Gentleman of the House: Former Speaker Tom Foley dies at 84

For 30 years, Tom Foley navigated the politics of the region and the nation in the House of Representatives with a rock-solid sense of dignity and a belief that bringing people together was more productive than letting them tear each other apart.

Foley, the Spokane native who rose to be House speaker, died Friday at 84 from complications of a stroke. He was described by both Democrats and Republicans with a word that might not show up on many of today’s political resumes: statesman.

“He was always dignified,” said George Nethercutt, the Republican who ousted Foley in 1994 after 15 terms in the House. But Foley bore him no ill will, and complimented Nethercutt in a post-election lunch. “I think we’ve lost a lot of that dignity and respect and attitude,” Nethercutt said.

Foley represented Eastern Washington’s 5th Congressional District for 30 years, the last five as speaker, before losing both jobs in that historic electoral defeat. He went on to serve as U.S. ambassador to Japan for President Bill Clinton from 1997 through 2001, was a presidential adviser on foreign policy matters, a principal at a high-powered Washington, D.C., law firm and a board member for many organizations.

He died Friday at 9:13 Eastern time in Washington, D.C., according to his wife, Heather Foley.

Tall and in his later years silver-haired, Foley looked like a congressman ordered up from Hollywood central casting, but he worked his way up through the ranks of the House.

His father, Ralph Foley, was former county prosecutor and longtime Spokane County Superior Court judge. His mother, Helen Higgins Foley, was the daughter of a railroad worker. He grew up in a Democratic household on Spokane’s rock-ribbed Republican South Hill.

He was a young deputy Spokane County prosecutor and assistant attorney general before going to Washington, D.C., as an aide to Sen. Henry “Scoop” Jackson in the early 1960s. He ran against a well-established Republican incumbent, Walt Horan, in 1964.

Foley often told the story of his entry into that race, on the last day of filing week. He had asked longtime Democratic leader Joe Drumheller whether he’d be willing to support him if he ran against Horan in two years, 1966, when it was assumed Horan would retire. Drumheller fumed against young politicians who were always putting things off, adding that he’d back Foley that year but not two years hence. Foley thought it over, wired his resignation to Jackson, and got in a car with a couple of friends to drive to Olympia, where his paperwork had to be filed by 5 p.m. that day.

They arrived in Olympia and ran out of gas. Foley had to run to the secretary of state’s office, arriving minutes before closing time.

Senior U.S. District Judge Justin “Bud” Quackenbush, a lifelong friend and the manager of Foley’s early campaigns, still laughs about that close call, saying Spokane’s most accomplished congressman almost didn’t make it onto his first ballot.

Foley beat Horan that year in a race that became legendary for its civility, then fended off challengers for the next 14 election cycles. A skilled debater at what is now Gonzaga Prep, Foley insisted that an incumbent always had an obligation to debate an opponent; although some chose not to, others took him up on that, and a campaign could feature as many as a dozen debates.

In 1968, Foley married Heather Strachan, whom he’d met when both worked on Jackson’s staff in the early ’60s. She’s a member of the bar, but served for many years as his unpaid chief of staff in the congressional office. The couple had no children, and regarded many members of their office staff as extended family.

“He taught us that public service really was a high calling and an honorable profession,” said former aide Todd Woodard, who now works for Spokane International Airport. “That’s probably the life lesson the judge brought home around his family’s kitchen table, and hopefully I bring that home as well.”

The 5th Congressional District is a mix of wheat farms, timberland, federal dams, Indian reservations and small towns, with more than half of the voters living in Foley’s hometown of Spokane.

Some of his elections were squeakers, but many were blowouts against weak opposition.

Between elections, he rose steadily in the ranks of House Democrats, first as chairman of the Agriculture Committee, then House whip, then House majority leader. He ran unopposed, said former Rep. Norm Dicks, a longtime friend and ally, because other Democrats respected him and sought him out for those jobs. He also got along with his GOP counterparts like House Minority Leader Bob Michel of Illinois.

“They got along famously,” Dicks said. “They were both people who knew how to get things done.”

Foley served on the Iran-Contra investigation committee, where he was recognized as a calming influence during the scandal. He helped lift a ban on saccharine that the Food and Drug Administration was leveling against the artificial sweetener. He helped reshape farm programs and food stamps.

In June 1989, when Jim Wright was forced to step down, Foley was elected House speaker, the first person to serve as constitutional leader of the House from any place west of Texas.

He managed to quiet some of the partisan rancor that erupted in the House over Wright’s forced retirement, and later that year he invited then-President George H.W. Bush to Spokane for a bit of bipartisan showmanship that involved dinner at a Browne’s Addition restaurant and planting a White House elm sapling in Riverfront Park.

Although Foley was often in the middle of national and international events, he was schooled by his mentors, Sens. Henry Jackson and Warren Magnuson, in the importance of delivering services to local constituents. Northwest issues were more important to him than partisan issues, and the Washington delegation always pulled together regardless of party lines, said former Rep. Sid Morrison, a Zillah Republican. “He remembered so well where he came from.”

One person’s pork, Foley used to say, was another person’s wise investment in the local infrastructure. With him in powerful positions in Congress, Eastern Washington’s infrastructure got repeated investments: Fairchild Air Force Base began its transformation from a World War II-era depot to one of the military’s largest and most modern tanker bases. Highway 395 from Ritzville to the Tri-Cities went from a winding road to a four-lane highway. Gonzaga University, which Foley attended, got a new library, which the school named for his parents. Spokane got a paved walking and biking path to Coeur d’Alene to mark the state’s centennial. SIRTI got an infusion of federal cash to get off the ground.

In 1994, that federal spending worked against him as Nethercutt ran against what he called bloated government and entrenched incumbents. Foley had challenged a state initiative that limited House terms to six years; months after the election, the U.S. Supreme Court agreed with him that term limits were unconstitutional.

And he’d angered the National Rifle Association – a decadeslong supporter – by allowing the House to vote on and pass a ban on some military-style semi-automatic rifles. For the first time since the start of the Civil War, a sitting House speaker lost a bid for re-election.

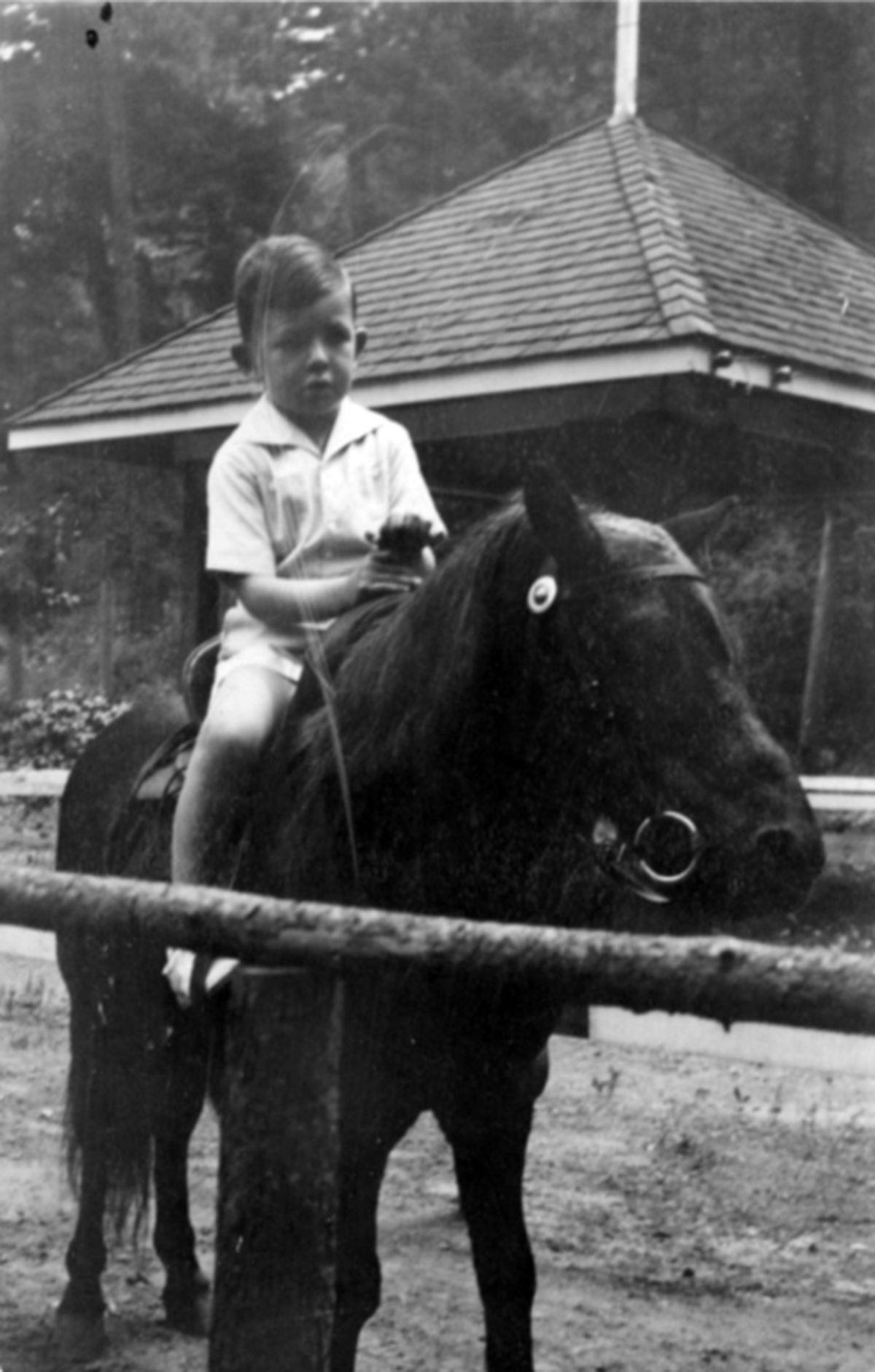

A strong orator with the gift of a good memory for complicated facts, Foley was probably at his best when telling stories, many of which had him as the butt of the joke. He often told of attending the Omak Stampede and making a fool of himself on a horse, which prompted the announcer to say “our good congressman is not wasting his time in D.C. on riding lessons.” He was mortified, but an aide assured him that was perfect – there was nothing locals hated more than a city slicker showing off on a horse. After that he usually carried Omak as long as it was in his district.

Or the time he was paged as a young congressman at National Airport, for a call from President Lyndon Johnson. Shown into a private room by awed airline staff, he picked up the phone to have LBJ say “John?” No, Mr. President, he replied, this is Tom Foley of Washington. Johnson swore, said he’d told the operator to get him John Fogarty of Rhode Island, and slammed down the phone. Crestfallen, Foley went back to the gate, where an agent asked if he’d been connected to the president. He figured he could truthfully say yes, and was immediately put in first class for the flight home. “I learned then something of the power of the president: Even a wrong number can get you an upgrade.”

Foley had a fondness for electronic gadgets, from cellphones to stereo equipment. He was seldom seen in public without a suit and tie, whether it was a luncheon speech, a campaign stop or a fact-finding mission to Grenada after the U.S. military incursion. Asked why, he said once that it is what people expect their congressman to look like. Watching a retrospective of his career shortly after becoming speaker, he was shocked at his weight gain over the years, went on a strict diet, and began pumping iron and riding a bicycle to shed pounds.

After serving as ambassador to Japan, Foley worked for several years at Akin, Gump, Strauss, a Washington, D.C., law and lobbying firm. He retired in 2008 and had been in fragile health after hip and knee replacements and Bell’s palsy. He had been under hospice care for several months and suffering from recurring bouts of aspiration pneumonia.

He is survived by his wife of nearly 45 years, Heather; his sister Maureen Latimer and her husband, Richard, in Santa Rosa, Calif., three nieces and two nephews.

Services are pending for St. Aloysius Church at Gonzaga University, and in Washington, D.C. In lieu of flowers, the family suggests donations to the Foley Institute for Public Policy & Public Service at Washington State University.