Parents concerned about candylike pill packaging

It’s a lesson parents often tell their children: Medicine is not candy.

That’s why Nicole Ingram was so surprised when her daughter came home from a day at a Coeur d’Alene community center with a packet of Mike and Ike candies designed to look like prescription medication.

“I grabbed it and I was like, ‘Oh my gosh, you’re kidding me, this can’t be real,’ ” Ingram said.

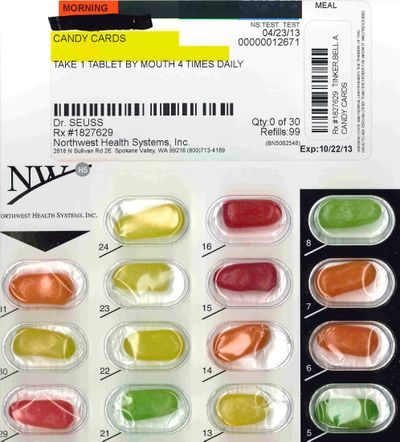

With a prescription label at the top – the patient is listed as Tinkerbell and Dr. Seuss the prescriber – the foil-backed cards look nearly identical to prescription medication.

She tracked the product to Northwest Health Services, a Spokane pharmacy that distributes to long-term care facilities and had a booth at a senior citizen health fair at the Kroc Center, where her kids attend several times a week.

The pharmacy defends its use of the candy display, citing widespread industry practices, despite poison control recommendations that candy and medicine should never go together.

After concerned parents contacted the Kroc Center, its management issued a statement saying, “Any materials distributed at the event were at the vendor’s discretion and were not designed or intended for children.”

The pharmacy said the candies are only used for training purposes and trade shows and are not marketed for children.

In an email response to the concerned parents, the pharmacy apologized for allowing the children access to the candy without their parents’ permission and pledged to work to ensure it doesn’t happen again.

The company has since ceased using Disney character names on the candy, but insists the cards have a purpose and that the chances of children getting them are low.

“It’s a very specific population that’s receiving this packaging type, and they’re usually in a facility,” said Northwest Health Services Director of Pharmacy Garth Fritel.

He said nursing homes and other facilities order the candy medicine when they hire new employees. They use the fake prescriptions to train the new employees how to handle medication and sort it for each patient. They are then supposed to lock any remaining packets away in secure medicine carts.

Fritel said the practice of using candy instead of medicine is common.

Samantha Timmermann, marketing director for Pharmacy Development Services, a national pharmacy marketing company, said there is no guideline that says pharmacies can’t use candy medicine in marketing efforts. She said she often sees candy used for training purposes, but when it comes to handing candy medicine out to the public, it’s up to each pharmacy to make a judgment call.

“My advice with the pharmacy owners is to use precaution in their demographic,” Timmermann said.

Poison control representatives have more clear-cut guidelines.

“We suggest that you never, ever, regardless of who you are, imply that a candy could be a medication,” said Katie Von Derau, a call room supervisor for the Seattle-based Washington Poison Center who is also a pediatric nurse.

Of the calls made last year to the poison control center involving children under 6 years old, 48 percent of the poisonings involved medications. Von Derau said it’s because kids can’t tell the difference between medicine and candy. Any implication that one is the same as the other is dangerous, she said.

“If they see something one time, and in this case it would be candy in this pack, they may then later associate seeing the same thing as being candy when it’s not,” Von Derau said.

According to Safe Kids Worldwide, which works to prevent childhood injuries, one-third of all child poisoning emergency room visits in 2011 were from their grandparents’ prescriptions.

Ingram, whose daughter brought home the candy, said the risk that any child might come into contact with the fake medicines and later confuse real pills for candy should be enough to deter anyone from making the candy versions.

“No matter what they were using it for, candy and drugs, you would just think never go hand in hand,” she said.