Jail policy on prescription meds can leave care gaps

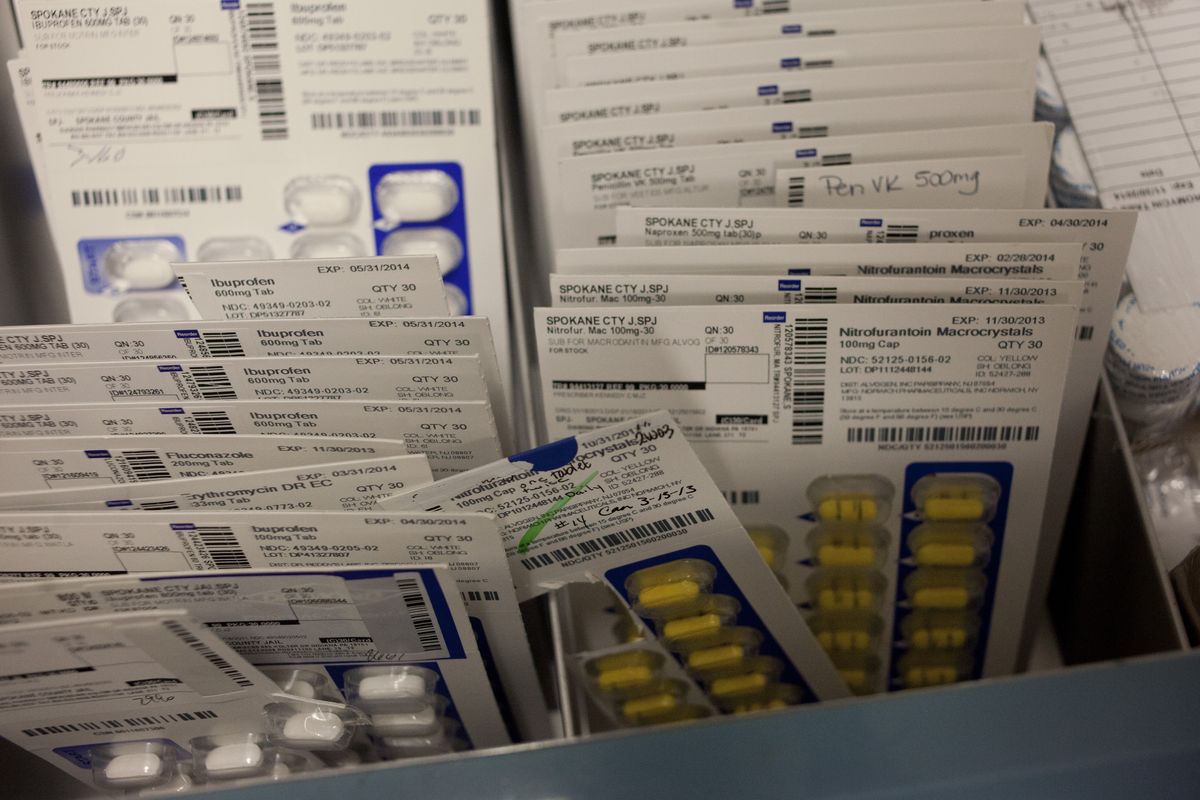

Spokane County spent about $60,000 a month last year doling out prescription medicine to inmates at Geiger Corrections Center and the Spokane County Jail.

Ninety percent of the prescriptions were ones the inmates were given before they even reported to jail, so it might sound easy to cut that cost by allowing inmates to bring their medications with them. Think of it: Costs to buy new meds would plummet, inmates who need medications immediately would always get them and complaints about poor medical care would drop.

But it’s not that easy.

Once someone is in custody, the county assumes liability for the safety of the inmate who’s taking the prescription as well as fellow inmates who might look to buy drugs off that person.

If the medicine is tainted in any way, it could be dangerous for whoever ingests it and the liability risk for the jail soars.

That’s why Spokane County’s practice, in alliance with corrections facility norms, is to not allow outside drugs inside the jail.

Cheryl Slagle, the jail’s nurse manager, said family members still show up to the jail daily with medications for inmates. They’re turned away every time, although the nurses will copy information off the medicine containers to help them replace the prescriptions.

“We can’t dispense it,” Slagle said of the medicines. “We can’t identify what’s in there, and we can’t be certain that what’s in there hasn’t been tampered with in any way.”

The official policy, written in 1995, allowed drugs to be brought into the jail and dispensed if the jail physician reviewed them.

About five years ago, however, the nurses union objected to having nurses comb through pills, said jail Cmdr. John McGrath; the formal policy was not revised, but practices changed.

Now, some inmates and their families question whether these costly security precautions end up preventing those who need medications right away from getting them.

Complaints, mostly in the form of jail grievances but a few that have amounted to lawsuits that were later dismissed, have come from inmates who say they have gone days, sometimes even weeks, at the beginning of their jail stays deprived of their medication.

One AIDS patient who spent weeks in the jail last year was eventually released while he awaited trial because the jail couldn’t meet his medical needs, according to court records. His attorney argued in court several times that his client wasn’t getting proper medications or nutrition.

Another complaint, from a father on behalf of his son, is currently under investigation. The father accused the jail of waiting weeks to give his son the proper psychiatric drugs, resulting in manic depressive behavior and his son being put on suicide watch.

Some of the complaints, Slagle said, involve inmates who believe they should be on narcotics, or who have other disagreements with the jail’s staff doctor about what drugs are necessary. Others are a matter of not being able to quickly get medical records, leaving patients without their prescriptions in the meantime.

The jail stocks some drugs, such as blood thinners and insulin. But more often than not there’s a delay providing inmates with medications to treat mental illness – the drugs that could prevent inmates from becoming violent toward themselves or others.

Both public defenders and jail administrators acknowledge that the system fails some inmates. The question is who, if anyone, is to blame.

John Rodgers, director of the Spokane County Public Defender office, said he gets complaints regularly from inmates who do not think their care is adequate. It can be hard to identify those who are really in need of more care versus those who have unrealistic expectations or are drug-seeking, he said. But it’s “heart-wrenching” when a diabetic doesn’t get his or her insulin or those with a disease like schizophrenia can’t take the medications that keep themselves and everyone around them safe, he said.

“I really think the jail does give a damn about that,” Rodgers said. “I really think they do. But they’re up against inmates that might hoard or abuse or trade or whatever.”

Spokane civil rights attorney Jeffry Finer called the delays “a very large problem.”

“When you show up (to jail), your medical history’s not coming with you,” Finer said.

It’s not a new problem. But with the county commissioners taking over control of the jail starting last month, it’s one that’s likely to be revisited in the near future.

Meds ordered from Pennsylvania

Every inmate brought to the jail is interviewed about medical care on arrival.

Slagle, the nurse manager, said the questions asked include whether they are on medications, if they have pre-existing conditions and whether they need immediate treatment.

Slagle said some inmates know exactly what medications they’re taking and others just know it’s “the little yellow pill.”

Then there are the seasoned criminals who are seeking drugs with no real medical need.

“They know all the lingo, they know what meds they want when they come in,” Slagle said. “So they sound very convincing, and then turns out they weren’t on any of those medications.”

The inmates are given a form to sign that authorizes their primary care physician or the staff at the last place they received medical care to release the records.

After they sign the waiver, it’s faxed to their medical provider.

Jail Cmdr. McGrath said a response can take a while.

“The delay really comes from when we get the information back from the third-party provider,” McGrath said.

With medical offices closed on weekends and doctors not always returning phone calls the same day, patients can go days without the jail getting their records and being able to give them their medications. Slagle said information is easier to obtain from the local hospitals since their records departments work 24 hours a day.

Emergency prescriptions, like diabetic medications or blood thinners, can be prescribed by the jail doctor and administered more quickly.

Even when someone does have a legitimate prescription, the jail doctor still gets the final say on what drugs inmates get while in jail.

Slagle said the doctor will occasionally use the opportunity to force someone who might be on the wrong medication, or mixing medications with heroin or methamphetamines, to detox and find a new regimen that works.

If the doctor allows the inmate to have a prescription, new drugs are ordered from the county’s pharmaceutical distributor, located in Pennsylvania.

McGrath said the county takes new bids for pharmacy suppliers every year, and every year the pharmacy 2,000 miles away is the cheapest. The drugs – which are always generic forms of the medication unless the inmate has a proven history of an adverse reaction and requires the more expensive name brand – take about 24 hours to reach the jail after they are ordered.

Slagle said that in emergencies deputies have run to a local pharmacy to pick up prescriptions. The 24-hour gap also can be filled with stock medication, but the majority of the inmates have to wait.

Finer, the civil rights attorney, said the holes in the system are not necessarily deliberate.

“It is probably more a financial problem for the jail than it is intentionally not giving people their medications,” Finer said.

That financial squeeze extends to staff.

The jail isn’t staffed by a doctor around the clock. There is no staff psychiatrist, although there is one on call. There’s also no pharmacist who could inspect pills brought into the jail.

With the revolving-door nature of a county jail, there’s no way to anticipate every kind of drug that would be necessary to have on hand. And aside from those who self-report, the jail doesn’t have any warning when someone with a serious medical condition is coming to jail.

Sheriff Ozzie Knezovich said that with the state cutting funding for mental health services, inmates who should be at Eastern State Hospital are often kept in the jail. While the jail is equipped with a mental health floor, the arrangement passes the costs of caring for the mentally ill from the state to the local level.

As the only county in the state that has a licensed mental health facility in its downtown jail, about half of all prescriptions purchased there are psychotropic drugs.

At the state level, Department of Corrections Assistant Secretary for Health Services Kevin Bovenkamp said inmates are also not allowed to bring their own medications with them. It’s rarely an issue, however, as most people only have a 30-day supply of their drugs and are in prison for at least a year. Prisons also usually have a heads-up about what inmates are coming and can get their medical records more quickly. The prison system also has a co-pay system of a few dollars for each prescription, something Slagle said the county is working on instating.

Lawyers, doctors and inmates all could take more action

County Commissioner Todd Mielke said the county will be working to find ways to speed up the prescription drug administration process.

Basic steps, he said, could include encouraging inmates to sign the medical release papers as soon as they enter the facility.

Help from the medical community is also needed.

“We have a heck of a time getting medical providers to return our phone calls,” Mielke said. “It is common to go two, three, four days before we get call-backs.”

Nurse manager Slagle said attorneys who know their client is going to jail could also help by calling the jail a week or two ahead of time to notify the staff and getting their clients’ medical records faxed over beforehand to eliminate delays in medical care.

Mielke said the jail’s website may be edited to better explain the county’s prescription drug policies.

A new software system within the jail is set to go online next month that will create an electronic database of each inmate’s medical history.

“That will help us be able to track the needs of each of our inmates in our custody,” Mielke said.

Future commissioner discussions, Mielke said, will include whether the county should switch to a local pharmacy or have a county jail pharmacy.

“I think the biggest issue is that you have a number of people involved with the process,” each acting autonomously, the commissioner said.

Slagle said that with 21,000 inmates a year, it’s easy for one or two to experience a delay in receiving medication.

Inmates can help themselves by using advocates on the outside like lawyers and family members and filing grievances when they believe they are not getting proper care.

When that happens, “you’re grateful that they actually stood up for themselves,” she said.