduck saw her opening when a major Scouting event was proposed. She managed to get first an international Girl Scout gathering in 1965, then the 1967 Boy Scout World Jamboree, and then the big 1969 National Boy Scout Jamboree held at the site. Each event required vast improvements, from breaking up the old foundations to building arenas, a waterfront and beach. Shadduck recruited the National Guard to do much of the heavy work, and tapped her Washington, D.C., connections to get Navy help and legislative and federal approval.

More than 33,000 Boy Scouts and leaders attended the 1969 event, and astronaut Neil Armstrong, an Eagle Scout, extended them a special greeting from space as the boys watched his moon landing on a giant screen.

Shadduck launched advertising campaigns each time the big events put Idaho in the spotlight, and the state’s economy surged. Tourism alone quadrupled.

She later served as executive director of the Idaho Forest Industries Council for eight years; as president of the National Federation of Press Women, which included speaking engagements around the world; and as chairwoman of major Idaho GOP campaigns, including Ronald Reagan’s in 1980 and Larry Craig’s in 1990.

Shadduck wrote five books, all works of nonfiction, including a history of Coeur d’Alene and a biography of Andy Little, Idaho’s “sheep king.”

The Idaho Department of Lands’ office building in Coeur d’Alene is named for Shadduck, and there’s a bronze bust of her at the Coeur d’Alene library. Her network of friends and acquaintances was legendary, as was her mentoring of young people; she was an early mentor of Idaho Gov. Dirk Kempthorne, whom she met when he was student body president at the University of Idaho.

The book is long on Shadduck’s virtues, and Bullard said he learned much from her example. When people complained about government, Bullard said, “She said the Congress is no better or worse than the people that elect them.”